Summary:

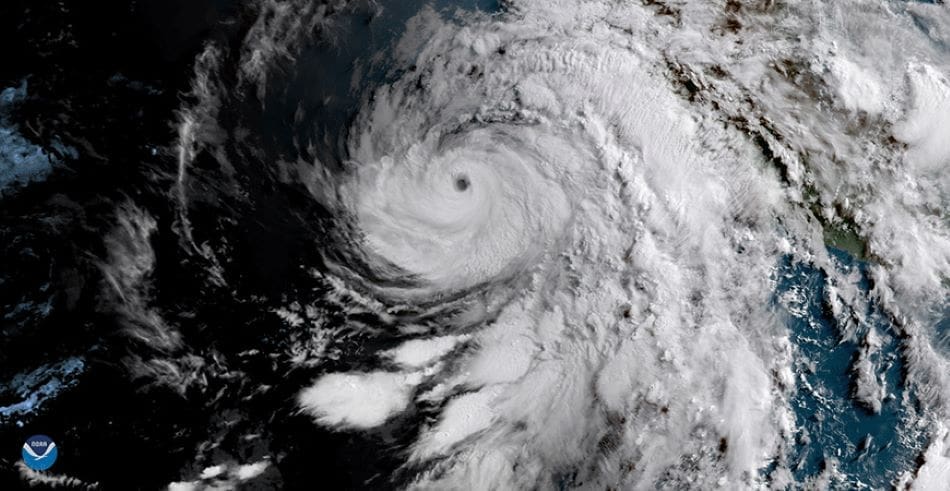

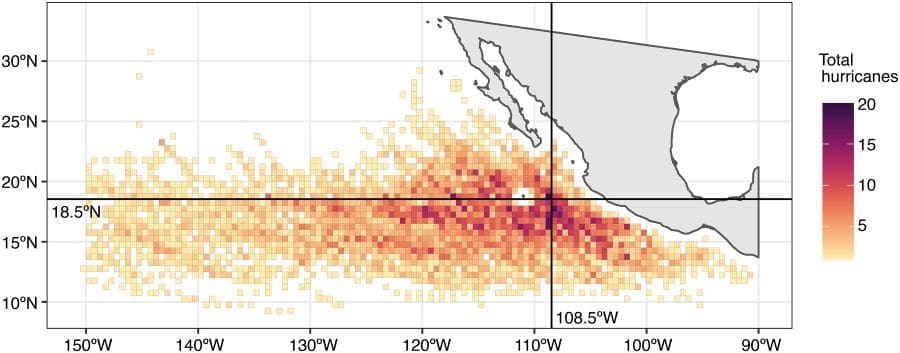

A rare opportunity to sample ocean waters just after a major hurricane has revealed how tropical cyclones can dramatically disrupt deep-sea chemistry and marine ecosystems. In a study published in Science Advances, researchers report that Hurricane Bud, a Category 4 storm that swept through the eastern tropical North Pacific in 2018, caused striking biogeochemical changes beneath the ocean surface.

The team, led by marine biologist Michael Beman and colleagues from UC Merced, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, documented how the hurricane triggered a rapid rise of the ocean’s largest oxygen minimum zone (OMZ), shoaling it by up to 50 meters. This exposed shallower waters to low-oxygen conditions that are typically confined to much deeper layers.

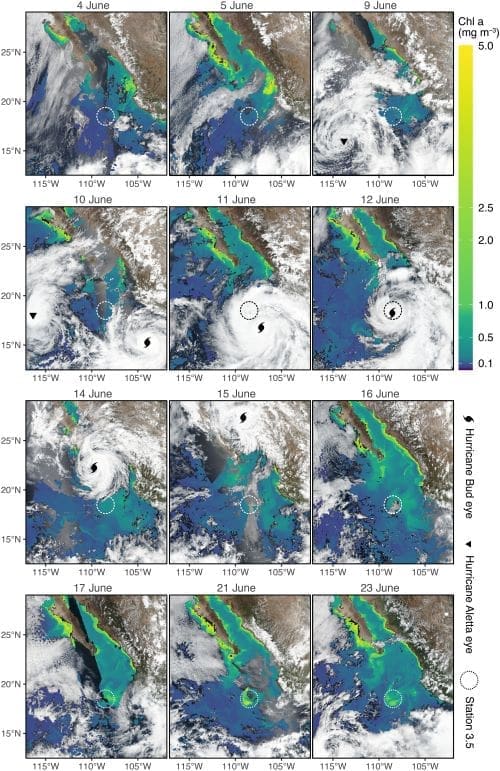

At the same time, the storm spurred a surge in phytoplankton growth visible from space, supporting blooms of bacteria and marine life. Organic matter analysis and RNA sequencing revealed an explosion of microbial activity, with surface layers dominated by phytoplankton degraders and deeper zones by anaerobic bacteria. “These hurricane-generated blooms are like oases for ocean organisms,” said Beman.

The research offers new insight into how increasingly intense storms may shape ocean biology and carbon cycling in a warming world.

Hurricanes create powerful changes deep in the ocean, study reveals

The team was able to sample the ocean right after the storm passed and found that the storms churn the ocean so powerfully and deeply — up to thousands of meters — that nutrient-rich, cold water is brought to the surface.

The resulting phytoplankton blooms — visible in satellite imagery taken from space — are a feast for bacteria, zooplankton, small fish, and filter-feeding animals such as shellfish and baleen whales.

“When we got there, you could actually see and smell the difference in the ocean,” said Professor Michael Beman. “It was green from all the chlorophyll being produced. There were totally different organisms there, and they were going nuts in the wake of the storm.”

But all that mixing also stirs up low-oxygen zones deep in the water, bringing them much nearer the surface than usual, threatening organisms that need higher oxygen concentrations to survive.

Beman, a marine biologist, studies microbial ecology and biogeochemistry. One of his focuses is oceanic oxygen minimum zones (OMZs), large and globally significant areas with little to no oxygen. They are persistent layers in the water column that have low oxygen concentration due to biological, chemical and physical processes. OMZs occur naturally, in contrast to similar “dead zones” that pollution can produce.

OMZs are typically found at mid-depths and can significantly impact marine ecosystems as they are inhospitable to many organisms. Warming ocean waters are contributing to the expansion of OMZs.

In 2018, Beman and his lab went on a research expedition from Mazatlán, Mexico, to San Diego, to study OMZs with collaborators from Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and several other institutions.

They knew turbulent weather was likely and closely watched as the second named storm of the year, Hurricane Bud, spun into their planned sampling region.

“We were very careful, and we had plans A, B, C and D in place,” he said. “The forecasting was extremely accurate, and we knew the storm rapidly intensified.”

Instead of going ashore, they traveled between research sites and behind islands while they waited for the storm to pass.

“There was some skill involved, but definitely some luck, too, and we ended up adding a sampling location right where the storm was at maximum power,” Beman said, “basically within a few kilometers of the former eye.”

Those samples are rarely, if ever, taken just after a hurricane has churned the water so powerfully. The data indicated the hurricane had dramatically changed oxygen concentrations.

“I’ve never seen measurements like that in those areas of the ocean, ever,” Beman said.

Since the trip, the researchers have been examining different aspects of the results, and a new paper in Science Advances, a journal published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, details their findings.

Beman collaborated on the expedition with Scripps geosciences Professor Lihini Aluwihare and two of her students, Margot White and Irina Koester.

“Margot noticed the subsurface changes from the hurricane when she was preparing her thesis chapters, especially the fact that the oxygen minimum zone had rapidly shoaled,” he said. “Irina searched her unique organic matter data to look for changes driven by the hurricane, which turned out to be very clear and dramatic.

“We’ve met many, many times to analyze the data and figure out what effects the hurricane had and why.”

The samples also included DNA and RNA, so the researchers could detect the signatures of the organisms that responded to the phytoplankton bloom. Beman said they saw many turtles, which was unusual because they were so far offshore.

“We were doing this at a time of year when there’s not a lot going on biologically in these areas of the ocean,” he said, “so these hurricane-generated blooms are like oases for ocean organisms. We detected a bacteria bloom, but I wouldn’t be surprised if larger organisms made use of the hurricanes. They might sense the storms coming and then migrate to areas the storm had just passed over.”

Their samples and data are so unique that Beman plans to keep working on them and hopes to collaborate with other scientists interested in the effects of hurricanes and hurricane forecasting.

“We are just scratching the surface of what these storms do, and it was a rough few days at sea,” he said. “I hope we continue to learn as much as we can about what actually happens during and after hurricanes.”

Journal Reference:

Brandon M. Genco et al., ‘Tropical cyclones drive oxygen minimum zone shoaling and simultaneously alter organic matter production’, Science Advances 11, 23: eado8335 (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ado8335

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Lorena Anderson | University of California – Merced (UC Merced)

Featured image : Hurricane Bud, shown here over Baja in 2018, extended across Mexico and left some surprising changes in its wake, UC Merced researchers found. Credit: NOAA