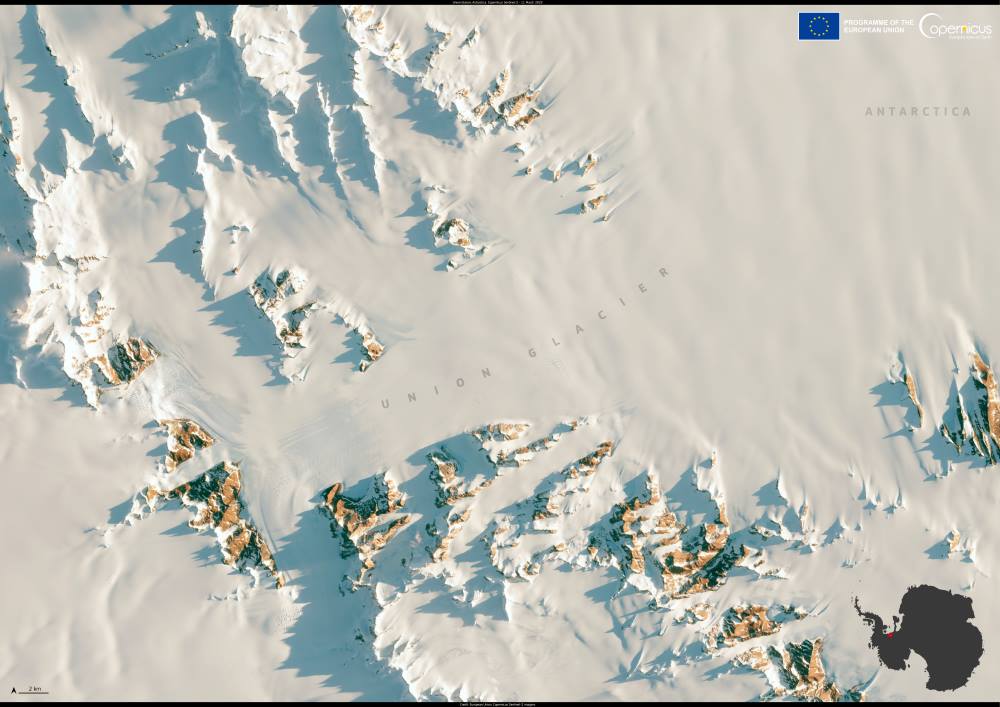

In the remote expanse of West Antarctica, Union Glacier cuts a path through the Ellsworth Mountains — its brilliant white surface, scarred with crevasses, betraying the immense pressure and movement beneath. Captured by the Copernicus Sentinel-2 satellite on 11 March 2025, this image reveals a landscape both stark and vulnerable, offering a powerful symbol of the rapid changes reshaping our planet’s southernmost continent.

Once considered relatively stable due to its inland location and consistently sub-zero temperatures, Union Glacier is now showing signs of strain. Recent research has revealed that between 2022 and 2024, the world experienced the largest three-year loss of glacier mass ever recorded. This dramatic loss is largely attributed to global heating, with warming ocean currents and atmospheric temperatures pushing farther inland than ever before. In areas like West Antarctica, that means even glaciers well away from the coast, like Union, are being destabilized.

A sentinel in a warming Antarctica

Despite its location in one of the coldest and driest regions on Earth, Union Glacier is not immune to these changes. Researchers now believe that parts of the glacier could be approaching a climatic tipping point. Although it still remains below freezing, warming trends are infiltrating this high-elevation zone, threatening to disrupt long-term ice stability. Once such thresholds are crossed, glacier retreat may become irreversible — leading to faster ice discharge into the ocean and a significant rise in global sea levels.

Glaciologist Dr. Ricardo Jaña of the Chilean Antarctic Institute, who has studied Union Glacier for over a decade, warned that the encroachment of warm air and water from the coast represents “a creeping risk” to inland ice. This inland warming, once thought unlikely, is now being observed across several West Antarctic sites.

The consequences go far beyond the continent itself. Antarctica holds enough frozen water to raise sea levels by nearly 60 meters if fully melted. While complete loss is not imminent, the region’s accelerating ice melt is already contributing to measurable sea level rise. Between 2012 and 2017, Antarctica lost an estimated 219 billion tonnes of ice annually — three times more than it lost per year from 1992 to 2001. And as glaciers like Union begin to shift and break down, that contribution could increase.

Even more concerning is the potential for these changes to disrupt ocean circulation systems. The influx of freshwater into the Southern Ocean can interfere with the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), a system of currents that regulates temperature and weather patterns across the Northern Hemisphere. Disruption to the AMOC could lead to cooler conditions in Europe, shifting rainfall belts in the tropics, and more intense storms along North Atlantic coasts.

Tools like the Copernicus Sentinel satellites are crucial in monitoring these changes. By providing high-resolution images and data on ice flow, temperature, and melting patterns, they help researchers detect early warning signs of ice loss and assess the global impacts of regional climate shifts. This data feeds directly into climate models, helping policymakers make informed decisions on mitigation and adaptation.

Union Glacier may seem distant from everyday life, but what happens in Antarctica does not stay in Antarctica. As glaciers melt and oceans respond, coastlines, agriculture, and infrastructure thousands of kilometers away are affected. The transformation underway at Union Glacier is a clear sign of a warming planet — and a reminder that global action on climate is not only urgent, but unavoidable.

Featured image credit: European Union, Copernicus Sentinel-2 imagery