Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press roundup (November 26, 2025), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

Folklore sheds light on ancient Indian savannas

In the earliest text written in Marathi, a language of millions in western and central India, a 13th-century religious figure named Cakradhara points to an acacia tree as a symbol of the cycle of death and reincarnation.

It’s unlikely he imagined he would help today’s scientists understand the history of India’s vast lands.

But scholars say that centuries-old literary works like this could help reveal the history of the great expanses of savannas and grasslands that cover nearly 10% of India and more than a third of the land on Earth.

That history suggests that tropical grasslands aren’t the remains of former forests that they’re sometimes made out to be, which is important for deciding where to focus tree planting efforts in the future, researchers say.

In a new study to be published in the British Ecological Society journal People and Nature, scientists turned to historical accounts of plants in stories and songs set in western India to determine what vegetation once grew there.

“The take-home for me is how little things have changed,” said study author Ashish Nerlekar of Michigan State University. “It’s fascinating that something hundreds of years old could so closely match what is around today and contrast so much with what people romanticize the past landscape to be.”

The researchers came up with the idea for the study over coffee while comparing notes about their respective fields.

Co-author Digvijay Patil, a PhD student in archeology in the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research in Pune, mentioned he sometimes came across references to peculiar plants while combing through Sanskrit and Marathi texts for his research on sacred sites in western India.

Nerlekar, a plant scientist, recognized them as real species of trees and shrubs that dot the region’s savannas.

So the team started poring over folk songs, poems and myths written or performed in Marathi and dating as far back as the 13th century – very little of which exists in databases – to find references to wild plants and map their locations.

In the state of Maharashtra where the works were set, today some 37,485 square kilometers consist of open grassy expanses – an area two-thirds as big as Lake Michigan.

These areas are frequently misunderstood, said Nerlekar, a postdoctoral fellow in MSU’s Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior Program.

In policy and in popular imagination, tropical savannas in India and elsewhere have long been cast as the remains of former forests that were reduced by humans to their present state, and thus maligned as “wastelands.”

Under this view, they’re often earmarked for tree planting campaigns aimed at restoring forests to help absorb carbon dioxide and address the climate crisis.

But this and other studies paint a different picture of their past.

The researchers uncovered mentions of 44 species of wild plants, nearly two thirds of which are characteristic of savannas.

For example, in one passage of the epic poem “Adi Parva,” dated to about the 16th century, cowherders are attracted to the “empty” and “thorny” landscape of the Nira River valley by its abundant grass.

Another account involving the death of a 15th-century poet-saint at a pilgrimage site called Pandharpur tells of a taraṭī tree – which scientists know as a sun-loving species called Capparis divaricata – that sprouts from her grave.

The researchers also found eight references to the thorny acacia tree that Cakradhara singled out, a feathery-leaved species with pale yellow bark and white flowers called Vachellia leucophloea.

“It’s a pretty iconic tree in the region, and it was common at that time also,” Nerlekar said.

This and other windows into the past suggest that the region’s savannas stretch back at least 750 years, existing long before the deforestation that took place in India during British rule.

Previous lines of evidence suggest that many of the world’s tropical savannas including those in India are even more ancient.

For example, the fossilized remains of pollen grains and grass-feeding hippos and other animals suggest that the plants that grew in the region tens of thousands of years ago were typical of savannas, not forests.

There are good reasons to preserve savannas and grasslands today, Nerlekar said.

In India alone, they are home to more than 200 plant species found nowhere else on Earth – many of which were only recently described by science, and remain at risk as land is converted to farms and other uses.

“A lot of savanna biodiversity is also sacred, which means they have cultural value in addition to ecological value,” Nerlekar said.

Savannas also act as carbon sinks, because they absorb carbon dioxide that would otherwise stay in the atmosphere and contribute to warming.

And in Asia, Africa, Australia, and South America, they provide fodder for hundreds of millions of cattle, sheep and other grazing livestock.

An estimated 20% of the global human population rely on savannas and grasslands for their livelihoods. The researchers say these benefits could be lost if efforts to mitigate climate change include planting trees in places where there was no forest to begin with.

“These centuries-old stories provide us a rare glimpse into the past, and that the past was a savanna past, not a forested past,” Nerlekar said.

***

This research was supported by grants from Michigan State University and IISER Pune.

Journal Reference:

Nerlekar, A. N., & Patil, D., ‘Utilizing traditional literature to triangulate the ecological history of a tropical savanna’, People and Nature online ver., 1–18 (2025). DOI: 10.1002/pan3.70201

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Robin Smith | Michigan State University (MSU)

Study identifies great potential for forest restoration in urban fringe areas

A study conducted at the University of São Paulo (USP) by researchers from the Nucleus of Analysis and Synthesis of Nature-Based Solutions (BIOTA Synthesis), a FAPESP Science Center for Development (SCD), identified approximately 410,000 hectares in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, with potential for forest restoration in urban fringe areas.

These peripheral areas of urban centers are characterized by diverse land uses, such as residential neighborhoods, agricultural land, recreational spaces, urban infrastructure, and aquatic zones. They are not normally included in surveys of potential restoration areas. The findings of the study are equivalent to nearly one-third of the state’s goal of restoring 1.5 million hectares by 2050.

The results of the study were published in the journal Scientific Reports.

“These are interesting areas because they’re close to cities and people, which maximizes the benefits of restoration. We saw that regeneration has exceeded deforestation since 2005, despite urban pressure,” Luciana Schwandner Ferreira explains to Agência FAPESP. She is a researcher at the Institute of Advanced Studies (IEA) at USP and the lead author of the study, which was funded by a scholarship from FAPESP.

The research analyzed three decades (1990-2020) of deforestation and regeneration data collected by the MapBiomas project across the state of São Paulo. MapBiomas is a collaborative network formed by non-governmental organizations, universities, and technology startups that maps land cover and land use in Brazil. For the first time, the research distinguished between dense urban areas, urban fringes, and rural areas. The results show that forest transition has already occurred in all regions studied. Urban fringes show the highest rates of regeneration, albeit with limited support from public policies.

“Even without specific policies, urban fringes already show significant regeneration rates, indicating significant potential for forest restoration. This process could be stimulated and expanded through public policies focused on these areas, bringing restoration closer to the 96% of the state’s population that currently lives in cities,” says Jean Paul Metzger, a professor at the Institute of Biosciences (IB) at USP and coordinator of BIOTA Synthesis, who led the study.

The São Paulo macrometropolis, a region comprising 174 municipalities, is an interesting case for considering restoration on urban fringes. Its proximity to well-preserved areas, such as the Serra do Mar State Park and other conservation units, may facilitate natural regeneration and reduce costs. In cases where active planting is necessary, proximity to the most populous area of the state facilitates access to labor and job creation.

According to the researchers, restoration projects are easier to implement in areas where the opportunity cost of land is low – that is, where the land’s value and potential gains from other uses are low. However, the environmental and social benefits are amplified when these projects are carried out near cities.

In addition to promoting biodiversity and protecting the environment, restoring urban and peri-urban areas can contribute to human health and well-being, regulate the climate, mitigate extreme events, improve water and air quality, and provide recreational spaces.

Numbers

The 410,000 hectares with restoration potential are equivalent to 51% of the total area of these regions. Of these, 235,000 hectares are located in the São Paulo macrometropolis, directly benefiting 32.7 million people.

Thirty-nine thousand hectares of the total potential areas are in regions that are both at risk and subject to permanent preservation (APP), such as riverbanks and hilltops. These areas require urgent restoration under the Brazilian Forest Code (Law No. 12,651/2012).

“More detailed studies on ecological and socioeconomic suitability still need to be carried out to guide which strategies are most appropriate in each case,” says Ferreira.

The study acknowledges that urban fringes are highly contested territories, often earmarked for urban expansion or agriculture, particularly small-scale family farming. Therefore, restoration efforts will need to coexist with other uses. The researchers take into account the need to mitigate social risks, such as the displacement of vulnerable populations or gentrification processes associated with environmental improvement.

The authors also emphasize that urban fringes have many different actors and socio-environmental characteristics. This requires the types of restoration to be defined in a contextualized manner. In some cases, natural regeneration and ecological restoration are prioritized. In others, it is productive models that integrate the cultivation of native species for food and wood. In certain contexts, the focus is on objectives related to urban green infrastructure.

***

The work was also supported by FAPESP through the project “Resilience and adaptation to climate change in cities: time to act with nature-based solutions” and postdoctoral fellowships (22/07415-0 and 22/09161-6).

Journal Reference:

Ferreira, L.S., di Giulio, G., Chaves, R.B. et al., ‘Urban boundaries are an underexplored frontier for ecological restoration’, Scientific Reports 15, 34829 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-19699-9

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP)

Biobased concrete substitute can give coastal restoration a natural boost

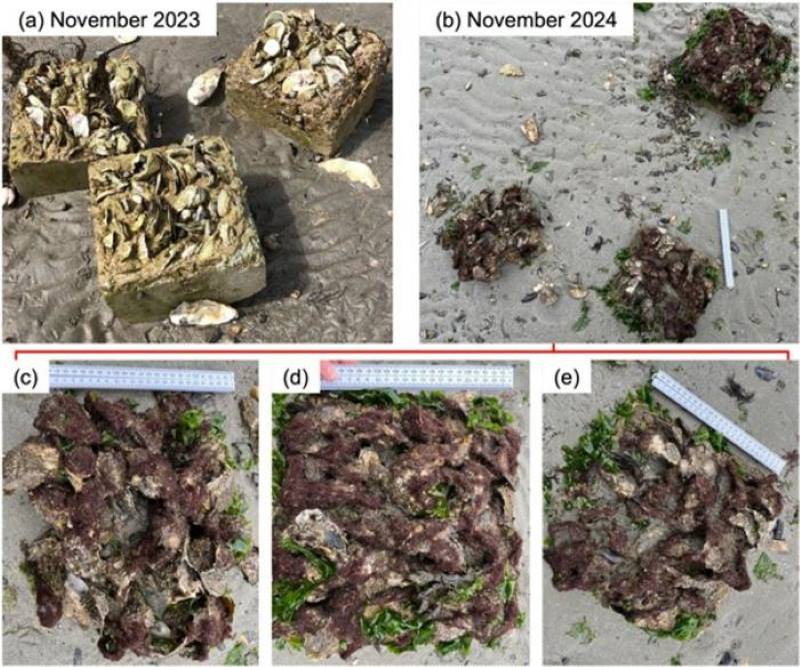

Using different variants of Xiriton NIOZ researchers set to work at the research institute in Yerseke. Xiriton is easy to make with chopped dried grass, volcanic pozzolan, slaked lime, shells, sand and seawater. But is it also suitable for restoring tidal areas such as salt marshes and shellfish reefs where necessary?

They published their work in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

Covered with life

The idea is that temporary structures in tidal areas provide a place where mussels and oysters can settle in areas where they have disappeared or declined significantly. The researchers placed blocks of Xiriton on the mudflat in Yerseke, where they were exposed to the tides twice a day. ‘After a year, every block was around 70 per cent covered with life such as oysters, mussels and algae,’ says PhD candidate Victoria Mason. ‘This indicates that Xiriton blocks are not only cheap, sustainable and practical to manufacture on a large scale, but also suitable for use in enhancing settlement and potentially restoring biodiversity. By adjusting the lifetime of the material, it can also break down naturally into harmless substances once a reef can sustain itself, instead of remaining permanently in the ecosystem.’

Cordgrass or bamboo

The researchers used cordgrass (Spartina anglica), which is widely available locally, and Elephant grass (Miscanthus giganteus), to make Xiriton. Other types of grass, such as reed or bamboo, could also be used, as long as they are harvested sustainably. Depending on the drying time of the material and the amount of binder in the mix, it becomes stronger. Mason: ‘After five weeks of drying, it was at its hardest.’ The research showed that the acidity of the material is favourable. Mason: ‘With a pH value of 8 to 9, it is much more neutral than standard concrete, which is more alkaline. Concrete has a pH of around 13, which can be unfavourable for organisms that need to settle on it.’

Coffie cup shaped objects

The researchers found that after 63 days of heavy flow, Xiriton is as strong as concrete alternatives such as those made with Roman cement. In the so-called Fast Flow Fume (see photo), for example, they unleashed a strong current on pieces of Xiriton that had been made using coffee cups as moulds, in an enhanced erosion experiment to test the adjustability of the material lifetime. That was the task of Jente van Leeuwe, then a master’s student in Earth & Environment at WUR, now a PhD student at NIOZ. ‘We used those coffee cups to place the material in the flow instead of having the flow go over the structure, like with tiles.’

Flexible, temporary and cheap

Mason: ‘For the purpose of intertidal restoration, we need materials that are not environmentally harmful in the short or long term. They must be flexible in terms of what shapes we can build, and temporary, so they don’t require expensive removal or leave harmful products in the environment. As well as that, they need to be inexpensive enough to be upscaled to larger projects and different areas.’

Follow-up study

The researchers want to conduct a follow-up study to determine whether Xiriton is also suitable for large, wave-breaking structures. Dependent on the composition, the lifetime of these semi-permanent structures could be altered – to be long enough to serve as temporary scaffolding for natural reef formation.

Almost everything you can do with bricks

The developer of Xiriton is Swiss Frank Bucher, who lives in Stiens, Friesland. Back in 2009, he won an award for the concept, which he says can be used to build anything you can build with bricks. ‘All buildings up to three stories high, for example. But you don’t have to bake it and you don’t need clean drinking water. You can make it with ditch or sea water.” To his regret, the material has not yet been used in the construction industry. ‘The combination with wood enables new construction concepts, including for hydraulic engineering. Wood reinforces Xiriton, and Xiriton protects the wood.’ In the world of coastal restoration, people are open to it, Bucher notices. Xiriton is also the subject of research at Van Hall Larenstein University of Applied Sciences.

Mason is nearing the end of her PhD research. ‘I have enjoyed working with Xiriton as a more practical, applied side to my research. We were able to explore concepts of ecosystem restoration with a view to offering a realistic, non-harmful and globally upscalable option to placing materials into ecosystems, where intervention is required.’

Not a luxury, but a necessity

Senior researcher Jim van Belzen, also involved in the publication, places the research in a broader perspective. ‘The built world now weighs more than all the biomass on Earth. If we really want to reduce our footprint, we need to radically rethink the way we build. New biobased concepts – where nature, circularity and regeneration are central – are not a luxury, but a necessity. The technology is still in its infancy, but biodiversity will not wait.’

According to Van Belzen, Xiriton offers prospects for nature-inclusive applications in coastal protection and ecosystem restoration. The material combines the strength and malleability of concrete with a much smaller ecological footprint and could potentially be used for breakwaters, seawalls or artificial reefs that enhance natural processes. ‘The future of water safety? It could well be greener than stone and concrete.’

Journal Reference:

Mason VG, van Leeuwe J, Bouma TJ, Sinke D, Varley D, Heide Tvd, Temmink RJM, Bucher F and van Belzen J, ‘Using local materials for scalable marine restoration: Xiriton as a nature-enriching, low impact building material’, Frontiers in Marine Science 12: 1661288 (2025). DOI: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1661288

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ)

Fossil fuels speed up shifts in Europe’s winter rainfall

As COP30 negotiations failed to secure new pledges to cut fossil fuels new research shows that the burning of coal, oil and gas is already driving dangerous increases in winter rainfall across northern Europe – decades ahead of climate model projections.

Professor Hayley Fowler, Professor of Climate Change Impacts at Newcastle University, said:

“What we saw recently in Monmouth is another stark reminder that the UK is already facing severe weather impacts driven by our continued reliance on fossil fuels. Our new study shows that winter rainfall is increasing far more quickly than climate models project – reaching levels now that models don’t detect until the 2040s.

“As fossil fuels were taken out of the COP30decision text, it is vital that politicians understand the science: the risks are accelerating, and delaying action will put more lives at risk.

“I urge members of the public to contact their MP and ensure they attend the National Emergency Briefing on 27 November in Westminster, where I will be speaking alongside Chris Packham and many of the UK’s leading scientists. We urgently need our politicians to take these escalating weather events seriously. The UK must urgently transition away from fossil fuels and invest in resilience now, not decades from now.”

Burning of fossil fuels has accelerated Europe’s winter rainfall changes by 23 years

A new study published in the journal Environmental Research Letters reveals that warming caused by the burning of fossil fuels has accelerated shifts in Europe’s winter rainfall patterns by more than two decades. Conditions expected in the mid-2040s are already being observed today.

Newcastle University climate experts found that winters in Northern and central Europe – including the UK – are becoming significantly wetter, increasing winter flood risk. In contrast, winters in the Mediterranean are becoming markedly drier, deepening drought and water scarcity. Climate models significantly underestimate both the speed and magnitude of these changes.

The team analysed winter rainfall in Europe between 1950 and 2024 and examined how large-scale atmospheric circulation patterns, including shifts in the North Atlantic jet stream, interact with human-caused warming. Their methods separated the natural variability from the effects of burning fossil fuels.

Even after accounting for natural climate fluctuations, observed changes were much stronger than climate models predict for the same period.

Flood risks underestimated across northern Europe

These trends are contributing to increases in winter flood risk in Northern Europe. Lead author Dr James Carruthers, Newcastle University School of Engineering, said:

“Future winter flood risk, especially in northern Europe, is likely being significantly underestimated. The level of risk we face today is already greater than climate models indicate.”

The findings raise urgent concerns for national adaptation plans, infrastructure investment, and emergency preparedness across Europe which may be underestimating climate risks for the next 20 to 30 years. The authors stress that the UK and Europe must accelerate and strengthen its adaptation planning to protect communities from worsening winter floods, as many systems are planned using these climate model projections. They plan to continue investigating whether similar early intensification is occurring in other seasons.

Why this matters for UK policymakers

- The UK is already experiencing rainfall levels not expected until the mid-2040s.

- Flood defences, drainage systems, and emergency services may be underprepared for current levels of risk.

- Without rapid action, communities will face increasingly severe and frequent flood events, damaging homes, transport networks, and critical services.

- The results come at a pivotal moment, as global climate negotiations stall on the phase-out of fossil fuels.

Journal Reference:

James G Carruthers, Hayley J Fowler, Daniel Bannister and Selma B Guerreiro, ‘Dynamical adjustment reveals spatial patterns of wetting and drying in European winter precipitation’, Environmental Research Letters 20, 11: 114085 (2025). DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/ae198b

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Newcastle University

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay