Summary:

Hurricanes striking the North Atlantic may increasingly arrive in rapid succession as climate change reshapes storm patterns. A new study published in Nature Climate Change finds that clusters of tropical cyclones – two or more storms active in the same ocean basin at the same time – are becoming more common in the region, a shift from historical patterns where the western North Pacific saw the highest occurrence.

Analysing historical records and high-resolution climate model simulations, researchers developed a probabilistic model to estimate the likelihood of cluster formation if storms occurred purely by chance. The model revealed that physical linkages between storms, such as atmospheric wave patterns, can significantly raise the odds of clusters beyond random expectation. Over the past 46 years, the probability of such events in the North Atlantic has risen from 1.4 ± 0.4% to 14.3 ± 1.2%, surpassing the western North Pacific. The trend is linked to a La Niña-like global warming pattern, which alters storm frequency and strengthens atmospheric waves that encourage cluster formation.

The findings identify the North Atlantic as an emerging hotspot for these compounding hazards, with implications for disaster preparedness in coastal nations facing back-to-back hurricanes.

North Atlantic faces more hurricane clusters as climate warms

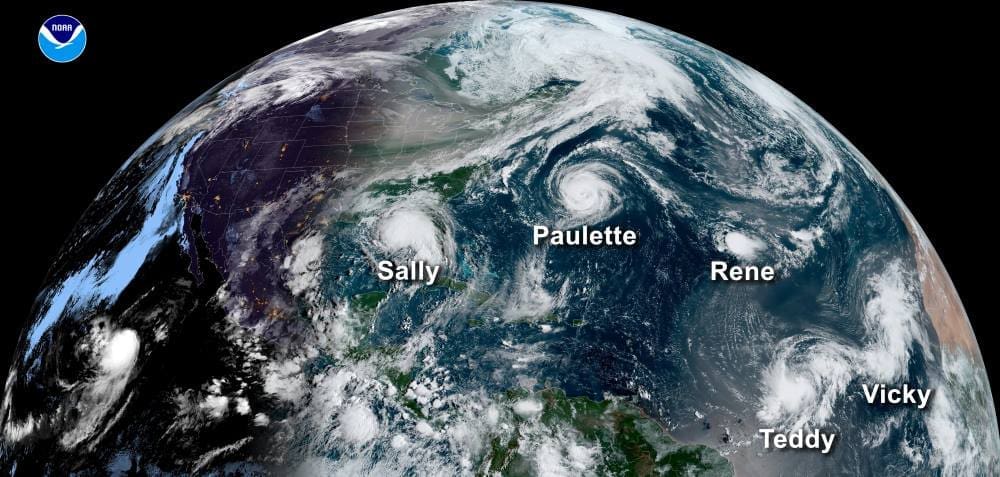

Tropical cyclones, commonly known as typhoons or hurricanes, can form in clusters and impact coastal regions back-to-back. For example, Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria hit U.S. sequentially within one month in 2017. The Federal Emergency Management Agency failed to provide adequate support to hurricane victims in Puerto Rico when Maria struck because most rescue resources and specialized disaster staffers were deployed for the responses to Hurricanes Harvey and Irma.

Tropical cyclone clusters describe the event that two or more tropical cyclones present simultaneously within the same basin. This phenomenon is not rare, as historically only 40% of tropical cyclones appeared alone. Beyond the combined impacts of individual storms, tropical cyclone clusters can cause disproportionate damage as coastal communities and infrastructures need time to bounce back from the impact of the first storm. Understanding tropical cyclone clusters and their future is thus important for coastal risk management.

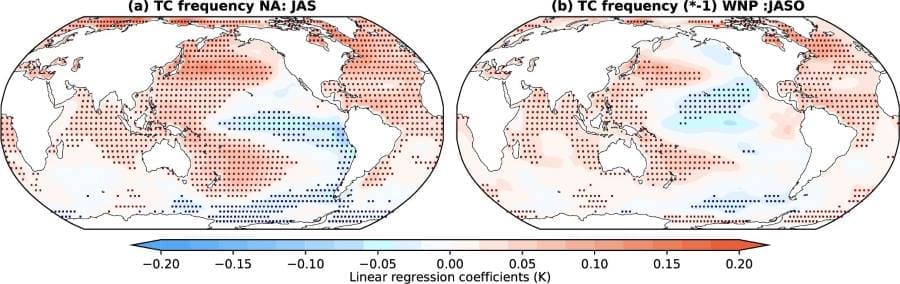

Analysing the historical observation of tropical cyclones, the authors found that during the past few decades, the chances for tropical cyclone cluster decreased in the Northwestern Pacific basin, while increased in North Atlantic basin.

“We tried to develop a probabilistic framework to understand this trend,” said Dazhi Xi, a climatologist at HKU who co-led the study and developed the methodology, “If tropical cyclone clusters are formed by chance, then only storm frequency, storm duration, and storm seasonality can impact the chance. So, as a first attempt we simulate the formation of tropical cyclone clusters by probabilistic modelling, considering only these three mechanisms, and hoped we could find why tropical cyclone clusters changed in the past decades.”

However, the probabilistic model is only partly successful. For some years, it significantly underestimates the chance of tropical cyclone cluster. It is because some storms coexist with other storms not simply by chance, rather, they have physical linkage.

“The previously seemed failed statistical model now soon becomes a powerful tool that can distinguish physical-linked tropical cyclone cluster with those by pure chance,” said Wen Zhou, a climatologist at Fudan University and the corresponding author of the study. For those years that the probabilistic model fails, the authors find that synoptic scale waves, a series of train-like atmospheric disturbances, enhance the chance of tropical cyclone cluster formation.

The study further discovered that the La-Niña-like global warming pattern, characterized by slower warming in the Eastern Pacific compared to the Western Pacific, is the reason behind the observed shifts in tropical cyclone cluster hotspot.

“The warming pattern not only modulates the frequency of tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic and Northwestern Pacific basins, but also impacts the strength of the synoptic scale waves, together causing the shift of tropical cyclone cluster hotspot from Northwestern Pacific to North Atlantic basin,” said Zheng-Hang Fu, a PhD student at Fudan University who co-led the study.

The research establishes a probabilistic baseline model for investigating tropical cyclone cluster events and their underlying physical mechanisms. This framework not only explains the observed shift of tropical cyclone cluster hotspot from the Northwestern Pacific to the North Atlantic basin, but also provides a transferable methodology applicable to other ocean basins worldwide. Importantly, the authors identify the North Atlantic as an emerging hotspot for tropical cyclone clusters in recent decades. This finding calls for heightened attention from Atlantic coastal nations, urging them to develop proactive strategies against these compounding hazards.

Journal Reference:

Fu, ZH., Xi, D., Xie, SP. et al., ‘Shifting hotspot of tropical cyclone clusters in a warming climate’, Nature Climate Change 15, 850–858 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41558-025-02397-9

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Fudan University

Featured image credit: NOAA