Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press roundup (January 18, 2026), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

— Press Release —

Fossils reveal ‘latitudinal traps’ that increased extinction risk for marine species

The findings, published in Science, provide new insight towards understanding patterns of biodiversity distribution throughout Earth history to the present day, and highlight which modern species may be more at risk of extinction due to climate change.

The researchers analysed over 300,000 fossils for over 12,000 genera of marine invertebrates, combining these with reconstructions of continental arrangements at different times in the past. This enabled them to run a powerful statistical model to test the hypothesis that the orientation and shape of a coastline influenced a taxon’s chance of extinction.

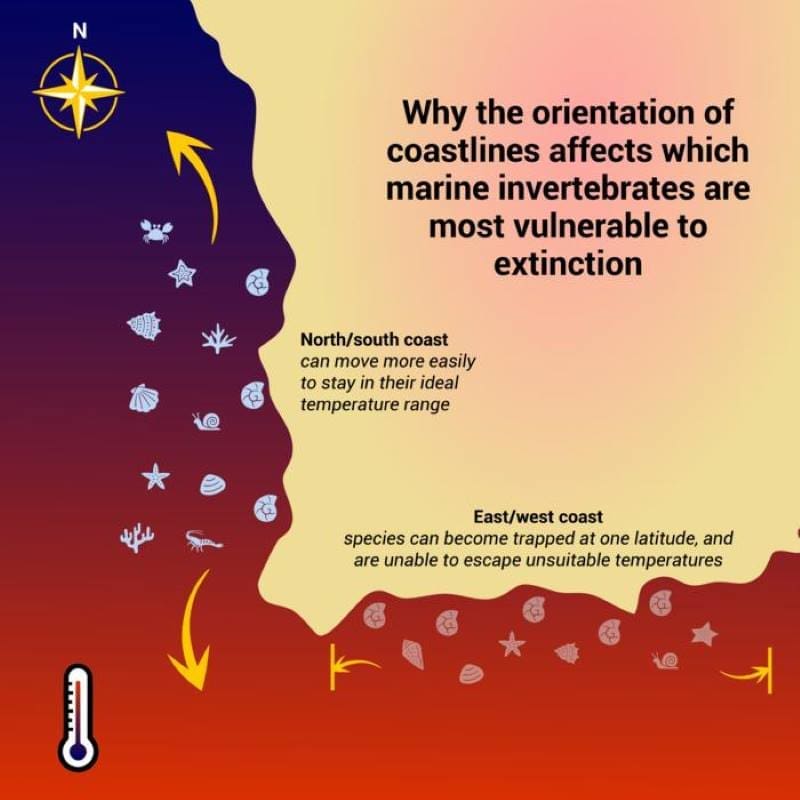

The model revealed that invertebrates living in environments such as east-west orientated coastlines, islands or inlands seaways, where migration to a different latitude was difficult, or impossible, were consistently more vulnerable to extinction than those which could move more easily in a northwards or southwards direction.

Study co-author Professor Erin Saupe (Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford) said: “Generally, coastlines with a north-south orientation better allowed species to migrate during periods of climate change, enabling them to stay within their ideal temperature tolerance range. This reduces their risk of extinction. Conversely, groups that are trapped at one latitude, because they live on an island or an east-west coastline, for example, are unable to escape unsuitable temperatures and are more likely to become extinct as a result.”

The researchers were also able to show that this effect was heightened during mass-extinctions and hyperthermal (extremely warm) periods, and that coastline geometry became even more important for survival during these times.

Lead author Dr Cooper Malanoski (Department of Earth Sciences) said: “This shows how important palaeogeographic context is – it allows taxa to track their preferred conditions during periods of extreme climate change. And palaeogeography could provide one explanation for why some mass extinctions are more severe than others – some continental configurations may make it harder for groups to avoid the extreme climate changes during these events.”

The findings highlight that present-day species in isolated habitats that cannot easily migrate to a different latitude may be especially vulnerable to anthropogenic climate change. This information could be useful when determining conservation priorities and for identifying vulnerable marine populations into the future, especially those humans rely on for ecosystem services.

Professor Saupe added: “This work confirms what many palaeontologists and biologists have suspected for years – that a species’ ability to migrate to different latitudes is vital for survival. By examining the fossil record of marine invertebrates restricted to shallow marine environments, we have been able to test this hypothesis with rigorous statistical analyses. An exciting next step is to see if we can observe this effect today.”

The study was conducted in collaboration with the University of California, Berkeley (USA), Stanford University (USA), University of Leeds (UK), and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (Panama).

Journal Reference:

Cooper M. Malanoski et al., ‘Paleogeography modulates marine extinction risk throughout the Phanerozoic’, Science 391, 6782, pp. 285-289 (2026). DOI: 10.1126/science.adv2627

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Oxford

— Press Release —

Learning about public consensus on climate change does little to boost people’s support for action, study shows

Providing accurate information about the climate crisis can help to correct misperceptions about how much public support exists for action.

However, simply showing that others support climate action does not, on its own, have a meaningful impact on people’s own beliefs or behavioural intentions, a new study based on data from Germany shows, challenging common expectations about the power of public consensus to drive climate action.

The study finds that learning about widespread public support for climate action policies can initially make people think such policies are more politically feasible and more likely to be implemented. However, these effects are small and short-lived, raising questions about how effective such communication strategies are in practice.

The data were collected in collaboration with YouGov in Germany in 2021 and include 2,801 respondents. The same people were surveyed twice, around two weeks apart. Some participants were shown information about how widespread public support for climate action actually is in Germany. Others were not shown this information.

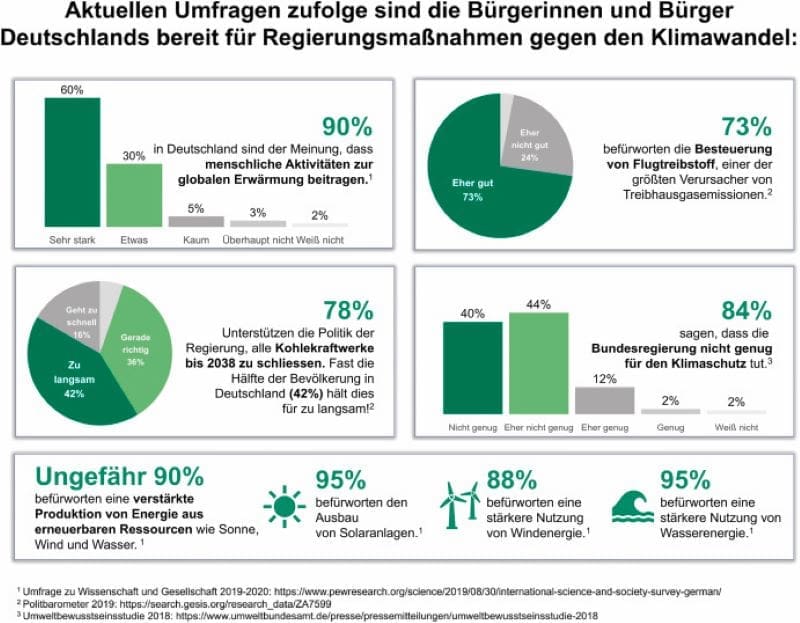

Overall, people in Germany had a fairly accurate sense of how much public support exists for climate action. On average, they did not believe that only a small minority supports action to combat climate change. At the same time, some people underestimated how many others supported climate action and specific climate policies.

Among those who underestimated public support, the information shown in the study made a clear difference. When presented with evidence of how widespread support for climate action is, they updated their views about public opinion. This learning was not fleeting. It was still visible when the same people were surveyed again two weeks later.

Importantly, this learning was limited to perceptions of public opinion. Knowing that many others supported climate action did not change people’s own beliefs about climate change, such as whether human activity is the main cause, their personal preferences for climate policies, or their intentions to change their behaviour, for example using public transport instead of a car.

There was one partial exception. People who learned about broad public support initially found political climate action more feasible. For example, they were slightly more likely to think that policies such as taxing goods based on their CO₂ emissions could realistically be implemented. However, this effect faded by the follow-up survey.

The study, published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology, was conducted within the Debunker Lab, led by Jason Reifler (University of Southampton; formerly University of Exeter). The research is led by Matthew Barnfield (Queen Mary University of London) and co-authored by Paula Szewach (Barcelona Supercomputing Center), Sabrina Stöckli (University of Bern), Florian Stoeckel (University of Exeter), Jack Thompson (University of Leeds), Joseph Phillips (Cardiff University), Benjamin Lyons (University of Utah), and Vittorio Mérola (Durham University).

Dr Barnfield said: “Learning how much consensus there is in support for policy action on climate change seems to durably increase people’s perceptions of that consensus, even for policies that we didn’t specifically tell them about. But that does not seem to have much effect on how much people support or even themselves adopt environmentally friendly actions. This finding might disappoint experts who have argued for this approach as a way to accelerate climate action in democracies.”

Professor Stoeckel added: “People do learn what others think on climate change, and that learning can persist. At the same time, our study shows clear limits to what can be expected from this strategy. Simply telling people that climate action is widely supported is likely not enough to change beliefs, preferences, or behaviour.”

Journal Reference:

Matthew Barnfield, Paula Szewach, Sabrina Stöckli, Florian Stoeckel, Jack Thompson, Joseph Phillips, Benjamin Lyons, Vittorio Mérola, Jason Reifler, ‘Information on public opinion has lasting effects on second-order climate beliefs, but minimal and ephemeral effects on first-order beliefs’, Journal of Environmental Psychology 110, 102901 (2026). DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2026.102901

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Kerra Maddern | University of Exeter

— Press Release —

UC Irvine public health experts highlight climate change-driven nutrition gaps

Environmental factors driven by climate change are already shaping what ends up on Americans’ plates and how nutritious it is, according to a new perspective paper by researchers at the University of California, Irvine’s Joe C. Wen School of Population & Public Health.

Rising carbon dioxide levels, extreme weather events, air pollution and shifting ecosystems are disrupting food production and supply chains, often in ways that make healthy food harder to find or afford. The paper examines how these forces may quietly erode the nutritional quality of everyday foods, from grains to fruits and vegetables, with consequences for long-term health.

As crops are damaged by floods, heatwaves and droughts, and as environmental conditions alter the nutrient content of staple foods, communities – especially those already facing food insecurity – may be at greater risk of nutrient deficiencies. The authors assert that this raises urgent questions about whether dietary supplements could help fill emerging nutrition gaps or support health during environmental stress.

“Environmental change is not only an ecological issue. It’s a nutrition and public health issue,” said Margaret Nagai-Singer, first author of the paper and a research fellow in Wen Public Health. “When the food system becomes less stable or less nutritious, people feel it in very real ways – in their health, their medical costs and their daily lives.”

Studies have shown that higher carbon dioxide levels can reduce iron, zinc and protein in staple crops like wheat and rice. At the same time, extreme weather events can disrupt food distribution and limit access to fresh, nutritious foods, particularly in low-income and disaster-affected communities. These shifts may worsen chronic conditions and widen existing health disparities.

Exposure to extreme heat, wildfire smoke, air pollution and climate-sensitive infectious diseases can also trigger inflammation, oxidative stress and other biological responses that affect health. Some research suggests that certain nutrients may help protect against these stressors, but more detailed knowledge is lacking.

Dietary supplements are often used to help people meet recommended nutrient intakes, and the researchers note that they could become more relevant as environmental pressures grow. They also caution that questions about safety, effectiveness, affordability and appropriate use – especially across different ages, health conditions and environmental exposures – remain largely unanswered.

Additional research is needed in three key areas: understanding nutrient gaps linked to environmental change; determining whether supplements can help the body cope with stressors such as heat, air pollution and infectious diseases; and evaluating how dietary choices and the supplement industry itself affect the environment.

The environmental footprint of dietary supplements, including how ingredients are sourced and how products are manufactured and packaged, is an issue that may matter more to consumers as awareness of sustainability grows.

“Dietary supplements are not a substitute for a healthy diet or for fixing the underlying problems in our food system,” said Jun Wu, senior author of the paper and a professor of environmental and occupational health in Wen Public Health. “But as environmental challenges intensify, it’s important to understand whether they can play a limited, evidence-based role alongside broader solutions.”

The researchers emphasize that answering these questions will require collaboration across public health, nutrition, environmental science and policy. Their goal is to inform future research and public health decisions as climate-related changes continue to influence what people eat and how those choices affect their health.

Journal Reference:

Margaret A Nagai-Singer, Jun Wu, ‘The Role of Dietary Supplements in Environmental Challenges’, Advances in Nutrition 17, 1 (2026). DOI: 10.1016/j.advnut.2025.100566

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of California, Irvine (UC Irvine)

— Press Release —

Rethinking climate impacts through human wellbeing

Human wellbeing is increasingly recognized as a better benchmark for sustainable development than GDP. Yet, while GDP is losing its prominence as a measure of wellbeing, climate impacts are still mostly assessed in monetary terms, most notably through the social cost of carbon, which is based solely on economic damage. The study, published in Global Sustainability, takes an important step toward measuring climate impacts in terms that matter directly to people by shifting the focus from economic output to human wellbeing itself.

Linking climate, society, and human wellbeing

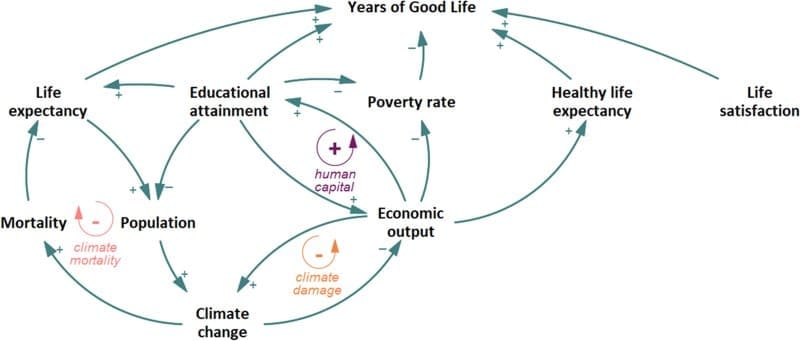

Using a global systems model together with the Years of Good Life (YoGL) indicator developed at IIASA, the researchers show how climate change, economic development, and social conditions combined shape long-term human wellbeing. Years of Good Life measures how many years individuals can expect to live in good physical and cognitive health, above poverty, and with overall life satisfaction.

By explicitly modeling feedbacks between natural, human, and economic capital and Years of Good Life, the analysis provides the first quantitative estimation of the core equation of sustainability science using an empirically grounded and intuitive wellbeing metric, going well beyond earlier approaches that could not clearly trace how environmental change affects wellbeing over time.

Key results: up to 11.3 Years of Good Life at stake

The results show that strong climate action could increase individual wellbeing by up to 10.4 Years of Good Life on average, while high-emissions pathways could reduce lifetime wellbeing by as much as 11.3 years. Younger generations face the highest marginal wellbeing losses from today’s emissions, highlighting pronounced intergenerational inequities. The analysis also reveals gender differences, with men experiencing higher marginal wellbeing losses per unit of carbon emitted, despite women often having lower overall wellbeing levels.

“Our study demonstrates that wellbeing can be modeled in a forward-looking and integrated way, capturing the links between climate change, the economy, and social development,” says study author and IIASA Senior Research Scholar, Sibel Eker. “For policymakers, the approach offers a way to compare climate and development pathways, with human wellbeing – not just economic output – at the center of decision-making.”

“For the first time, we can quantify how changes in climate and other forms of natural, human or economic capital translate into gains or losses in human wellbeing across generations and genders. It is time to think about the wellbeing cost of carbon instead of focusing only on economic costs, because what ultimately matters is how today’s emissions shape the quality of life of future generations,” concludes IIASA Distinguished Emeritus Research Scholar and coauthor, Wolfgang Lutz.

Journal Reference:

Eker S, Reiter C, Liu Q, Kuhn M, Lutz W., ‘Wellbeing cost of carbon’, Global Sustainability 9: e1 (2026). DOI: 10.1017/sus.2025.10042

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA)

Featured image credit: Freepik (AI Gen.)