New research underscores the close relationship between dust plumes transported from the Sahara Desert in Africa and rainfall from tropical cyclones along the U.S. Gulf Coast and Florida.

Giant plumes of Sahara Desert dust that gust across the Atlantic can suppress hurricane formation over the ocean and affect weather in North America.

But thick dust plumes can also lead to heavier rainfall – and potentially more destruction – from landfalling storms, according to a study in Science Advances. The research shows a previously unknown relationship between hurricane rainfall and Saharan dust plumes.

“Surprisingly, the leading factor controlling hurricane precipitation is not, as traditionally thought, sea surface temperature or humidity in the atmosphere. Instead, it’s Sahara dust,” said the corresponding author Yuan Wang, an assistant professor of Earth system science at the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

Previous studies have found that Saharan dust transport may decline dramatically in the coming decades and hurricane rainfall will likely increase due to human-caused climate change.

However, uncertainty remains around the questions of how climate change will affect outflows of dust from the Sahara and how much more rainfall we should expect from future hurricanes. Additional questions surround the complex relationships among Saharan dust, ocean temperatures, and hurricane formation, intensity, and precipitation. Filling in the gaps will be critical to anticipating and mitigating the impacts of climate change.

“Hurricanes are among the most destructive weather phenomena on Earth,” said Wang. Even relatively weak hurricanes can produce heavy rains and flooding hundreds of miles inland. “For conventional weather predictions, especially hurricane predictions, I don’t think dust has received sufficient attention to this point.”

Competing effects

Dust can have competing effects on tropical cyclones, which are classified as hurricanes in the North Atlantic, central North Pacific, and eastern North Pacific when maximum sustained wind speeds reach 74 miles per hour or higher.

“A dust particle can make ice clouds form more efficiently in the core of the hurricane, which can produce more precipitation,” Wang explained, referring to this effect as microphysical enhancement. Dust can also block solar radiation and cool sea surface temperatures around a storm’s core, which weakens the tropical cyclone.

Wang and colleagues set out to first develop a machine learning model capable of predicting hurricane rainfall, and then identify the underlying mathematical and physical relationships.

The researchers used 19 years of meteorological data and hourly satellite precipitation observations to predict rainfall from individual hurricanes.

The results show a key predictor of rainfall is dust optical depth, a measure of how much light filters through a dusty plume. They revealed a boomerang-shaped relationship in which rainfall increases with dust optical depths between 0.03 and 0.06, and sharply decreases thereafter. In other words, at high concentrations, dust shifts from boosting to suppressing rainfall.

“Normally, when dust loading is low, the microphysical enhancement effect is more pronounced. If dust loading is high, it can more efficiently shield [the ocean] surface from sunlight, and what we call the ‘radiative suppression effect’ will be dominant,” Wang said.

***

Additional authors are affiliated with Western Michigan University, Purdue University, University of Utah, and California Institute of Technology.

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation.

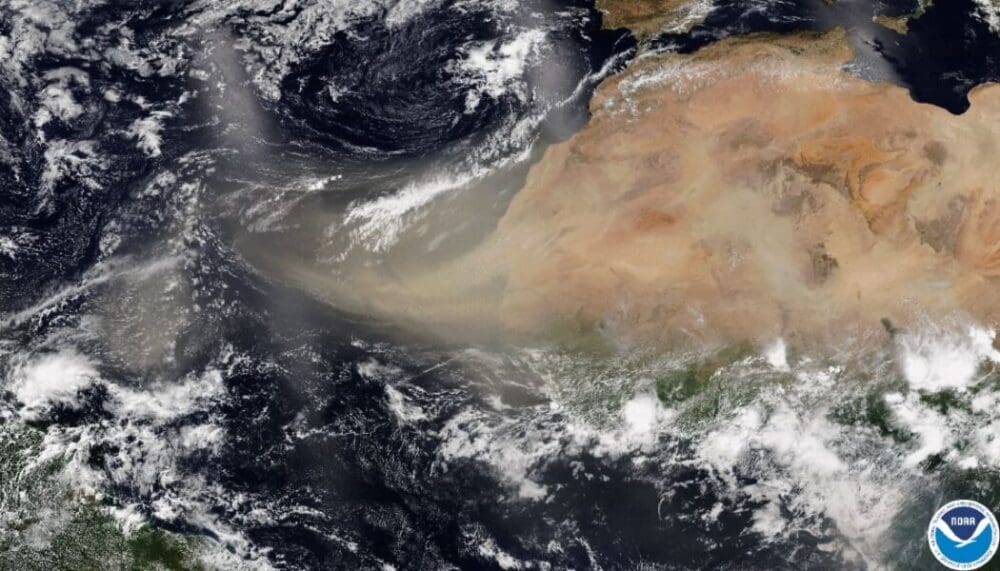

More information: Laiyin Zhu et al. ‘Leading role of Saharan dust on tropical cyclone rainfall in the Atlantic Basin’, Science Advances (10, eadn6106; 2024); DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adn6106 | SU Press Release/Material. Featured image: On June 16, 2020, the GOES-East satellite captured this GeoColor imagery of an expansive plume of dust from the Sahara Desert traveling westward across the Atlantic Ocean. Credit: NOAA