A Falcon 9 rocket re-entry has led to the first direct ground-based detection of metal pollution nearly 100 kilometres above Earth, after scientists measured a concentrated plume of lithium in the upper atmosphere following the spacecraft’s descent.

In the early hours of 19 February 2025, the upper stage of a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket tumbled back through the atmosphere in an uncontrolled re-entry over the Atlantic Ocean, west of Ireland. The breakup produced a bright fireball that streaked across skies from the United Kingdom to Poland, drawing widespread attention.

“We were excited to try and test our equipment and hopefully measure the debris trail,” the research team led by Robin Wing and Gerd Baumgarten of the Leibniz Institute of Atmospheric Physics (IAP) told AFP via email.

Their results, published in Communications Earth & Environment, provide the first known direct detection of upper-atmospheric pollution caused by space debris re-entry.

Upper atmosphere lithium spike detected

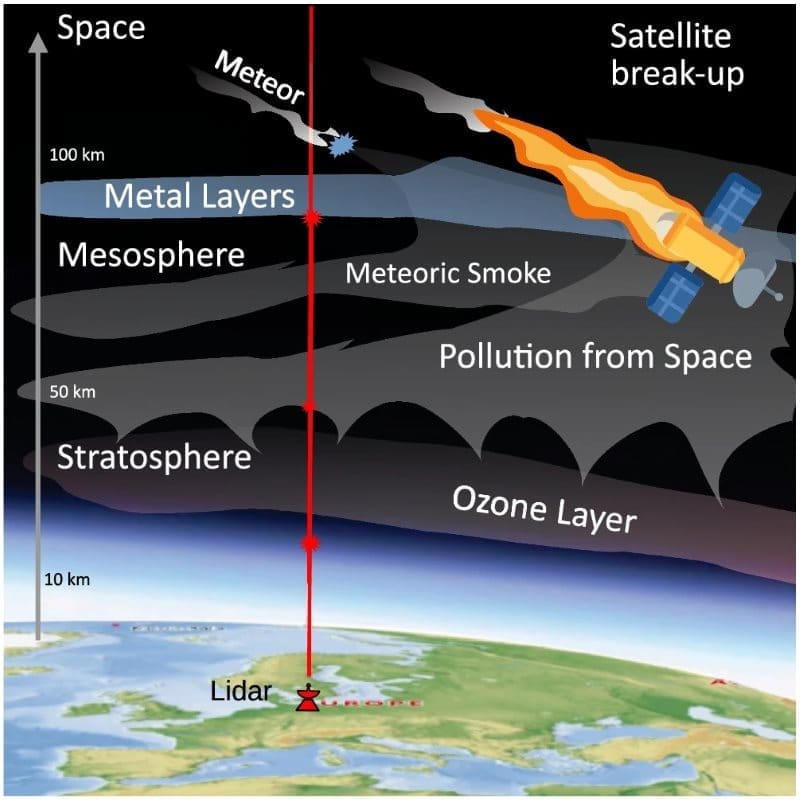

Using a resonance lidar system in northern Germany, the researchers monitored the lower thermosphere – a region between about 85 and 120 kilometres above sea level that is rarely measured directly from the ground. The instrument fires laser pulses into the sky and analyses the light that scatters back to identify specific atoms.

Shortly after 00:20 UTC on 20 February 2025, around 20 hours after the rocket’s descent, the team detected a well-defined lithium plume at roughly 96–97 kilometres altitude. Concentrations were about 10 times higher than typical background levels and extended down to about 94 kilometres. The signal remained visible for 27 minutes before observations ended.

Lithium is widely used in spacecraft components but occurs naturally only in trace amounts at these heights. By combining local wind data with atmospheric circulation models, the researchers traced the plume backward in time. The reconstructed air mass path aligned with the Falcon 9 upper stage’s re-entry trajectory west of Ireland. Additional modelling indicated that natural atmospheric processes were highly unlikely to explain the lithium increase.

The authors say the observations demonstrate that pollution from re-entering rockets can now be studied from the ground before it disperses.

Growing satellite fleets raise new concerns

Scientists refer to the region between 50 and 100 kilometres altitude as the “ignorosphere” because it is so difficult to study. Yet it plays a role in atmospheric chemistry and interacts with layers below.

“What we do know is that one ton of emissions at 75 kilometres (altitude) is equivalent to 100,000 tons at the surface,” the team told AFP, pointing to the potentially disproportionate impact of high-altitude releases.

Although the overall mass of human-made debris entering the atmosphere remains small compared with the steady influx of meteorites, its composition differs. Rockets and satellites contain metals and engineered compounds that are not typically found in natural space dust.

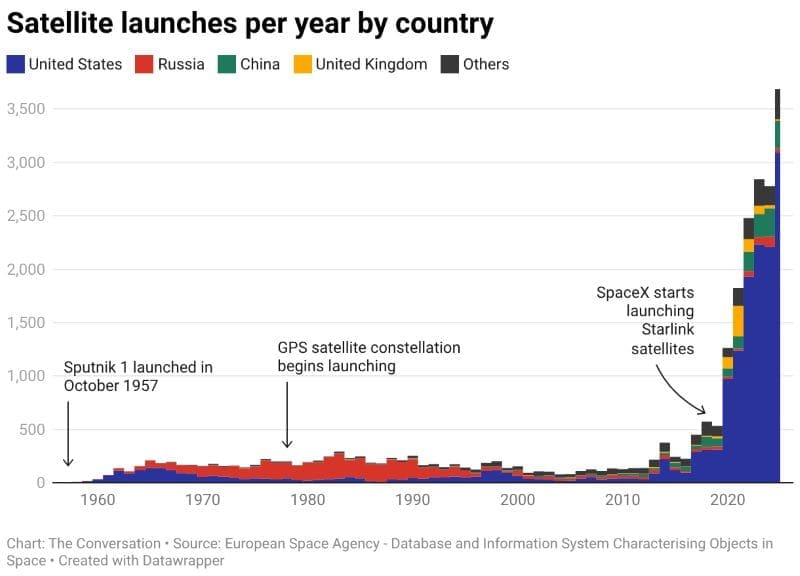

There are currently around 14,000 active satellites in orbit. SpaceX has proposed deploying up to 40,000 Starlink satellites, with an estimated total mass exceeding 10,000 tons, and other companies are pursuing large constellations. The study describes the observed lithium plume as a warning sign of the pollution that could follow as launch activity expands.

Regulation and long-term impacts unclear

The research focuses on a single re-entry event and does not quantify long-term effects. The authors note that not all materials released during atmospheric breakup can be detected in the same way, as chemical transformations occur during descent. They call for further measurements and atmospheric chemistry modelling to assess possible impacts on ozone and climate.

Eloise Marais, a professor of atmospheric chemistry at University College London who was not involved in the study, told AFP the research was “really important”.

“There is currently no suitable regulation targeting pollution input into the upper layers of the atmosphere,” she said, adding that changes in these remote regions could have wider consequences if they affect ozone in the layer that protects Earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation.

The findings establish a method to monitor metal pollution from rocket re-entries from the ground, at a time when the number of objects returning from orbit is expected to increase sharply.

Journal Reference:

Wing, R., Gerding, M., Plane, J.M.C. et al., ‘Measurement of a lithium plume from the uncontrolled re-entry of a Falcon 9 rocket’, Communications Earth & Environment 7, 161 (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-025-03154-8

Article Source:

Press Release/Materials: Daniel Lawler | AFP; Springer Nature

Featured image: SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket during the SAOCOM-1A mission night launch (2018). The article discusses the first direct detection of lithium pollution in the upper atmosphere linked to a Falcon 9 upper stage re-entry. Credit: SpaceX | Unsplash