Summary:

Electric vehicles (EVs) lower greenhouse gas emissions across the entire United States, regardless of where drivers live, according to a new study from the University of Michigan published in Environmental Science & Technology.

The research team carried out the most comprehensive analysis to date, comparing 35 different combinations of vehicle class and powertrain, from gasoline pickups to fully electric sedans. Their “cradle-to-grave” approach factored in not just driving, but also manufacturing and disposal of vehicles, alongside local conditions such as grid emissions and climate. The results were clear: battery electric vehicles had the lowest lifetime emissions in every U.S. county, while gasoline-powered pickups ranked highest. For example, a fully electric pickup truck produced 75% fewer emissions than a conventional gas model.

The study also introduced a free online calculator that allows drivers to estimate emissions based on what and where they drive, offering a tool for consumers, policymakers, and industry alike.

EVs reduce climate pollution, but by how much? New U-M research has the answer

The analysis is the most comprehensive to date, the authors said, providing drivers with estimates of emissions per mile driven across 35 different combinations of vehicle class and powertrains. That included conventional gas pickups, hybrid SUVs and fully electric sedans with dozens of other permutations.

In fact, the team created a free online calculator that lets drivers estimate greenhouse gas emissions based on what they drive, how they drive and where they live.

The work was supported by the State of Michigan Department of Labor and Economic Opportunity and the U-M Electric Vehicle Center.

“Vehicle electrification is a key strategy for climate action. Transportation accounts for 28% of greenhouse gas emissions and we need to reduce those to limit future climate impacts such as flooding, wildfires and drought events, which are increasing in intensity and frequency,” said Greg Keoleian, senior author of the new study and a professor at the U-M School for Environment and Sustainability, or SEAS.

“Our purpose here was to evaluate the cradle-to-grave greenhouse gas reduction from the electrification of vehicles compared with a baseline of gasoline-powered vehicles.”

In addition to helping drivers understand their emissions, Keoleian and colleagues said this information will be valuable to the automotive industry and policymakers.

While EVs are driving into headwinds from a federal policy standpoint, the industry is committed to electrification, Keoleian said. As an example, Ford Motor Co. recently announced plans for a more affordable electric vehicle platform in what it called a “Model T moment” for the company.

“The government is backing off incentives, like the electric vehicle tax credit, but the original equipment manufacturers are heavily invested and focused on the technology and affordability of EVs,” said Keoleian, who is also a co-director of the U-M Center for Sustainable Systems, or CSS. “EVs are becoming the dominant powertrain in other parts of the world and manufacturers recognize that is the future for the U.S.”

The research team at U-M also included CSS/SEAS research specialists Christian Hitt and Timothy Wallington, as well as postdoctoral fellow Maxwell Woody and Alan Taub, professor in materials science and engineering. Taub is also the director of the U-M Electric Vehicle Center. Hyung Chul Kim, a research scientist at Ford, was another collaborator and Elizabeth Smith is the lead author, who worked on the project as a master’s student at U-M before graduating in May.

A high trim level lifecycle analysis

In their “cradle-to-grave” analysis, Keoleian and colleagues studied emissions numbers not just from driving vehicles, but also from making and disposing of them. In doing so, they considered an array of factors: powertrains, vehicle class, driving behavior and location.

The powertrains included conventional internal combustion engines, hybrid electric, plug-in hybrids, and fully electric, or battery electric. Vehicles with these powertrains are abbreviated ICEV, HEV, PHEV, and BEV, respectively. For vehicle class, they considered pickups, sedans and sport utility vehicles (they considered “generic” versions of these vehicles produced in 2025, which are representative of new vehicles in the marketplace).

Driving behavior included familiar factors such as highway vs. city driving, but also more modern considerations, like location of the vehicle and how often drivers of PHEVs were driving on battery power vs. gasoline.

Location affects emissions in two ways, Keoleian said. First, all vehicles—especially BEVs and PHEVs—use more fuel at lower temperatures and have lower range in locations with lower temperatures. Second, power grid emissions vary by location, so charging EVs in a county with a cleaner grid would emit less greenhouse gas.

In addressing all these variables in a single study, the researchers could make comparisons of emissions from different vehicles in an apples-to-apples way. This enables a detailed comparison of, say, a gasoline-powered pickup in Perry County, Pennsylvania, with a fully electric compact sedan in San Juan County, New Mexico.

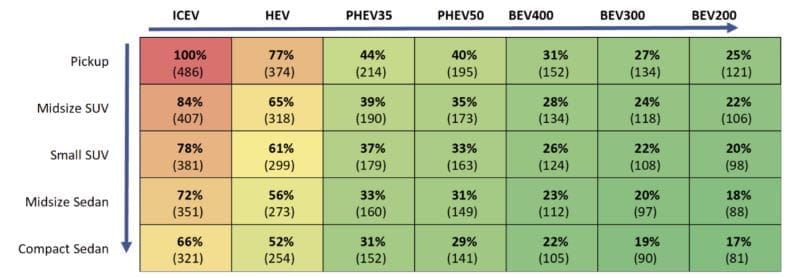

In addition to these detailed comparisons, the work also afforded important big-picture takeaways. The study showed for the first time that BEVs have lower emissions over their lifetime than any other vehicle type in every county in the contiguous U.S. On average, ICE pickup trucks were the highest emitters at 486 grams of carbon dioxide equivalent—a measure of greenhouse gas emissions—per mile. Switching to a hybrid pickup would reduce that by 23%, while a fully electric pickup represented a 75% drop.

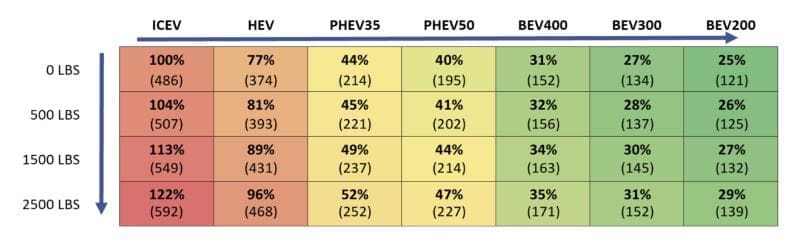

Another eye-catching stat came in the team’s analysis of how emissions changed while a pickup was hauling weight. A BEV pickup truck carrying 2,500 pounds still emitted less than 30% of an ICE pickup with no cargo.

Overall, compact sedan EVs had the lowest emissions at just 81 grams of carbon dioxide equivalent per mile—less than 20% of the per mile emissions of a gas-powered pickup. The lowest emission vehicle class was the compact sedan BEV with the lowest range, 200 miles. The emissions associated with producing batteries for vehicles with longer ranges bumped up their lifetime greenhouse gas contributions.

That also highlights another big take-away from the study, Keoleian said. Besides electrifying your ride, picking the smallest vehicle that suits your purposes will also reduce emissions.

“The thing is really matching your vehicle with your needs,” Keoleian said. “Obviously, if you’re in the trades, you may need a pickup truck. But you can get a battery electric pickup truck. If you’re just commuting to work by yourself, I’d recommend a sedan BEV instead.”

With the team’s online calculator, people who are interested in vehicle emissions can get answers personalized for their situations. The research study is open access and free to read.

Journal Reference:

Elizabeth Smith, Maxwell Woody, Timothy J. Wallington, Christian Hitt, Hyung Chul Kim, Alan I. Taub and Gregory A. Keoleian, ‘Greenhouse Gas Reductions Driven by Vehicle Electrification across Powertrains, Classes, Locations, and Use Patterns’, Environmental Science & Technology (2025). DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.5c05406

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Michigan

Featured image credit: Dave Brenner | U-M School for Environment and Sustainability | CC BY