Summary:

Extreme weather has long been known to damage infrastructure and displace communities, but new research shows it also disrupts education on a scale that has gone largely unnoticed.

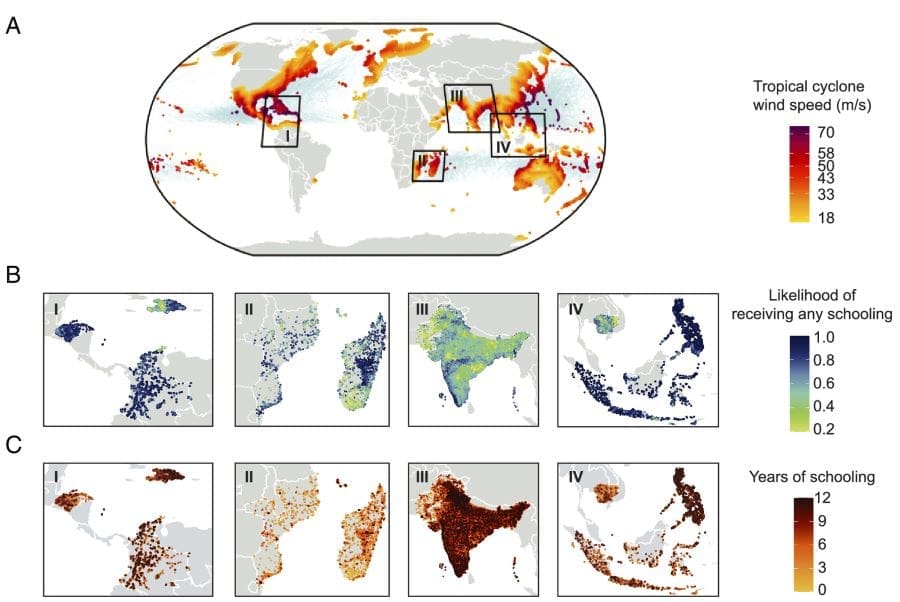

A study led by Stanford researchers finds that tropical cyclones significantly reduce school attendance among children in low- and middle-income countries, especially girls and those living in areas unaccustomed to frequent storms. The research, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, analyzed data from over 5.4 million individuals across 13 countries exposed to cyclones between 1954 and 2010. It found that children who experienced a cyclone during preschool age were more likely never to attend school, with effects as high as an 8.8% increased likelihood of no schooling in regions with limited prior exposure to storms.

From 2000 to 2020, the study estimates, tropical cyclones prevented more than 79,000 children from starting school and led to a total loss of 1.1 million years of education. Girls were disproportionately affected, likely due to social and economic pressures following disasters. The findings draw attention to an overlooked consequence of climate change and call for targeted interventions to protect education systems in vulnerable regions as storms intensify globally.

Missed school is an overlooked consequence of climate change

New Stanford-led research sheds light on an overlooked climate consequence: the impact of tropical cyclones on schooling opportunities and education in low- and middle-income countries. The study reveals how children in the path of hurricanes are set back in their schooling, particularly in areas unaccustomed to frequent storms, with girls shouldering an uneven share of the burden.

The findings identify a new pathway by hurricanes and tropical storms – which together are called “tropical cyclones” – get in the way of social development. It also identifies where and to whom efforts should be directed to mitigate those harms.

“There’s a sweet spot – or maybe I should say a sour spot – where cyclones are intense enough but also rare enough to wreak havoc that causes children to lose out on the opportunity to attend school,” said study senior author Eran Bendavid, a professor of medicine and health policy in the Stanford School of Medicine and a senior fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

A growing threat to education

Tropical cyclones are rotating systems of clouds and thunderstorms that produce strong winds and heavy rain. Estimates of impacts of tropical cyclones are often regional rather than global and do not consider population vulnerabilities.

As the climate continues to warm, the frequency of stronger tropical cyclones is expected to rise, amplifying their already significant impact on vulnerable populations. These powerful storms can damage school buildings and roads leading to them, as well as dwellings, displacing children or making it necessary for them to help out with home repairs.

The research team analyzed schooling records of over 5.4 million people across 13 low- and middle-income countries hit by tropical cyclones between 1954 and 2010. The findings are stark: exposure to any cyclone at preschool age (around 5 or 6 years old) is associated with a 2.5% decrease in the likelihood of starting primary school, and as much as an 8.8% decrease after intense storms in communities less accustomed to such events.

In the past 20 years, tropical cyclones have prevented more than 79,000 children in the study’s 13 low- and middle-income countries from ever starting school, according to the study. Across all affected students, these storms have resulted in a total loss of 1.1 million years of school.

The findings show that girls are disproportionately affected. This gender disparity further exacerbates educational disparities in low- and middle-income countries, and may reflect mechanisms such as being kept away from school to help with household needs in the wake of a storm.

Communities with low schooling rates, where education is often given less priority, also suffer more. In these areas, the study found significant decreases in enrollment, further widening the gap in educational attainment between populations where education is prioritized and those where it is not.

“Education is key to personal development, but tropical cyclones are depriving vulnerable populations of the opportunity to go to school,” said study lead author Renzhi Jing, a postdoctoral scholar in the Stanford School of Medicine and an affiliated researcher at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

Consequences and solutions

Children who were exposed to tropical cyclones are less likely to complete primary school, enroll in secondary school, and are more likely to experience reduced years of schooling, the researchers point out. This not only limits their future economic opportunities but also perpetuates cycles of poverty and inequality in regions already struggling with these issues.

Interestingly, the study revealed that regions more frequently exposed to tropical cyclones tend to have smaller declines in school enrollment. This suggests that communities with regular cyclone exposure may have developed some level of adaptation, whether through improved infrastructure, better preparedness, or more resilient social systems. However, in regions where cyclones are rare, the lack of such adaptive measures makes the impact of these storms much more severe, highlighting the need for targeted disaster risk reduction and adaptation strategies.

The study’s findings underscore the urgent need to address the educational impacts of climate change, particularly in the world’s poorest regions. As the frequency and severity of tropical cyclones increase, so too will the number of children whose education is disrupted. Policymakers and international organizations need to prioritize the protection of educational infrastructure and support systems, particularly for girls, according to the study’s authors.

Journal Reference:

R. Jing, S. Heft-Neal, Z. Wang, J. Chen, M. Qiu, I.M. Opper, Z. Wagner & E. Bendavid, ‘Decreased likelihood of schooling as a consequence of tropical cyclones: Evidence from 13 low- and middle-income countries’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 122 (18) e2413962122 (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2413962122

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Rob Jordan | Stanford University

Featured image credit: Tri Le | Pixabay