Summary:

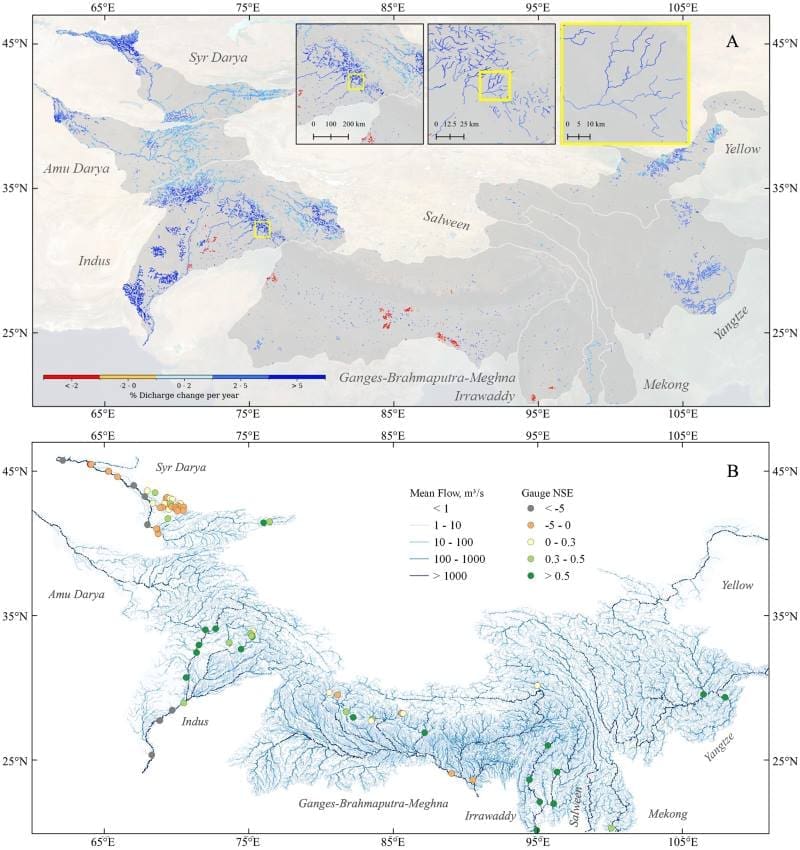

Glaciers melting across High Mountain Asia are increasing water flow in at least 10% of the region’s rivers, offering short-term benefits but posing long-term challenges, according to a new study in AGU Advances. The research, led by Jonathan Flores of the University of Massachusetts, examined over 114,000 river segments across the Himalayas, Hindu Kush, and surrounding ranges between 2004 and 2019, using satellite imagery from Landsat and PlanetScope combined with hydrologic modeling.

The study found that in parts of upstream rivers such as the Yangtze, Syr Darya, and Amu Darya, discharge rates grew by up to 8% annually, with some areas nearly doubling flow over a decade. While the extra water could enhance hydropower generation and irrigation, it also brings a rise in sediment load, which can damage infrastructure, reduce reservoir capacity, and disrupt ecosystems. The changes are most pronounced in glacier-fed western rivers, where climate change is accelerating ice loss. Researchers warn that as glaciers continue to shrink, their meltwater contribution will decline, threatening the long-term water supply for the two billion people dependent on these river systems.

The findings provide open-access data for communities and planners to adapt water infrastructure and management strategies to a rapidly changing hydrological landscape.

Surging Himalayan rivers bring benefits and risks to local communities

Rapidly melting glaciers are surging water volume in at least 10% of rivers in High Mountain Asia, including large rivers like Yangtze, Amu Darya and Syr Darya, according to a comprehensive new study of the region. In parts of upstream rivers, water flow nearly doubled over the course of a decade. Communities that depend on the rivers for power could benefit from the increase in river power, but additional sediment carried in the water may clog infrastructure. The increase is currently found specifically in upstream parts of the rivers, but downstream communities could face the same outcome as glaciers continue to melt.

Encompassing the Himalayas and the Hindu Kush and powerful rivers like the Yangtze, Yellow and Indus, High Mountain Asia is a complex geographic region that supplies water to around two billion people. The rivers are primarily fed by glaciers, snow and rainwater, but the river systems are changing as a result of climate change impacting temperature, monsoon season and droughts. Previous research has projected the glaciers in High Mountain Asia will lose between 29% and 67% of their total mass by 2100.

The new study investigated how the amount of water flowing through the river has changed as a result of melting glaciers and snow and changes in rainfall. This is the first study to look at the entire mountain range and its river and zoomed in to examine how each individual section of these rivers was impacted.

“Increased river discharge offers short term benefits such as more water for hydropower and agriculture, but it also signals sediment increase and glacier loss,” said Jonathan Flores, an engineer at the University of Massachusetts and lead author on the study. “If these glaciers continue to shrink, their meltwater contribution to river systems will decline, which will then threaten long term water availability for the downstream.”

The study was published in AGU Advances, which publishes high-impact, open-access research and commentary across the Earth and space sciences. The research measured more rivers than previous studies and divided them into 8-kilometer (5 mile) segments, which provided more detailed and tailored results.

Researchers found that 10% of rivers had seen an increase in river discharge, or the amount of water moving through the river, during the study period from 2004 to 2019. On average, these rivers saw the discharge rate increase of 8% per year. Sections of larger rivers that have more than 1000 cubed meters (265,000 gallons) of water moving through them per second, such as the Yangtze, had an average increase of over 2% per year, or an extra 5,300 gallons per second. Increases upstream may not correlate to increasing discharge further downstream, which is the case for many of the measured rivers.

The results show a double-edged sword. An increase in water can help with agriculture, electricity and general water usage, but an increase in water discharge directly correlates to an increase in stream power, or how much sediment like sand, silt and gravel is being moved through the river.

Sediment is natural in waterways, but an increase in sediment can come with consequences. Increased sediment can slow down machinery inside hydropower machinery, accumulate inside dams meant to hold water for the dry seasons, and damage river ecosystems with sensitive wildlife.

“The natural aquatic habitat can be altered by this increasing trend and the ecosystems that were previously stable can be altered and changed,” said Flores. Rivers in the western part of High Mountain Asia are fed by glaciers where rivers in the east are mostly filled through rain. As a result, it was primarily the rivers in the west that saw an increase in discharge because climate change is increasing the speed of melting glaciers.

They used over one million pictures from Landsat and PlanetScope satellites to track the changes of the rivers while confirming their estimates through water gauge measurements from various sites across the region.

The information they collected is open source for anyone to use. As plans are made for the construction of new dams or hydropower plants, this information could be used to increase how much water the plants could intake, meaning higher water storage or increased electrical capacity.

“Most of the water infrastructure like dams are designed based on historical data,” said Flores. “They can see that in this study we found that there are increasing trends in the data, so that can be a factor in their decision and planning and optimizing the design.”

Of the 1600 dams or planned dams measured in the study, 8% saw an increase in stream power, meaning more sediment moving through the dams. Flores said the increase in sediment could lead to higher stress being put on the machinery as it would need to move not just the water, but all the sand and dirt it begins to accumulate. Additionally, dams used to store water during the dry season could fill up with sediment and limit their capacity.

“When we tried to have a field visit in Nepal, we were able to visit these communities and hydropower plants and infrastructure, and we found that these are very important to them,” Flores said. “Most of the communities are reliant on hydropower electricity in this region.”

Flores said he hopes the open-source information can be used by local communities to better plan their water resource management for coming years.

Journal Reference:

Flores, J. A., Gleason, C. J., Brown, C., Vergopolan, N., Lummus, M. M., Stearns, L. A., et al., ‘Accelerating river discharge in High Mountain Asia’, AGU Advances 6, e2024AV001586 (2025). DOI: 10.1029/2024AV001586

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by American Geophysical Union (AGU)

Featured image credit: Vasiq Eqbal | Wikimedia | CC BY-SA