Summary:

The world’s oceans are heating at an accelerating pace — but not evenly. A new study reveals that two distinct bands circling the globe near 40 degrees latitude are warming faster than anywhere else on Earth. The first band, located between 40° and 45° south, shows the strongest warming trend, especially in waters near New Zealand, Tasmania, and east of Argentina. A similar zone near 40° north is heating rapidly as well, with pronounced effects in the North Atlantic east of the United States and the North Pacific near Japan.

According to lead author Dr. Kevin Trenberth, this pattern has emerged since 2005 and is linked to poleward shifts in jet streams and ocean currents that redistribute excess heat from greenhouse gas-driven global warming.

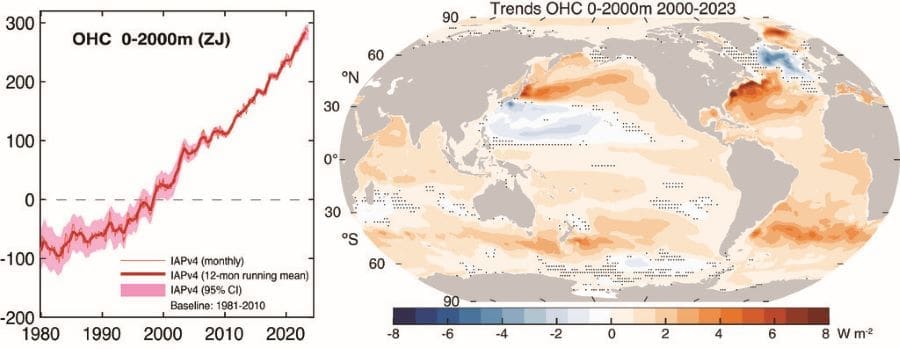

The researchers processed a massive dataset spanning atmospheric and oceanic conditions from 2000 to 2023, analyzing ocean temperatures down to 2,000 meters in 1° latitude bands. They observed strong heat accumulation in these two zones, in contrast to an unexpected absence of warming in the subtropics near 20° latitude. While some of the variation is likely due to natural phenomena like the El Niño–Southern Oscillation, the primary driver remains human-induced climate change. The study has been published in the Journal of Climate.

Oceans are heating faster in two bands stretching around globe

The world’s oceans are heating faster in two bands stretching around the globe, one in the southern hemisphere and one in the north, according to new research led by climate scientist Dr Kevin Trenberth.

In both hemispheres, the areas are near 40 degrees latitude.

The first band at 40 to 45 degrees South is heating at the world’s fastest pace, with the effect especially pronounced around New Zealand, Tasmania, and Atlantic waters east of Argentina.

The second band is around 40 degrees North, with the biggest effects in waters east of the United States in the North Atlantic and east of Japan in the North Pacific.

“This is very striking,” says Trenberth, of the University of Auckland and the National Center of Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado. “It’s unusual to discover such a distinctive pattern jumping out from climate data,” he says.

Ocean heating upsets marine ecosystems, increases atmospheric levels of water vapour, which is a powerful greenhouse gas, and fuels rain-storms and extreme weather.

The heat bands have developed since 2005 in tandem with poleward shifts in the jet stream, the powerful winds above the Earth’s surface that blow from west to east, and corresponding shifts in ocean currents, according to Trenberth and his co-authors in the Journal of Climate.

The scientists processed an “unprecedented” volume of atmospheric and ocean data to assess 1 degree latitude strips of ocean to a depth of 2,000m for the period from 2000 to 2023, Trenberth says. Changes in heat content, measured in zettajoules, were compared with a 2000-04 baseline.

Besides the two key zones, sizeable increases in heat took place in the area from 10 degrees north to 20 degrees South, which includes much of the tropics. However, the effect was less distinct because of variations caused by the El Niño-Southern Oscillation climate pattern, Trenberth says.

“What is unusual is the absence of warming in the subtropics, near 20 degrees latitude, in both hemispheres,” he says.

Co-authors of the paper were Lijing Cheng and Yuying Pan, of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, John Fasullo of NCAR, and Michael Mayer of the University of Vienna and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts.

“Despite what Donald Trump thinks, the climate is changing because of the build-up of greenhouse gases, and most of the extra heat ends up in the ocean,” says Trenberth. “However, the results are by no means uniform, as this research shows. Natural variability is likely also at play.”

Journal Reference:

Trenberth, K. E., L. Cheng, Y. Pan, J. Fasullo, and M. Mayer, ‘Distinctive Pattern of Global Warming in Ocean Heat Content’, Journal of Climate 38, 2155–2168 (2025). DOI: 10.1175/JCLI-D-24-0609.1

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Auckland

Featured image credit: wirestock | Freepik