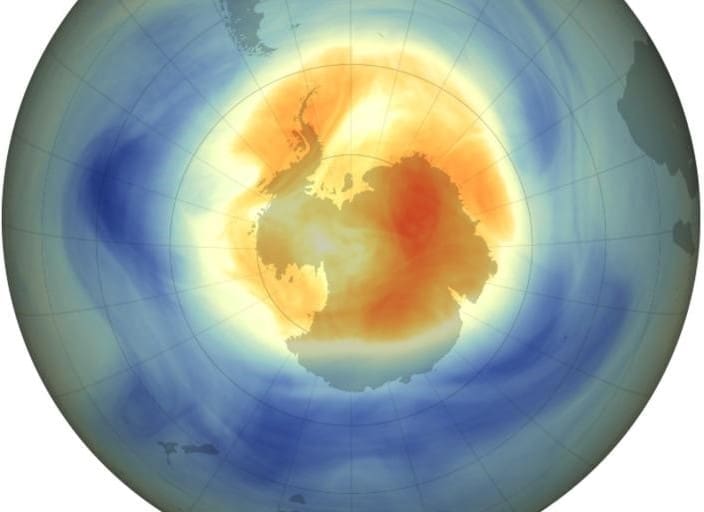

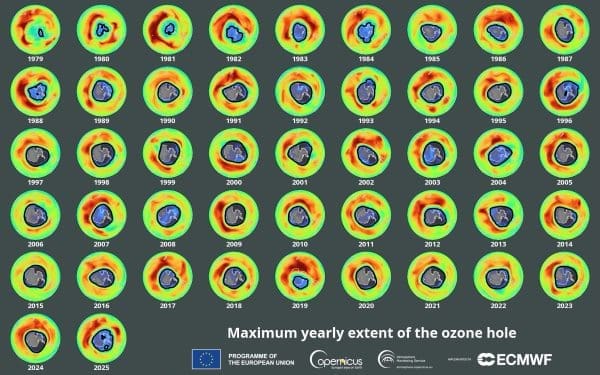

The 2025 Antarctic ozone hole closed on 1 December, earlier than in any year since 2019, and stood out as both smaller and shorter-lived than most ozone holes observed over the past decade. The early closure adds to a growing body of evidence that Earth’s protective ozone layer is continuing a slow but steady recovery after decades of damage from ozone-depleting chemicals.

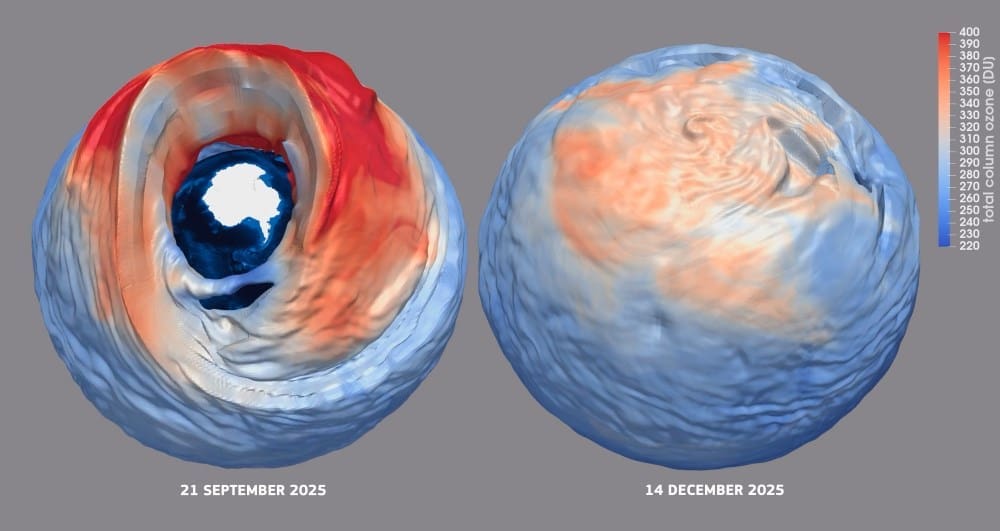

During the austral spring, when the ozone hole typically forms and expands over Antarctica, 2025 depletion followed a familiar seasonal pattern at first. The hole grew rapidly through August and September, reaching its maximum extent around 21 September. At its peak, it covered close to 20 million km², remaining relatively large through October before beginning an unusually rapid contraction in November.

By early December, only a small area of low ozone remained, and on 1 December the hole was considered fully closed. Over the past 40 years, such an early end has been rare, placing 2025 among the earliest closures on record. Scientists also noted higher ozone concentrations than in many recent years, reinforcing expectations that long-term recovery is underway.

Montreal Protocol

In numerical terms, the 2025 ozone hole ranks as the fifth smallest observed since 1992, the year when the Montreal Protocol began to take effect. Data from NASA and NOAA show that during the core of the ozone-hole season, from 7 September to 13 October, the average extent was about 18.71 million km². That is roughly 30% smaller than the largest ozone hole ever recorded, in 2006, and the breakup occurred nearly three weeks earlier than the average over the past decade.

Each year, the size and duration of the Antarctic ozone hole depend on a combination of atmospheric conditions and chemistry. Temperatures and wind patterns in the stratosphere over the Southern Hemisphere play a major role, as does the remaining presence of human-emitted ozone-depleting substances. While year-to-year variability remains a defining feature of the phenomenon, the overall trend since the early 2000s has been one of gradual improvement.

The visualisation shown here was produced using data from the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS). It presents a three-dimensional rendering of the ozone hole over Antarctica, highlighting two moments in the 2025 season. One view shows the maximum extent reached on 21 September, when ozone depletion was at its most pronounced. The second depicts conditions on 12 December, after the hole had already closed.

Scientists emphasise that the encouraging signs seen in 2025 are closely linked to international action taken decades ago. The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, adopted in 1987 and now universally ratified, phased out the production and use of chemicals once common in refrigeration, air conditioning, firefighting foams and aerosol products. Since the protocol came into force, concentrations of ozone-depleting substances in the Antarctic stratosphere have fallen by about one third from their peak around the year 2000.

Paolo Laj, Chief of the World Meteorological Organization’s Atmospheric and Environment Research Section, said: “We are obviously aware that there is year-to-year variability in the ozone hole associated with atmospheric dynamics. But our scientific monitoring confirms our predictions that the ozone layer is well on track to recovery thanks to the Montreal Protocol and its phase out of the vast majority of ozone depleting chemicals which were once used in refrigeration, air conditioning, firefighting foam and even hairspray.”

Laj also stressed the broader implications of continued recovery. “We are confident that the ozone layer can return to 1980s levels by the middle of this century, significantly reducing risks of skin cancer, cataracts, and ecosystem damage due to excessive UV exposure. But we must avoid complacency and continued scientific monitoring is essential,” he said.

Independent analyses point to the same conclusion. Stephen Montzka, a senior scientist with NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory, noted that without reductions in chlorine levels, this year’s ozone hole would have been substantially larger. NASA scientist Paul Newman added: “This year’s hole would have been more than one million square miles larger if there was still as much chlorine in the stratosphere as there was 25 years ago.”

CAMS director Laurence Rouil described the 2025 season as a reminder of what coordinated global action can achieve. “The earlier closure and relatively small size of this year’s ozone hole is a reassuring sign and reflects the steady year-on-year progress we are now observing in the recovery of the ozone layer thanks to the ODS ban. This progress should be celebrated as a timely reminder of what can be achieved when the international community works together to address global environmental challenges,” he said.

According to the most recent assesment co-sponsored by the WMO and the UN Environment Programme project that, if current policies remain in place, the ozone layer will return to pre-1980 values by around 2066 over Antarctica, by 2045 over the Arctic and by 2040 for the rest of the world. The next major scientific assessment is due in 2026. For now, the smallest and shortest-lived ozone hole in five years offers a clear visual signal that the long recovery process is continuing.

Featured image credit: European Union, Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service Data