Summary:

In the shimmering heights of the Amazon rainforest, where light blazes and air runs dry, canopy trees face a constant energy challenge.

A new study published in New Phytologist by researchers at Michigan State University reveals how these towering forest giants navigate extreme sunlight and heat — and why their strategy matters for monitoring the forest’s future. Led by doctoral candidate Leonardo Ziccardi and Associate Professor Scott Stark, the research shows that Amazon trees absorb immense amounts of solar energy, much more than they can use for photosynthesis. To prevent damage, the trees must release this excess energy either as heat or light, through a process called chlorophyll fluorescence.

Over four years, Ziccardi climbed trees nearly 200 feet tall in Brazil’s central Amazon, recording thousands of leaf-level measurements across light and drought conditions. Using a handheld device called the MultispeQ, developed at MSU, he tracked how trees balanced light absorption and dissipation. The study identified a three-phase response to increasing light and dryness — revealing that under severe stress, trees may fluoresce more even as photosynthesis falters.

This finding has major implications for using satellite data to track forest health, especially under climate change conditions that bring hotter, drier air and clearer skies with more intense sunlight.

Amazon trees under pressure: New study reveals how forest giants handle light and heat

In a recent study, researchers at Michigan State University have uncovered how Amazon rainforest canopy trees manage the intense sunlight they absorb — revealing resilience to hot and dry conditions in the forest canopy while also offering a way to greatly improve the monitoring of canopy health under increasing extreme conditions.

The study was made possible by funding from the National Science Foundation and NASA.

The study, led by doctoral candidate Leonardo Ziccardi with Associate Professor Scott Stark in the MSU Department of Forestry, shows how tropical trees act like giant solar antennas — absorbing vast quantities of light energy that must be carefully managed. When trees absorb more energy than they can use for photosynthesis, it must be safely dissipated, either as heat or re-emitted as light — a process called chlorophyll fluorescence.

“It’s been a long journey,” said Ziccardi. “Since 2019, we’ve run multiple field campaigns across seasons, climbing giant trees in the heart of the Amazon to understand how these forests respond to environmental changes. We’ve spent hundreds of hours up in the canopy doing measurements — some of the most intense and rewarding work I’ve ever done.”

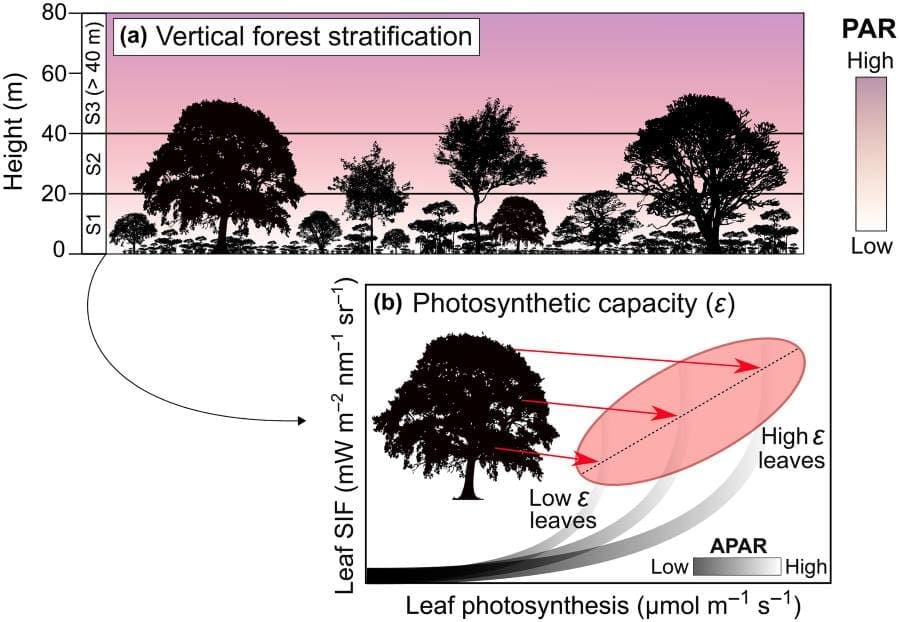

Ziccardi spent more than four years climbing trees nearly 200 feet tall in the central Amazon, measuring the fates of absorbed photons in thousands of leaves across many species, canopy heights, and light exposure conditions, producing a truly unique and unprecedented dataset.

Using a revolutionary handheld instrument — the MultispeQ, developed at MSU by co-author David Kramer in the MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory — Ziccardi captured how leaves in natural settings balance incoming light with their ability to photosynthesize or dissipate excess energy.

The findings offer a first-of-its-kind, high-resolution look at how the Amazon canopy navigates seasonal extremes. As the Amazon experiences increasing stress, due to both greenhouse gases and deforestation leading to hotter and drier conditions in the canopy, understanding how trees manage light energy is essential to predicting their future survival.

Not only does this climate change lead to greater physiological stress due to more frequent extreme conditions related to lower soil water availability and dry and hot air, it also can increase the amount of sunlight hitting the forest. This happens because drier conditions have less clouds and that lets more sunlight through. This study helps address whether Amazon trees can absorb and use this extra light under stressful conditions.

Despite facing intense sunlight and atmospheric dryness, many canopy leaves were able to continue photosynthesizing, but only by increasing their allocation to energy dissipation pathways. For the first time in the Amazon, the study revealed a nuanced, three-phase response of leaves to rising light and drought conditions.

Under low to moderate light, leaves balance energy use between photosynthesis and fluorescence, so these processes tend to increase and decrease together. As light and drought stress increase, however, this balance breaks down. Heat-protective dissipation mechanisms become overwhelmed, photosynthesis drops, and fluorescence can spike — signaling potential damage to the photosynthetic machinery.

The implications are critical for scientists using satellite observations of fluorescence — the so-called solar-induced fluorescence, or SIF — to monitor Amazon forest health. While SIF is often used as a proxy for photosynthesis, this study shows that photosynthesis and fluorescence do not always go up and down together. Under high light and stress, this relationship breaks down and leaves may fluoresce more even as their photosynthetic machinery declines, potentially leading to overestimates of ecosystem productivity during droughts.

Journal Reference:

Ziccardi, L.G., Kramer, D., Gonçalves, N., Nelson, B.W., Taylor, T., Albert, L.P., Campos, K.S., Prohaska, N., Restrepo-Coupe, N., Saleska, S.R. and Stark, S.C., ‘Seasonal and intracanopy shifts in the fates of absorbed photons in central Amazonian forests: implications for leaf fluorescence and photosynthesis’, New Phytologist (2025). DOI: 10.1111/nph.70183

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Lauren Noel | Michigan State University (MSU)

Featured image credit: Zdeněk Macháček | Unsplash