Summary:

Language used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) can influence how people interpret scientific agreement, according to new University of Essex research published in Nature Climate Change. The study examined how low-probability risks are framed in IPCC reports, which typically rely on negative terms such as “unlikely” or “the likelihood is low” for events with less than a 33 percent chance of occurring. Professor Marie Juanchich and colleagues found that these terms can lead people to infer division among scientists, even when expert agreement is strong.

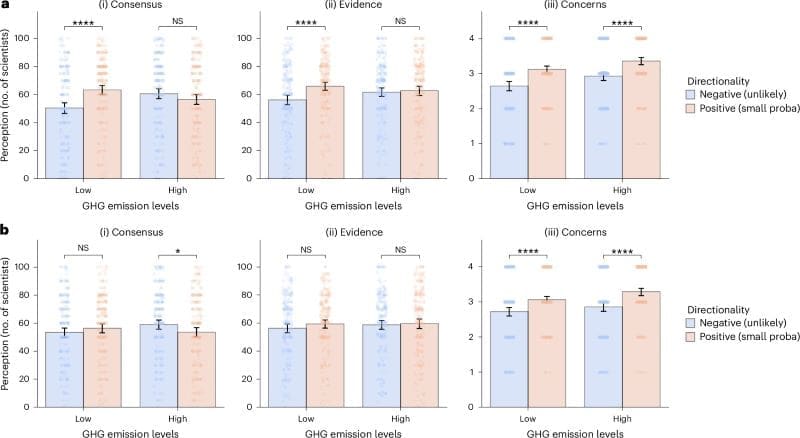

The research drew on eight experiments involving more than 4,000 UK residents. Participants often associated negative probability terms with fringe or doubtful claims, a pattern consistent with how these expressions appear in everyday conversation. The study reports that small wording changes, such as using “there is a small chance,” can shift attention toward why an outcome might happen and increase confidence in scientific assessments.

Professor Juanchich noted that many low-probability events can still have severe consequences. She also stressed the importance of communicating climate risks in a way that reflects the high standards of evidence behind IPCC assessments as discussions on global climate goals continue.

Public trust in science eroded by UN climate change language, study finds

The study of more than 4,000 UK residents found language used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) could make the public think scientists are divided and that predictions are extreme or implausible.

Created in 1988, the IPCC was established to provide policymakers with neutral regular scientific assessments on climate change, its implications, and potential future risks.

But Professor Marie Juanchich from the Department of Psychology found that the IPCC’s guidelines for communicating uncertainty may fuel scepticism.

The IPCC uses the term “unlikely” or “the likelihood is low” events like large magnitude sea level rise with a less than 33% chance of happening, which frames outcomes negatively.

Professor Juanchich found this was associated with fringe events and people tend to use terms like this in everyday conversation when disagreeing or doubting the truth of what they heard.

As a result, hearing “unlikely” led people to think climate scientists are divided, even when they are not.

This can make it easier for misinformation to spread, with the study finding that this crosses political orientations and beliefs in climate change.

Across eight experiments, Professor Juanchich found that small wording changes, such as using “there is a small chance,” focus attention on why something might happen and increase confidence in predictions.

Professor Juanchich said: “Although this is a simple change in wording, it can make a big difference as many low-probability events can still have severe impacts.

“A 20% chance of extreme sea-level rises, or extreme precipitation events is not something communities can afford to ignore.

“Yet calling these events ‘unlikely’ may make the public less aware of the risk and less willing to support actions that reduce or prepare for the threat of climate change.”

The research was published in Nature Climate Change just as COP30 finished in Brazil.

Politicians, diplomats, scientists, campaigners, and journalists met as global climate targets were scrutinised.

Professor Juanchich said: “The IPCC is providing a tremendous service to society by synthesising worldwide research on climate change to better inform climate action.

“It is important that insights covered in the reports are presented in a way that communicates their high scientific standards and climate scientists’ agreements on those estimates.

“We need to come together to address climate change, despite political divisions and rising populism currently dampening CO₂ reduction efforts. There is no planet B.”

Journal Reference:

Juanchich, M., Teigen, K.H., Shepherd, T.G. et al., ‘Negative verbal probabilities undermine communication of climate science’, Nature Climate Change (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41558-025-02472-1

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Essex (UoE)

Featured image credit: Pete Linforth | Pixabay