Oslo, Norway | AFP

Supporters see deep-sea mining as a boon for the green energy transition, while opponents see it as an irresponsible gamble.

It is not yet a commercial reality, but that could change in 2025 as Canadian company The Metals Company has applied for mining permits in the United States.

Here are some key things to know about deep-sea mining:

What resources lie on the ocean floor?

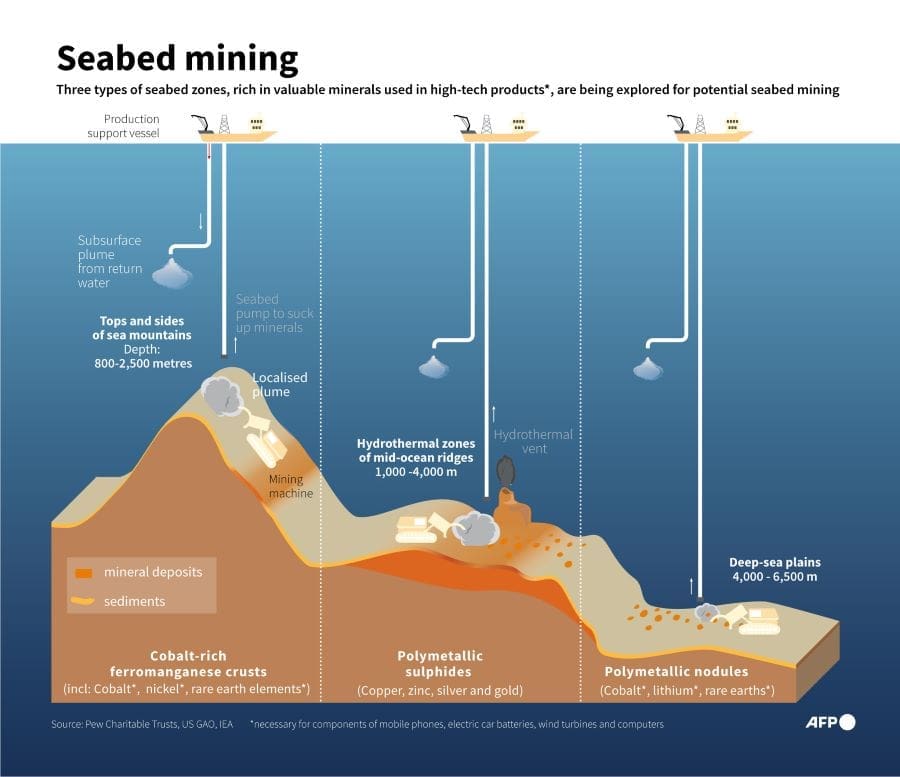

The seabed is home to three types of metal deposits that have taken thousands or even millions of years to develop.

Polymetallic nodules are potato-sized pebbles that result from the very slow precipitation of minerals around fragments such as shark teeth or fish ear bones.

Found at depths of 4,000 to 6,000 metres (13,000 to 20,000 feet), particularly in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and Mexico, these nodules contain mainly manganese, iron, cobalt, copper and nickel.

Cobalt crusts are rocky masses found at depths of 400 to 4,000 metres, formed by the accumulation of metals contained in seawater. They have to be laboriously separated and removed from the underlying rocks, with one area explored in the northwestern Pacific. They contain manganese, iron, cobalt, and platinum.

Sulfide deposits or polymetallic sulfides are metal-rich deposits (containing copper, zinc, gold, silver) around chimneys from which water enriched with dissolved metals is expelled. These clusters are found at depths of between 800 and 5,000 metres, at ridges or near submarine volcanoes in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

Why mine them?

Cobalt and nickel are essential elements used in electric car batteries. They are currently extracted from minerals mined on land at great human and environmental expense, in addition to the substantial and toxic waste from the chemicals-based refining process.

Electric cables are made of copper and demand is expected to skyrocket in line with electrification in the 21st century.

Supporters of deep-sea mining argue that collecting nodules on the Pacific floor does not mean razing or reducing the seabed’s rocks and mountains to dust, as is done at mines on land.

The environmental cost?

Little is known about deep-sea environments, which play a role in storing carbon and have long been free from human activity.

Scientists and environmentalists fear that mining activities risk disturbing or destroying marine ecosystems about which very little is known.

According to the international scientists’ initiative Ocean Census, only 250,000 species, out of the two million believed to populate the oceans, have been identified.

Mining activities could destroy the habitats of organisms living on or near the seabed; alter the water’s local chemistry; cause noise and light pollution; or result in chemical leaks from machinery and equipment, Greenpeace fears.

32 states, including Brazil, Britain, Canada, Germany and Mexico, have called for a moratorium on deep-sea mining in international waters, according to the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition.

Current state of play?

No commercial production licence has been issued anywhere in the world for deep-sea mining, though some countries have launched or are preparing to launch exploration in their exclusive economic zones (within 200 nautical miles, or 370 kilometres, of their coastlines).

The only industrial technology developed so far is that to retrieve nodules.

Japan has two exploration contracts, while the Cook Islands has awarded exploration licences to three companies in their waters and is also cooperating with China — which is very active in the sector.

In Europe, Norway had planned to award exploration licences for deep-sea mining in 2025, a move delayed until 2026 as part of a political compromise.

In international waters, it is the International Seabed Authority (ISA) that authorises deep-sea mining. It has awarded exploration licences to several companies and countries to test their technologies, but none so far for actual mining.

Torn between proponents of mining and advocates of a moratorium, the ISA is struggling to produce a “mining code” that has been under negotiation since 2014.

Canada’s The Metals Company lost patience and on Tuesday applied for a commercial mining licence in the Clarion-Clipperton zone in the United States, bypassing the ISA, to which the country is not a party.

US President Donald Trump has issued an executive order opening up the possibility of unilaterally authorising companies to mine nodules outside US waters, in international waters.

phy/po/jll/giv

© Agence France-Presse

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by AFP

Featured image credit: Wikimedia | CC BY-SA 4.0