Summary:

Emperor penguins may be vanishing from Antarctica more quickly than previously feared, according to a new study published in Communications Earth & Environment. Using very high-resolution satellite imagery, researchers from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) assessed penguin numbers across a key region covering roughly 30% of the species’ global population. Between 2009 and 2024, the population in this area — which spans the Antarctic Peninsula, Weddell Sea, and Bellingshausen Sea — is estimated to have declined by 22%. That equates to an average loss of 1.6% each year and is significantly steeper than earlier estimates and even some of the worst-case projections for this century.

“This new count isn’t necessarily symbolic of the rest of the continent,” said Dr Peter Fretwell of BAS, “but if it is – that’s worrying because the decline is worse than the worst-case projections we have for emperors this century.”

The findings raise fresh concern for a species already considered highly vulnerable to climate change. Emperor penguins rely on stable sea ice for breeding, but that ice is increasingly unreliable due to warming oceans and shifting weather patterns. Researchers are now working to extend their satellite survey to the rest of Antarctica to determine if the trend holds continent-wide.

Emperor penguin populations in Antarctica declining faster than thought

A new analysis of up-to-date satellite imagery suggests the birds’ numbers declined 22% over a 15-year period (2009 to 2024) in a key sector of the continent – encompassing the Antarctic Peninsula, Weddell Sea and Bellingshausen Sea. This compares with an earlier estimate (2009 and 2018) of a 9.5% reduction across Antarctica as a whole. Experts at the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) are now checking to see whether their latest assessment in the narrower geographic range reflects the same story across Antarctica.

Dr Peter Fretwell, who studies wildlife from space at BAS, says: “There’s quite a bit of uncertainty in this type of work and what we’ve seen in this new count isn’t necessarily symbolic of the rest of the continent. But if it is – that’s worrying because the decline is worse than the worst-case projections we have for emperors this century.”

Those computer modelled projections point to the species approaching extinction by 2100, assuming current rates of global warming continue and are maintained.

A rapidly warming climate poses a particular challenge for emperor penguins because of their dependence on seasonal sea-ice. The species uses the frozen sea ice around the Antarctic coastline as a platform on which to mate and bring up their young. This ice needs to be stable for about eight or nine months of the year. Unfortunately, the recent trend has seen sea ice in many parts of the continent become patchy and unreliable, likely harming breeding success.

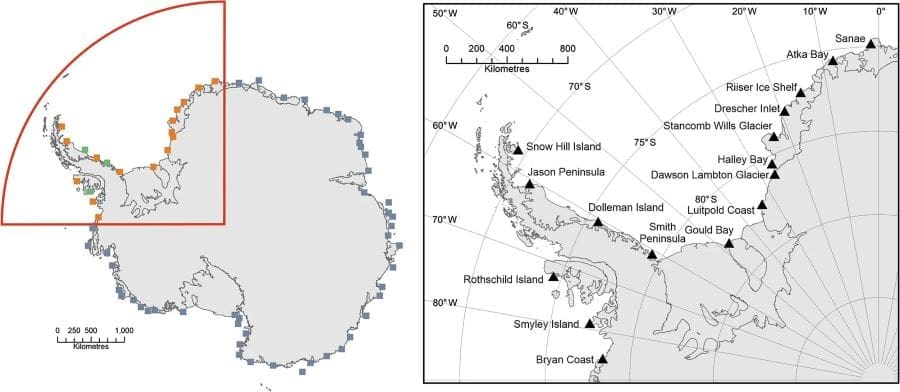

The last global census of emperors found the total population had declined by 9.5%. It covered the 10 years up to 2018, and included what appeared to be a slight uptick in numbers towards the end of the period. The latest work extends the count up to 2024, but does so only for the limited area running between 0 degrees to 90 degrees West longitude – from Dronning Maud Land to the Bellingshausen Sea, taking in the entire Antarctic Peninsula. The quadrant, which at 2.8 million square kilometres is more than 11 times the size of the UK, is significant as it contains about 30% of the global emperor population.

In this narrower geographic range, the team finds the decline in the number of birds continues through the extended time period, equating to an average reduction of 1.6% per year, or 22% over the full 15 years.

Counting penguins from space is not straightforward and relies on estimating the number of individuals in the large huddles of birds detected in high-resolution satellite imagery. The approach is however, the only way scientists can really gauge the emperors’ status because many of the breeding sites are so remote they would be extremely difficult, even dangerous, to reach in person.

A collection of satellite pictures is now being assembled to update the global population of emperors.

The report highlights the complex interplay of climate-related factors beyond just unreliable sea-ice conditions that appear to be making life harder for the penguins. These include changing storm, snow and rainfall patterns; increased competition for food resources as other wildlife shift their ranges; and the increased disturbance and predation coming from petrels, seals and killer whales, which are exploiting a more open ocean.

Dr Phil Trathan, co-author and emeritus fellow at BAS, says: “The fact that we’re moving to a position faster than the computer models project means there must be other factors we need to understand in addition to loss of breeding habitat. The only way we’ll see a turnaround for the population is if we stabilise greenhouse gas emissions. If we don’t, we’ll probably have relatively few emperor penguins left by the turn of this century.”

Journal Reference:

Fretwell, P.T., Bamford, C., Skachkova, A. et al., ‘Regional emperor penguin population declines exceed modelled projections’, Communications Earth & Environment 6, 436 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-025-02345-7

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by British Antarctic Survey (BAS)

Featured image credit: Siggy Nowak | Pixabay