Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press roundup (December 5, 2025), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

The future fate of water in the Andes

In light of the ongoing fifteen-year megadrought in Chile, an international team of researchers, including Francesca Pellicciotti from the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA), addressed a bold future scenario. Their findings: by the end of the century, the considerably worn-out glaciers will not be able to buffer a similar megadrought. They call for coordinated global climate policies to develop effective water management strategies.

The results were published in Communications Earth & Environment.

Could a drought have no end? Fifteen years of severe and persistent drought in Chile have already passed, and the country seems left to bleed dry of its precious water resources. As surprising as this may sound, no one saw this coming. “Climate scientists only realized in 2015 that the unending drought in Chile was really a big thing,” says Francesca Pellicciotti, Professor at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA). “The Chilean megadrought was never forecast in any climate model. The existing models even showed absurd likelihoods for such an extreme event. And yet, it has happened and is still ongoing.”

In light of this evidence, a question emerges: Are we prepared for future climate disasters?

Now, Pellicciotti, together with Álvaro Ayala and Eduardo Muñoz-Castro, two Chilean Earth scientists now based at the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research WSL, sought to address this problem. With a team of international researchers, they modeled an audacious future scenario based on the ongoing Chilean megadrought. At the center of their analysis are glaciers in the Southern Andes, the majestic ‘water towers’ that are currently buffering the ongoing megadrought at the cost of their own survival.

‘Chile 2.0’ megadrought by 2100?

With the Atacama Desert in the north, Chile’s semiarid central region depends on snow for its water security. During droughts, glacier meltwater comes to the rescue. According to Ayala, Chileans were accustomed to recurrent droughts every five to six years, which would typically last for one or two years. “During the first few years of the current megadrought, people in Chile remained hopeful that things would improve the following year, and again the year after,” he says. But disillusionment would follow soon.

Perhaps all it takes to understand megadroughts is a bolder scientific approach. “Álvaro asked an elegant question: ‘What would happen if a similar megadrought struck Chile at the end of the century?’,” says Pellicciotti. “This simple, yet very clever question led to some really cool results.”

Half of today’s summer meltwater resources

In their model, the team focused on the 100 largest glaciers in the southern Andes (Central Chile and Argentina), accounting for seasonal snow and rain. They started by modeling 10 years before the onset of the drought and 10 years of megadrought. “We ensured we had a clear idea about the fate of glaciers, how much they lose mass, and what happens to the water,” says Ayala. “We then projected the model until the end of the 21st century, when the glaciers will be considerably smaller than now, and simulated a similar megadrought under these conditions.”

The scientists demonstrated that, in such a scenario, what will be left of the largest 100 glaciers in the Southern Andes will only be able to contribute half of today’s runoff meltwater during the dry summer months. For the smaller glaciers in the region, which were not included in this work, the situation might be even more dramatic. “The smaller glaciers will likely have disappeared by then, and a future ‘Chile 2.0’ megadrought will very likely be a severe blow for their ecosystems,” explains Ayala.

Megadroughts as the new normal?

Are these results realistic, considering that we did not even foresee the current megadrought in Chile? “There is a consensus that general models underestimate extremes,” says Pellicciotti. A recurrent pattern is that amid the general trend of global warming, episodic droughts occur as discrete severe events on a gradually worsening baseline, accompanied by continuous glacier mass loss. But while droughts are regular, megadroughts are quite unprecedented.

“In projections that consider very severe scenarios, we can indeed see megadroughts. However, in more moderate scenarios, the precipitation patterns are more similar to those we are experiencing today,” says Pellicciotti. “So, there must be something else that we don’t see in the models.”

Recently, Pellicciotti was involved in another study that reanalyzed global data collected over 40 years, confirming that multi-year extreme droughts will become more frequent, severe, and extensive. While this might forebode an age of megadroughts, scientists underline that it is still difficult to define them in the first place. Currently, megadroughts are labeled as such through their impact on vegetation. Even more strikingly, it becomes apparent during annual geosciences meetings that scientists still do not know what exactly causes megadroughts, Pellicciotti explains.

While the detailed mechanisms are still under investigation, researchers are increasingly warning that megadroughts have become the new normal and calling on policymakers to act accordingly. However, sometimes, the challenge remains to convince funding bodies of the need to research megadroughts on a global scale. “We started studying megadroughts in Europe because of the Chilean case,” says Pellicciotti. “However, reviewers were not always in favor of our efforts, arguing that there has been no megadrought in Europe since the Middle Ages. But then, a sequence of droughts hit Europe at an increasing frequency.”

Chile and Europe in one boat?

In Chile, the keyword “desertification” has become difficult to bypass. “We see this pattern slowly extending from the north toward the south. So, the deserts in the north likely show us today what central Chile might look like in the future,” says Ayala. “Similarly, in Europe, one can look at the Mediterranean mountains to understand the future of the Alps.”

In light of this, the researchers underline the need for coordinated global climate policies to develop effective water management strategies. While Chile has assigned priorities, Europe must still work with water managers to model scenarios on competing water uses and allocation programs. According to Pellicciotti, such scenarios must also account for megadroughts, meaning a system that is water-deficient from the start.

Thinking of their home country, Ayala and Muñoz-Castro also call for coordinated action. “We must be well prepared for what will come next, as we won’t be able to rely on all the factors that ‘worked’ until now during the current megadrought. We must be flexible enough with our water management plans to handle future situations without counting on the glacier’s contribution,” Ayala concludes.

Journal Reference:

Ayala, Á., Muñoz-Castro, E., Farinotti, D. et al., ‘Less water from glaciers during future megadroughts in the Southern Andes’, Communications Earth & Environment 6, 860 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-025-02845-6

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA)

Hidden in plain sight

Jiawei Bao still remembers coming home from middle school to catch the weather forecast on TV. It spanned from China’s northernmost province, Heilongjiang, to the southernmost province and tropical island, Hainan. In winter, the temperature between these regions can range from cold to balmy, varying by a staggering 50 degrees Celsius. “I was always fascinated by how such variations were predicted,” Bao recalls. This early curiosity led him to pursue a career in climate science.

Fast forward to 2025. Bao is now a postdoctoral researcher in Caroline Muller’s group at ISTA, where he uses physics and mathematics to address fundamental questions in climate science. He aims to understand climate processes and their societal consequences.

Bao has now identified a new type of oscillation in the tropics. The tropics-wide intraseasonal oscillation, or simply TWISO, is a repeating pattern that manifests itself over several weeks in tropical regions with rainfall, clouds, and wind. Together with Muller, Sandrine Bony from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) at France’s Sorbonne University, and Daisuke Takasuka from Japan’s Tohoku University, he published the findings in the journal PNAS.

The ABCs of atmospheric circulation

Changes in the large-scale atmospheric circulations form an essential component of this newly identified oscillation. While atmospheric circulations and oscillations are complex, they influence our daily lives in the form of wind, weather fluctuations, and seasonal changes. In extreme cases, their impact becomes apparent in tropical storms, such as hurricanes, typhoons, and cyclones. These storms can have devastating effects, as shown by several recent examples – Hurricane Melissa in the Caribbean and typhoon Kalmaegi, which caused severe damage and fatalities in the Philippines before hitting Vietnam.

“Atmospheric circulation refers to the large-scale movement of air that redistributes energy, momentum, and mass from one specific location to another,” explains Bao. In tropical regions, he notes, the Hadley circulation is the primary north-south circulation pattern. It features rising air at the equator and sinking air in the subtropics. By contrast, the Walker circulation is the dominant west-east circulation pattern in the equatorial Pacific, with rising air over the western Pacific and the Maritime Continent (Indonesia, Malaysia, and Pacific islands), and sinking air over the eastern Pacific.

Oscillation as a giant pendulum

Besides atmospheric circulations, climate oscillations also play a crucial role in the climate of tropical regions. Oscillations are fluctuations of climate systems, ranging in duration from a couple of weeks to even millennia. “An oscillation is like a giant pendulum that swings back and forth. When it swings one way, it might bring warmer and wetter conditions. When it swings the other way, it could bring cooler and drier weather,” Bao explains.

Oscillations often trigger extreme weather conditions. A prime example is the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, which oscillates over timescales of two to seven years and causes extreme weather in various parts of the globe during its different phases.

Bao and his colleagues have now detected a new oscillation system called “tropics-wide intraseasonal oscillation.” Dubbed TWISO, it is an oscillation that has always been present but that went unrecognized – until now.

TWISO: Long present, newly identified

The scientists identified TWISO using satellite observations and the reanalysis of datasets, developed and maintained by leading research institutions and shared openly with the global scientific community.

For example, Bao used the ERA5 dataset, provided by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). It represents the fifth generation of global climate and weather reanalysis dating back to 1940. Additionally, data satellite observation data from NASA’s Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy System (CERES) contributed to the findings.

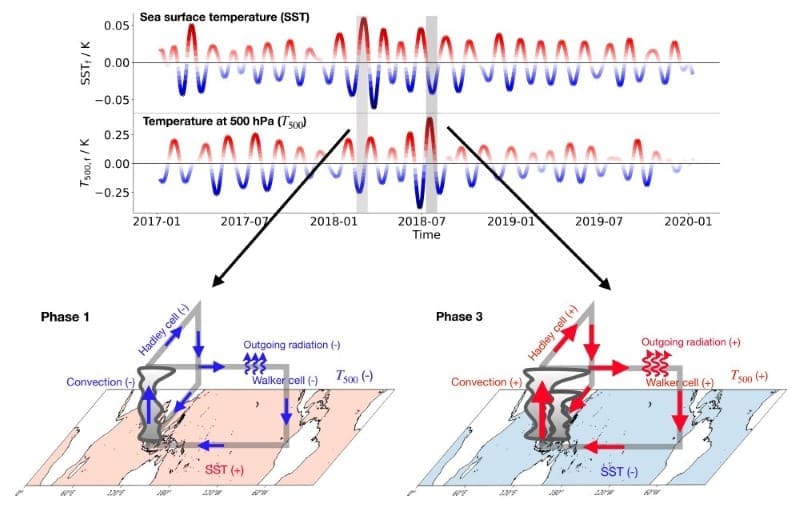

“TWISO is a natural phenomenon that has always been present but it was only recently identified in our paper through analysis of historical observations and reanalysis data,” Bao says. “The defining feature of TWISO is its tropics-wide coherence. It represents a large-scale oscillation encompassing the entire tropical belt, with variations occurring on intraseasonal timescales of about 30 to 60 days.”

The tropical atmosphere’s pulse

During each oscillation cycle, different components of the tropical climate system, including atmospheric temperature, ocean surface temperature, winds, and radiation, vary in a synchronized manner. In that sense, TWISO can be viewed as the “pulse” of the tropical atmosphere.

One of TWISO’s main elements is the variation of convection – the process by which heat is transferred through a fluid – over the “warm pool.” The warm pool is a region covering the western Pacific and the Maritime Continent where sea surface temperatures are the highest on Earth. It is a hotspot of intense and persistent thunderstorms that tightly link the ocean and atmosphere.

“We found that convection in this region goes through strong cycles of intensification and weakening, which play a central role in setting the rhythm for the entire tropical climate system to oscillate together,” says Bao.

Basis for better weather forecasts?

Bao and his colleagues note that the effects of TWISO on regional weather are still uncertain. Like other oscillations, TWISO represents a deviation of the normal state, which can often lead to extreme weather events. Bao highlights that during a specific phase of TWISO, sea surface temperatures increase, raising the likelihood of cyclone formation.

Given the annual threats posed by tropical storms, accurate weather forecasting is crucial for saving lives and livelihoods, planning evacuations, and preparing disaster responses. Nonetheless, predicting tropical weather one to two months in advance remains a major challenge. Since TWISO follows consistent patterns over 30 to 60 days, it presents an opportunity to enhance predictability within this timescale.

“By understanding TWISO, we could improve our ability to predict when tropical cyclones are likely to form, allowing us to issue earlier warnings and help to minimize the risks and damage they cause. We plan to address this in future research,” Bao says.

Journal Reference:

J. Bao, S. Bony, D. Takasuka, & C. Muller, ‘Tropics-wide intraseasonal oscillations’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A. 122 (48) e2511549122 (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2511549122

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA)

Researchers find promising adaptations to climate change in tropical forests

As tropical forests experience chronic drying and more extreme droughts due to climate change, some plants are adapting by growing longer root systems to reach water deep within soils, according to a study published in New Phytologist. Research led by Colorado State University Professor Daniela Cusack and Ph.D. student Amanda Longhi Cordeiro found that tropical forest roots demonstrate flexibility under drying conditions, which may help reduce vulnerability to drought.

“This finding shows that even while tropical forest roots in surface soils die off under drought, representing a carbon loss to the forest, some trees are able to send roots deeper in search of moisture, potentially helping rescue the forest,” Cusack said. “How extensive this rescue effect might be is unknown, and the increase in deeper roots is not enough biomass to offset carbon losses from much more extensive root death in the surface soils.”

Home to some of the largest stores of carbon on Earth, tropical forests help prevent the severe effects of climate change; however, as rainfall decreases, carbon storage – in addition to ecosystem function and root dynamics – could change. To better understand these effects, CSU researchers have been studying root systems in tropical forests during drought.

Cusack’s team examined how drying soils influence roots and their resource acquisition in four lowland tropical forests across Panama. The long-term implications for soil carbon storage and forest resilience remain uncertain, emphasizing the need for extended studies across various tropical forest ecosystems.

Journal Reference:

Cordeiro, A.L., Cusack, D.F., Dietterich, L.H., Valdes, E., Gonçalves, N.B., Oliveira, M., Quesada-Ávila, G. and Wright, S.J., ‘Drying suppresses fine root production to 1 m depths and alters root traits in four distinct tropical forests’, New Phytologist (2025). DOI: 10.1111/nph.70751

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Monica McQuail | Colorado State University (CSU)

New research highlights the need for region-responsive conservation planning over universal frameworks

Pollinators, including bees, butterflies, and beetles, shape global food production and support vast natural ecosystems. For years, efforts to protect these critical species have leaned on broad global targets and uniform conservation recommendations. However, a new study led by researchers at the Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar (IITGN) and Northeastern University, USA, demonstrates that such generalised approaches may not have the desired impact, and in some regions, could offer imperceptible benefit.

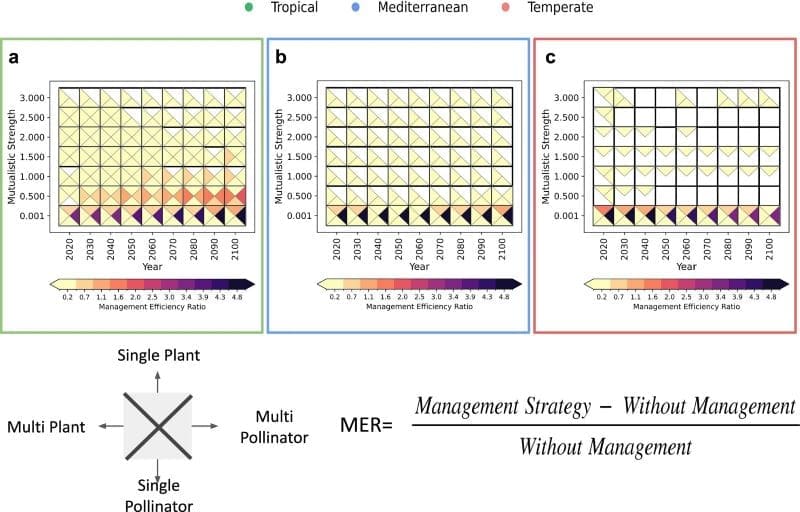

The research, published recently in Communications Earth & Environment, highlights how climate change affects pollination systems differently across the tropics, Mediterranean, and temperate zones. It also emphasises the need to develop adaptive conservation strategies that are tailored to the ecological context and do not follow a one-size-fits-all format.

Speaking about their research, Dr Udit Bhatia, an Associate Professor at IITGN’s Department of Civil Engineering and the principal investigator of the study, said: “Unlike most research that examines how climate change affects individual species, we have attempted to map entire ecological networks from diverse regions.”

The team analysed eleven real-world networks of plants and pollinators from tropical, temperate, and Mediterranean regions and observed their responses to increasing temperatures. By combining network information with climate projections from multiple Earth System Models, they investigated how rising temperatures could alter growth rates, mortality, competition, and the strength of mutual relationships between species over the next 75 years.

“Our results indicated that tropical networks, home to some of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems, showed the greatest vulnerability,” said Ms Adrija Datta, first author of the study and a PhD scholar in IITGN’s Department of Earth Sciences. The team ran simulations, which indicated a sharp reduction in pollinator populations with rising temperatures, with several networks losing stability. Even moderate warming substantially reduced pollinator abundance in these systems, increasing dependence on a few dominant species.

Many species in these regions already function near their upper thermal limits, meaning even slight temperature increases can push them beyond physiological tolerance. Mediterranean networks also showed steep declines, driven by intense summer heat and sharp seasonal fluctuations. By contrast, temperate ecosystems, such as those found in much of Europe and North America, exhibited comparatively slower declines, primarily because species in these regions experience broad seasonal temperature ranges and maintain wider thermal safety margins.

However, the study notes that the relative stability of the temperate ecosystem does not imply long-term safety. “Despite the ecosystem being relatively balanced, the inclusion of other pollinator threats, such as habitat loss, pesticide exposure, and timing mismatches between plants and pollinators, could accelerate decline,” added Mr Sarth Dubey, co-author and a PhD scholar in IITGN’s Department of Computer Science and Engineering. These results indicate the necessity of developing region-specific conservation efforts to maximise biodiversity protection.

To test whether such targeted interventions could be effective, the team evaluated two strategies: protecting a single influential species and supporting multiple highly connected species. In tropical networks, restoring multiple keystone species enhanced pollinator abundance and community balance, thereby increasing network resilience. However, the same strategy yielded minimal change in Mediterranean and temperate systems. “Management works in the tropics because there are species whose presence and abundance hold the network together,” explained Ms Datta. “That kind of leverage does not exist everywhere.”

The findings reinforce that conservation cannot be exported wholesale from one region to another. Scientists, policymakers and conservation planners need to develop strategies that reflect biology, climate exposure, and the structure of species interactions. “Climate adaptation policies are being negotiated worldwide, but ecological responses are not universal,” said Mr Dubey. The study provides a scientific basis for prioritising where action is most urgent, and where ecosystems may have built-in capacity to cope.

As the next step, the researchers plan to integrate additional pressures such as land-use change, chemical exposure, and fragmentation to build a more comprehensive risk model. According to Dr Bhatia, understanding how these combined stresses may reshape networks, particularly in regions currently considered stable, will be critical for long-term conservation planning.

Journal Reference:

Datta, A., Dubey, S., Gouhier, T.C. et al., ‘Warming demands extensive tropical but minimal temperate management in plant-pollinator networks’, Communications Earth & Environment 6, 969 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-025-02924-8

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar (IITG)

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay