Summary:

Olympic Games carbon emissions remain in the millions of tonnes per edition, raising questions about whether the world’s largest sporting event can align with international climate targets. A new study by researchers at the University of Lausanne, published in The Geographical Journal, provides one of the first systematic assessments of recent Olympic carbon footprints and compares them with the reductions required under the 2015 Paris Agreement.

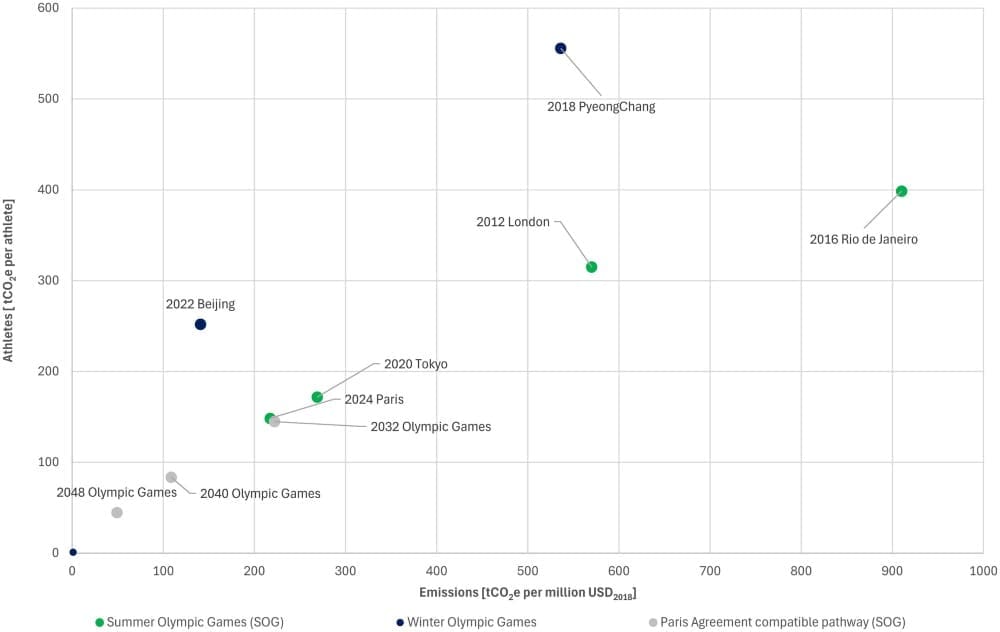

The analysis shows that since 2012, emissions from individual Summer and Winter Games have ranged from 1.59 to 4.5 million tonnes of CO2e. Rio 2016 reached the upper end of that range, while Paris 2024 reduced its footprint to 1.59 million tonnes through limited new construction and improved local transport planning. Even so, international spectator travel accounted for nearly half of total emissions.

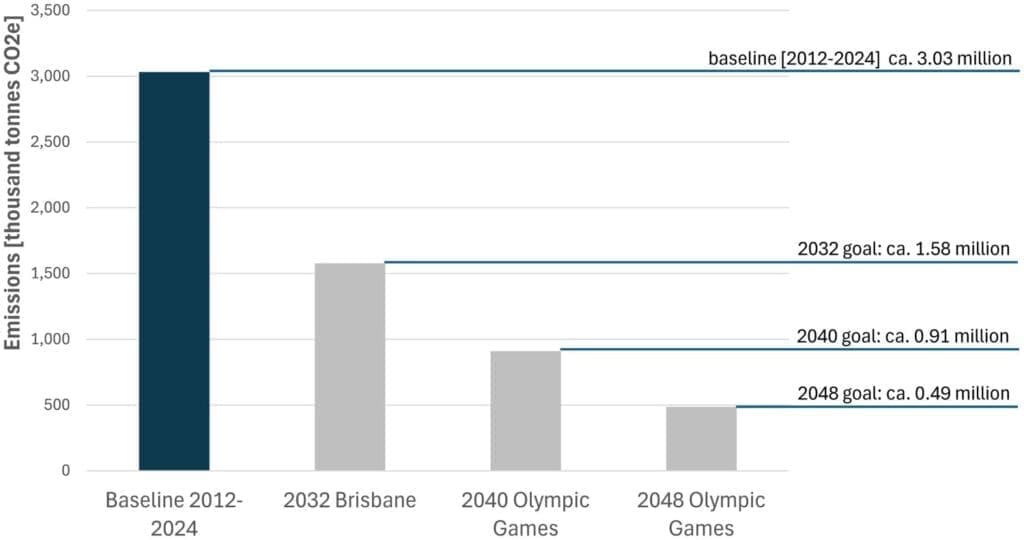

To remain consistent with the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting warming to 1.5 °C, the authors calculate that Olympic-related emissions would need to fall by 48% by 2030, 70% by 2040 and 84% by 2050. They argue that incremental efficiency gains will not be sufficient and call for structural changes, including scaling events to existing infrastructure, reducing air travel, expanding rail access and remote viewing options, increasing renewable energy use, and introducing independent emissions verification.

— Press Release —

Olympic Games and climate action: Time for a fundamental shift

As the world’s most-watched sporting event and through the emotions they generate, the Olympic Games could be a powerful lever for raising awareness of climate issues and accelerating the ecological transition.

As the Milan–Cortina athletes are about to step off the podium, the sustainability of these mega-events remains a central question. Although the Games have presented themselves in recent years as models of sustainability, they still have a massive carbon footprint, ranging from 1.59 to 4.5 million tonnes of CO₂e per edition since 2012.

A new study conducted by researchers from the University of Lausanne’s Faculty of Geosciences and Environment finds a gap between ambitious goals and reality, and argues that, to align with the Paris Agreement, Olympic emissions must be cut by 48% by 2030, 70% by 2040, and 84% by 2050. How can this be achieved? In their analysis, published in The Geographical Journal, the researchers outline concrete pathways for action, ranging from limiting the scale of events to reducing air travel, while preserving the spirit and soul of the Games.

Construction, travel, and renewable energy sources

At Rio 2016, the carbon footprint reached 4.5 million tonnes of CO₂e, roughly equivalent to the annual emissions of the city of Boston. The study highlights a critical paradox: while the Olympics are financially a media enterprise, their carbon intensity rivals that of the heavy construction and travel sectors. Paris 2024 marked a turning point by limiting its emissions to 1.59 million tonnes, thanks to a low-impact construction strategy (only two new competition venues) and optimized management of travel within the city. However, the study notes that despite these efforts, international spectator travel still accounted for nearly half of the total carbon footprint.

To meet the targets set by the Paris Agreement (limiting warming to +1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels), this momentum is still insufficient. Scientists call for a profound overhaul of the Olympic Games, going beyond technological advances and incremental adjustments.

To reduce the carbon footprint across all dimensions, the researchers argue that the Games should be scaled down to fit existing venues and transport systems. They also call for cutting air travel by prioritizing local spectators and sustainable rail travel and by developing immersive remote viewing options, such as virtual reality experiences, alongside partnerships with rail operators to improve access to fan zones. Finally, they recommend that event operations rely more heavily on renewable energy, plant-based catering, and low-carbon transport.

Revenue streams that remain largely untouched

These measures should not require a fundamental change to the Olympic Games’ economic model. They preserve the main revenue streams, which come primarily from broadcasting and sponsorship, with only a minor loss of ticketing income.

Independent oversight needed

The study also highlights one of the main obstacles to structural reform: a persistent lack of data collection and verification. For example, the IOC does not require any estimate of the carbon footprint during the bidding phase, nor independent verification of emissions once the Games are over, limiting transparency and the credibility of reported figures. The authors also recommend vetting the environmental credibility of major sponsors to mitigate the risk of greenwashing.

“Since 2020, the IOC has required host cities to reduce their emissions, but without providing a concrete roadmap, leaving the door open to purchasing carbon credits to claim a ‘neutral’ footprint, without changing practices and with a risk of greenwashing,” explains David Gogishvili, a researcher at the University of Lausanne and lead author of the study. “If the Olympic Games are to remain relevant in a world facing climate crisis, sustainability must go beyond rhetoric and become a binding, independently verified requirement,” he concludes.

Journal Reference:

Gogishvili, D., and M. Müller, ‘Past Carbon Emissions and Future Targets for the Olympic Games’, The Geographical Journal online ver., e70068 (2026). DOI: 10.1111/geoj.70068

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Laure-Anne Pessina | University of Lausanne (UNIL)

Featured image credit: Agzam Gaysin | Pixabay