Summary:

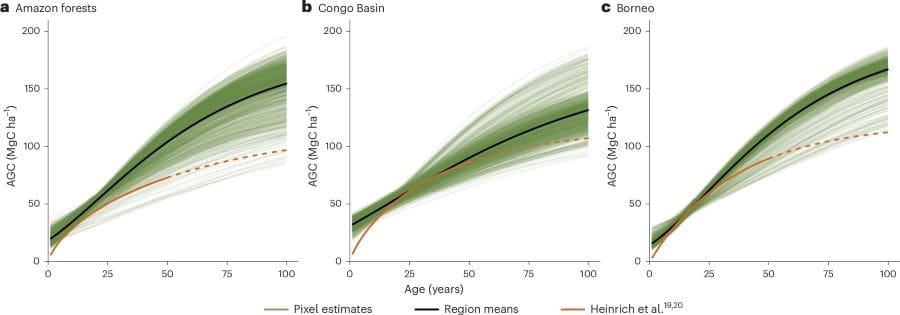

Young forests regrowing on previously deforested land could play a critical role in removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and slowing climate change, according to a new study published in Nature Climate Change. The international research team analyzed more than 109,000 field estimates of forest biomass alongside 66 environmental variables to generate high-resolution global maps of carbon uptake over the first 100 years of regrowth.

Their results show that forests aged between 20 and 40 years are particularly efficient at carbon removal – locking away up to eight times more carbon per hectare than newly regenerating forests.

These “young secondary forests,” which grow after land has been cleared of mature trees, were found to reach peak carbon removal rates earlier in tropical moist regions than in boreal or Mediterranean forests. The study suggests that protecting existing young forests may offer faster, more effective climate benefits than planting new ones.

If forest regeneration on 800 million hectares began in 2025, up to 20.3 billion metric tonnes of carbon could be removed by 2050 – but delays in action would significantly reduce this potential. The authors call for urgent updates to carbon market practices and climate policy to prioritize the preservation and management of these high-performing landscapes.

Young forests could help to capture carbon in climate change fight

Young forests regrowing from land where mature woodlands have been cut down have a key role to play in removing billions of tonnes of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) and combating climate change, a new study reveals.

To avoid severe global warming, large-scale removals of atmospheric carbon are needed. Forest regeneration offers a cost-effective method for carbon removal, but rates vary by location and forest age.

Researchers have discovered that young secondary forests, particularly those aged between 20 and 40 years, exhibit the highest rates of carbon removal – locking away up to eight times more carbon per hectare than newly regenerating forests.

Publishing their findings in Nature Climate Change an international team of scientists highlights several critical findings, including:

- Carbon removal rates vary significantly across different biomes and ecoregions, with tropical moist forests reaching their peak carbon removal capacity earlier than boreal and Mediterranean forests.

- Protecting existing young secondary forests offers immediate and substantial carbon removal benefits – delaying forest regeneration efforts reduces the potential for carbon sequestration.

Their study reveals that if 800 million hectares of restorable forest begin regenerating in 2025, up to 20.3 billion metric tonnes of carbon could be removed by 2050 but delays sharply reduce this potential.

Co-author Professor Adriane Esquivel-Muelbert, from the University of Birmingham, commented: “Our research underscores the critical role of young secondary forests in the global fight against climate change. The upcoming COP30 in Belém, Brazil presents a critical opportunity for world leaders to take decisive action.

“We urge policymakers to prioritise the protection and regeneration of young secondary forests as a key component of climate mitigation strategies. This can help us achieve faster and more substantial carbon removal, contributing significantly to global climate goals.”

Using a comprehensive dataset of more than 100,000 field estimates, researchers employed advanced random forest models to predict carbon densities in five-year age intervals, from five to 100 years – resulting in detailed global maps of carbon removal rates.

Co-author Dr Tom Pugh, from the University of Birmingham, commented: “Current carbon market methodologies often overlook the protection of very young secondary forests. This study highlights the need to revise these methodologies to credit the substantial carbon removal potential of these forests.”

Journal Reference:

Robinson, N., Drever, C.R., Gibbs, D.A. et al., ‘Protect young secondary forests for optimum carbon removal’, Nature Climate Change (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41558-025-02355-5

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Birmingham

Featured image credit: Ma_Frank | Pixabay