Summary:

A new study published in Science suggests that Earth’s natural carbon cycle, long thought to stabilize global temperatures, could instead overcorrect – turning warming events into ice ages. Researchers from the University of California, Riverside found that under certain conditions, the planet’s system for recycling carbon can go into overdrive, pushing the climate far below its starting temperature.

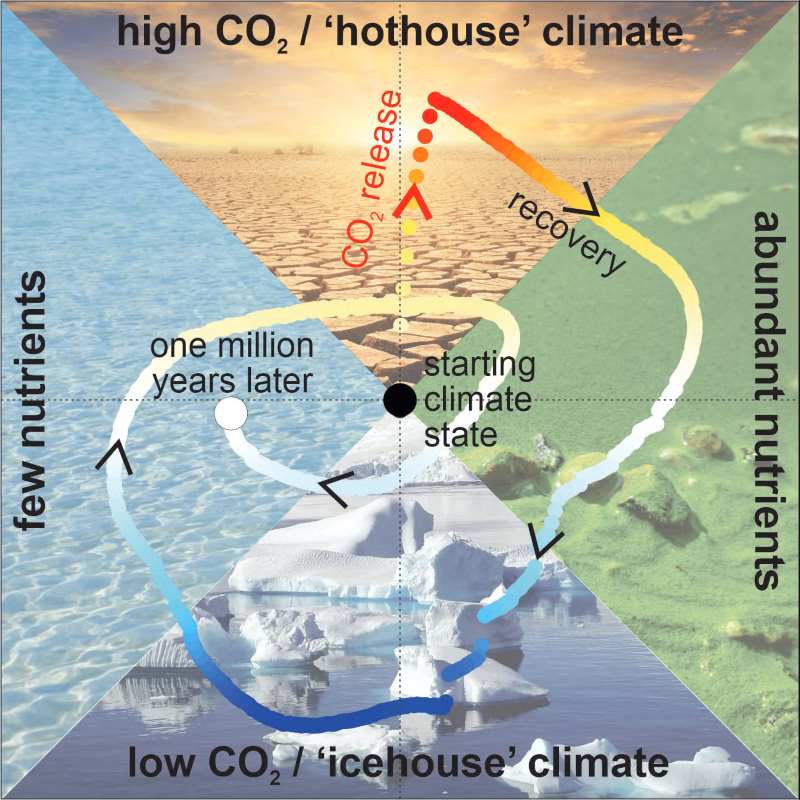

The traditional model assumes that as the planet warms, rainwater dissolves more carbon dioxide, accelerating the weathering of silicate rocks and gradually cooling the Earth. But according to co-author Andy Ridgwell, this feedback loop may not always operate smoothly. The study shows that rising CO₂ and higher temperatures can increase nutrient runoff and plankton growth, causing vast amounts of organic carbon to become buried in ocean sediments. This process removes carbon from the atmosphere faster than it can be replenished, triggering a dramatic cooling phase. “As the planet gets hotter, rocks weather faster and take up more CO₂, cooling the planet back down again,” said Ridgwell.

The team’s model helps explain how ancient “snowball Earth” events – when the planet was almost entirely frozen – may have occurred, and why such a scenario remains theoretically possible in the distant future.

Carbon cycle flaw can plunge Earth into an ice age

UC Riverside researchers have discovered a piece that was missing in previous descriptions of the way Earth recycles its carbon. As a result, they believe that global warming can overcorrect into an ice age.

The traditional view among researchers is that Earth’s climate is kept in check by a slow-moving but reliable natural system of rock weathering.

In this system, rain captures carbon dioxide from the air, hits exposed rocks on land – especially silicate rocks like granite – and slowly dissolves them. When this captured CO₂ reaches the ocean together with dissolved calcium from the rocks, they combine to form seashells and limestone reefs, locking the carbon away on the sea floor for many hundreds of millions of years.

“As the planet gets hotter, rocks weather faster and take up more CO₂, cooling the planet back down again,” said Andy Ridgwell, UCR geologist and co-author of the paper published in Science.

However, geological evidence suggests that ice ages earlier in Earth’s life were so extreme that the entire surface of the planet was covered in snow and ice. Therefore, the researchers say, a gentle regulation of planetary temperature cannot be the whole story.

The missing piece also involves carbon burial in the ocean. As CO₂ increases in the atmosphere and the planet warms, more nutrients like phosphorus get washed into the sea. These nutrients fuel the growth of plankton that take in carbon dioxide when they photosynthesize. Then when they die, they sink to the sea floor, taking that carbon with them.

However, in a warmer world with more algal activity, oceans lose oxygen, causing phosphorus to get recycled instead of buried. This creates a feedback loop where more nutrients in the water create more plankton, whose decay removes even more oxygen, and more nutrients get recycled. At the same time, massive amounts of carbon are buried, and the Earth cools.

This system doesn’t gently stabilize the climate, but instead overshoots, cooling Earth far below its starting temperature. In the study’s computer model, this could trigger an ice age.

Ridgwell compares all this to a thermostat working overtime to cool a house.

“In summer, you set your thermostat around 78°F (25.6°C). As the air temperature climbs outside during the day, the air conditioning removes the excess heat inside until the room temperature comes down to 78 and then it stops,” Ridgwell said.

Using his analogy, Earth’s thermostat isn’t broken, but Ridgwell suggests it might not be in the same room as the air conditioning unit, making performance uneven.

In the study, lower atmospheric oxygen in the geological past made the thermostat much more erratic, hence ancient extreme ice ages.

As humans add more CO₂ to the atmosphere today, the planet will continue to warm in the short term. The authors’ model predicts a cooling overshoot will occur. However, the next one will likely be milder because there is more oxygen in the atmosphere now than in the distant past, which dampens the nutrient feedback.

“Like placing the thermostat closer to the AC unit,” Ridgwell added. Still, it could be enough to bring forward the start of the next ice age.

“At the end of the day, does it matter much if the start of the next ice age is 50, 100, or 200 thousand years into the future?” Ridgwell wondered. “We need to focus now on limiting ongoing warming. That the Earth will eventually cool back down, in however wobbly a way, is not going to happen fast enough to help us out in this lifetime.”

Journal Reference:

Dominik Hülse, Andy Ridgwell, ‘Instability in the geological regulation of Earth’s climate’, Science 389, eadh7730 (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adh7730

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of California – Riverside (UC Riverside)

Featured image credit: Peter Mcnally | Pixabay