Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press daily roundup (July 31, 2025), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

Cosmic dust opens window on ancient atmosphere

Since the beginning of Earth’s history, tiny particles of rock and metal from space have been hitting our planet. On clear nights, we can even see their traces as shooting stars. Trapped in layers of rock, these micrometeorites can remain preserved for billions of years.

An international research team led by the University of Göttingen and including the Open University, the University of Pisa, and Leibniz University Hannover has developed a method that allows them to reconstruct the atmosphere of the past using fossilized micrometeorites.

The results were published in Communications Earth & Environment.

When metallic micrometeorites from space enter the Earth’s atmosphere, they melt. In addition, iron and nickel oxidise on contact with oxygen in the air. These processes create microscopic spherical structures. They consist of oxide minerals whose oxygen comes from the atmosphere. Countless numbers of them fall to Earth every year, where they are deposited. They offer great potential for drawing conclusions about the past, as their fossilised remains provide a preserved “chemical archive” of the atmosphere from the time of their formation.

The newly developed method allowed researchers at Göttingen University’s Geoscience Centre and the Leibniz University Hannover to determine the composition of oxygen and iron isotopes in tiny fossil micrometeorites from different geological periods with high precision for the first time.

The ratios of different isotopes provide information about the isotopic composition of the early atmosphere. In addition, the data also allow conclusions to be drawn about CO₂ concentrations at that time and about the formation of organic matter around the world, mainly as a result of plant photosynthesis.

The study shows that these tiny spheres are a promising addition to the usual methods used in geological climate research for reconstructing past CO₂ concentrations. “Our analyses show that intact micrometeorites can preserve reliable traces of isotopes over millions of years despite their microscopic size,” explains lead author Dr Fabian Zahnow, formerly Doctoral Researcher at Göttingen University, now at the Ruhr University Bochum.

At the same time, it became clear that geochemical processes in soil and rock change micrometeorites after they have landed on Earth, meaning careful geochemical investigation is essential.

Journal Reference:

Zahnow, F., Suttle, M.D., Lazarov, M. et al., ‘Traces of the oxygen isotope composition of ancient air in fossilized cosmic dust’, Communications Earth & Environment 6, 577 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-025-02541-5

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Göttingen

How cumulative heat exposure affects students

A holistic approach reveals the global spectrum of knowledge on the impact of cumulative heat exposure on young students, according to an article published in the open-access journal PLOS Climate by Konstantina Vasilakopoulou from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, Australia, and Matthaios Santamouris from the University of New South Wales, Australia.

The article aims to shed light on the social and economic inequalities caused within and across countries, the potential adaptive measures to counterbalance the impact of overheating, and forecasts about the cognitive risks associated with future overheating.

Exposure to elevated temperatures, both indoors and outdoors, is strongly associated with adverse health outcomes. The impact of high temperatures and heat stress on human productivity and cognitive performance is well-documented. Most studies indicate that exposure to excessive heat detrimentally affects working memory, information processing, and knowledge retention, thereby impairing overall cognitive performance. The impact of high temperatures on students’ academic performance is profound, influencing their educational, intellectual, and professional achievements.

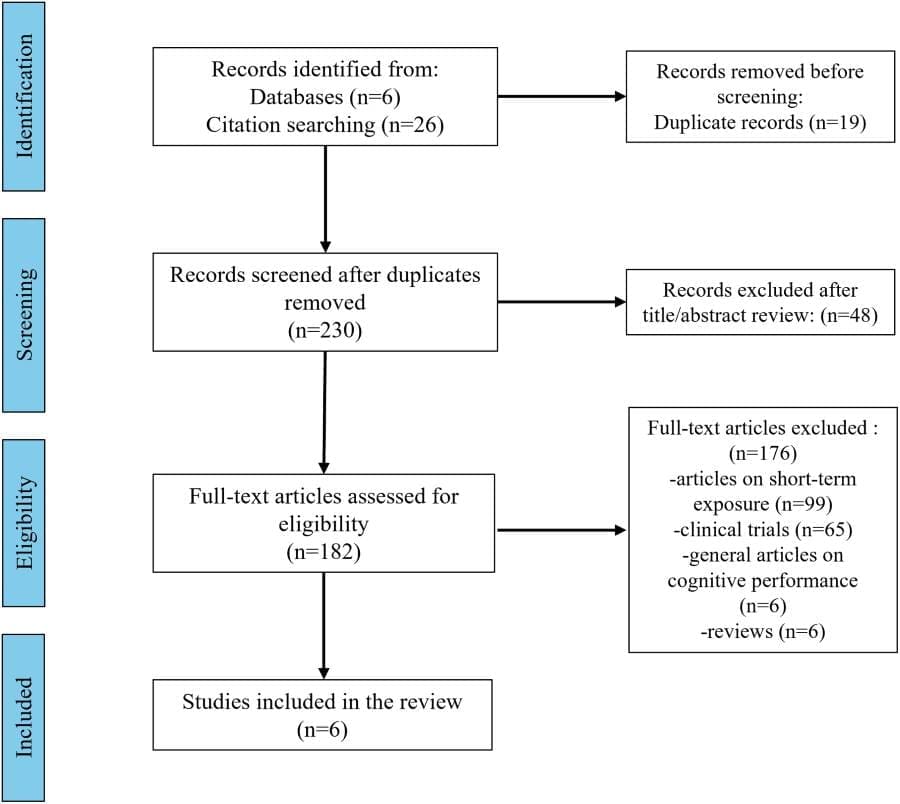

Although there is a plethora of investigations on the momentary and short-term exposure of students to heat and its effects, there is a lack of knowledge and information on the impact of long-term exposure on student cognitive performance. Given the rapid increase in temperature caused by global and regional climate change, understanding the consequences of cumulative exposure to high temperatures on the cognitive ability of students is an urgent priority.

To address this knowledge gap, the authors reviewed seven studies, described in six peer-reviewed articles, that investigated the effects of prolonged heat exposure on students’ cumulative cognitive performance. Collectively, these studies covered an extensive dataset comprising nearly 14.5 million students from 61 countries, linking individual learning outcomes to heat exposure. Overall, the findings suggest that long-term heat exposure negatively impacts students’ cumulative learning, with complex tasks (e.g., mathematics) more affected than simpler ones (e.g., reading).

Six of the seven studies identified a significant negative relationship between extended heat exposure and cognitive performance, while one study found the impact to be minimal. Adaptation via acclimatization and increased air conditioning use showed protective effects. However, lower socioeconomic groups faced disproportionately greater impacts, underlining critical inequalities.

According to the authors, impairments related to cognitive and human capital loss of the young generation may affect the future progress of nations because of the associated dramatic economic, social and cultural implications caused by persistent disruptions to the learning process. The social cost of global overheating will unfortunately affect equity and the quality of life of the vulnerable low-income population. It will accelerate societal discrepancies and will impede economic progress in less developed countries suffering from excessive heat exposure.

There is an urgent need to adopt a new perspective on the cognitive implications of climate change by advancing technologies and implementing robust, targeted policies to safeguard both current and future human capital.

The authors add: “This study critically reviewed the existing literature on the effects of long-term heat exposure – primarily driven by climate change – on students’ cognitive performance. Prolonged exposure to elevated temperatures was consistently linked to reduced learning outcomes, particularly in tasks that require complex cognitive processing, such as mathematics.

“The findings revealed that students in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas are disproportionately affected. Factors contributing to this disparity include higher localized temperatures in low-income communities, limited access to air conditioning at school and at home, and fewer opportunities for academic support services like private tutoring to offset learning losses. Projected climate scenarios indicate that these disparities will only deepen over time, further disadvantaging already vulnerable student populations.

“To mitigate these effects, the literature highlights several adaptive strategies to enhance learning conditions – such as implementing indoor and outdoor cooling systems and improving classroom ventilation.”

They summarize: “This review, conducted over the course of a year, examined a comprehensive range of sources on the subject. The evidence underscores how global warming can produce far-reaching and often overlooked social consequences. Most critically, it reiterates that those bearing the brunt of climate change’s impacts are often those least responsible for it – and least equipped to combat its effects.”

Journal Reference:

Vasilakopoulou K., Santamouris M., ‘Cumulative exposure to urban heat can affect the learning capacity of students and penalize the vulnerable and low-income young population: A systematic review’, PLOS Climate 4, (7): e0000618 (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pclm.0000618

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by PLOS

Large study uncovers specific impacts of flooding on older adult health

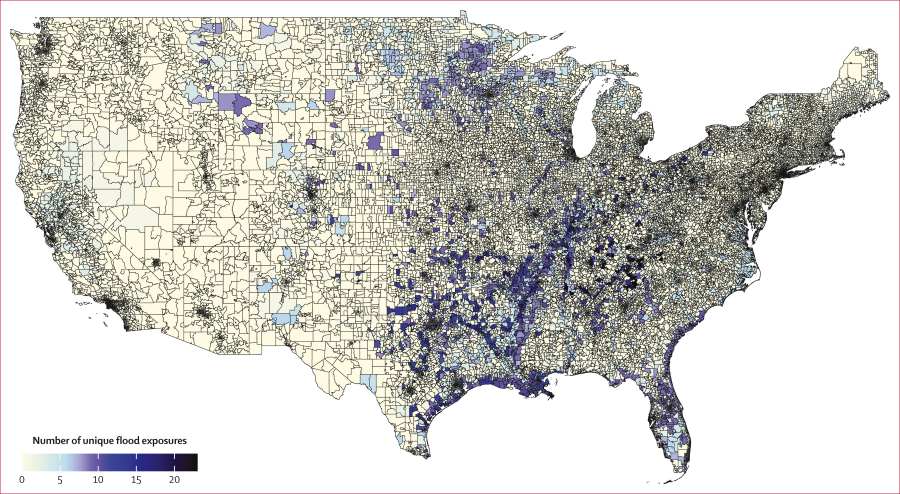

New research examining 17 years of data from Medicare hospitalization claims and major flooding events finds increased rates of skin diseases, nervous system diseases, and injuries or poisonings among adults aged 65 and older following major floods.

Researchers from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Ohio State University, University of Wisconsin–Madison, and Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health published the findings in the journal Lancet Planetary Health.

While past research has been limited to a single flood or a small set of health outcomes, with little information on older individuals, the new study provides robust, generalizable findings that can inform flood preparation in high-income countries.

The researchers matched Medicare hospitalization data from 2000 to 2016, representing adults aged 65 years and older, with satellite-based, high-resolution historical flood maps from the Global Flood Database. They estimated relative percentage changes in hospitalization rates for 13 disease categories within four weeks following flood exposure. These included 72 significant flood events and over 4.5 million hospitalizations.

They observed elevated rates of hospitalization on average during and following flood exposure for skin diseases (3⋅1%), nervous system diseases (2.5%), musculoskeletal system diseases (1.3%), and injuries or poisoning (1.1%). Communities with lower proportions of Black residents experienced worsened effects for nervous system diseases (7.6%), whereas skin diseases (6.1%) and mental health-related impacts (3.0%) were more pronounced for areas with larger percentages of Black residents during flood exposure.

Older adults are particularly vulnerable to flood-related health impacts because of their weakened immune systems, restricted mobility, limited ability to cope with climate hazards due to pre-existing conditions such as dementia, and poor access to medical services for routine appointments.

Skin diseases may be the result of exposure to polluted water sources, crowded shelters, and poor sanitation. Seizures could arise from traumatic brain injuries sustained during floods. For individuals with epilepsy, flood events can induce stress and fatigue that might result in poor seizure control.

Musculoskeletal system hospitalizations may result from underlying conditions and delays in seeking care, as well as injuries from flood clean-up. Distinct patterns of pre-existing conditions, housing quality, and access to emergency resources may explain why some health impacts of flooding are more acute for Black communities. Another possible explanation is differences in access to care and implicit biases in the coding of disease conditions between racial groups.

“The findings of this study provide crucial new insights into the diverse, and previously underappreciated, health consequences of floods in older adults and can guide flood-specific resilience-building efforts to protect public health under climate change,” the researchers write.

“Targeted outreach and robust evacuation planning for vulnerable populations, such as older individuals, along with community-based alert systems, are crucial to minimizing health impacts. Hospital infrastructure should be equipped to function during flood events by moving essential components above flood levels, and mobile medicine units and telemedicine can serve as effective alternatives if access to hospitals is temporarily eliminated. Drones can also deliver essential medical supplies to flood-affected hospitals or help identify safe evacuation routes in real time to guide emergency responders,” they conclude.

The study’s lead author is Sarika Aggarwal, a PhD candidate at Harvard Chan School. Additional authors include Jie K. Hu ( Ohio State University), Jonathan A. Sullivan (University of Wisconsin–Madison), Robbie M. Parks (Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health), and Rachel C. Nethery (Harvard Chan School).

Journal Reference:

Aggarwal, Sarika et al., ‘Severe flooding and cause-specific hospitalisation among older adults in the USA: a retrospective matched cohort analysis’, The Lancet Planetary Health online, 101268 (2025). DOI: 10.1016/S2542-5196(25)00132-9. Also available on ScienceDirect.

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health

Increasing solar power could lead to significant cuts in CO₂ emissions

Key points:

- Researchers estimated that a 15% increase in U.S. solar power generation could reduce CO₂ emissions by 8.54 million metric tons annually, offering major climate benefits.

- The benefits of added solar power varied widely by region. Areas like California, Florida, Texas, Mid-Atlantic, Midwest, and Southwest exhibited major reductions in emissions from solar increases, while other areas, such as Central, New England, and Tennessee, saw minimal impact.

- Solar expansion in one region can reduce emissions in neighboring regions, highlighting the importance of regional collaboration in clean energy planning.

Increasing solar power generation in the U.S. by 15% could lead to an annual reduction of 8.54 million metric tons of carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions, according to a new study led by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The researchers found that the climate benefits of solar power differ markedly across U.S. regions, pinpointing where clean energy investments return the greatest climate dividends.

“This is an exciting study in that it harnesses the power of data science to offer insights to policymakers and stakeholders on how we can achieve CO₂ reduction targets,” said corresponding author Francesca Dominici, director of the Harvard Data Science Initiative and Clarence James Gamble Professor of Biostatistics, Population, and Data Science.

The study is published in Science Advances.

In 2023, 60% of U.S. electricity generation relied on fossil fuels, while just 3.9% came from solar, according to the U.S. Energy Administration. Since fossil fuel-generated electricity is a leading source of both CO₂ and harmful air pollutants such as fine particulate matter, cutting emissions by expanding solar could not only mitigate CO₂ but also help reduce illness, hospitalizations, and premature deaths linked to air pollution exposure.

For this study, the researchers examined five years of hourly electricity generation, demand, and emissions data from the Energy Information Administration, starting July 1, 2018. They focused on 13 regions: California, Carolinas, Central, Florida, Mid-Atlantic, Midwest, New England, New York, Northwest, Southeast, Southwest, Tennessee, and Texas. Using this dataset, they constructed an advanced statistical model to explore how increases in hourly solar energy generation would affect CO₂ emissions within a given region and in its neighboring regions.

The study quantified both immediate and, for the first time, delayed emissions reductions resulting from added solar generation. For example, the researchers found that in California, a 15% increase in solar power at noon was associated with a reduction of 147.18 metric tons of CO₂ in the first hour and 16.08 metric tons eight hours later.

The researchers’ methods provide a more nuanced understanding of system-level impacts from solar expansion than previous studies, pinpointing where the benefits of increased solar energy adoption could best be realized. In some areas, such as California, Florida, Mid-Atlantic, Midwest, Texas, and the Southwest, small increases in solar were estimated to deliver large CO₂ reductions, while in others, such as New England, Central, and Tennessee, impacts were found to be minimal – even with much larger increases in solar generation.

In addition, the study demonstrates the significant spillover effects solar adoption has on neighboring regions, highlighting the value of coordinated clean energy efforts. For example, a 15% increase in solar capacity in California was associated with a reduction of 913 and 1,942 metric tons of CO₂ emissions per day in the Northwest and Southwest, respectively.

“Our study offers policymakers and investors a roadmap for targeting solar investments where emissions reductions are most impactful and where solar energy infrastructure can yield the highest returns,” said lead author Arpita Biswas, assistant professor in the Department of Computer Science at Rutgers University. “From a research perspective, our findings also demonstrate the power of harnessing large-scale, high-resolution energy data to generate actionable insights.”

Other Harvard Chan authors included Danielle Braun and Daniel Mork.

Journal Reference:

Arpita Biswas, Minghao Qiu, Danielle Braun, Francesca Dominici and Daniel Mork, ‘Quantifying effects of solar power adoption on CO₂ emissions reduction’, Science Advances 11, 31: eadq5660 (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adq5660

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

Weathering change: Fewer cold fatalities, more heat emergencies in California

As temperatures rise, California is experiencing fewer deaths from cold temperatures, which outweigh increased deaths from extreme heat. However, hotter temperatures sharply increase emergency department visits – a previously overlooked consequence of climate change that could place a greater burden on the healthcare system.

Using data covering all deaths, emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations and daily temperatures in California from 2006 to 2017, researchers from the University of California San Diego and Stanford University reported that hot and cold days influence illness and deaths differently in California.

The findings were published in the journal Science Advances.

“Heat can harm health even when it doesn’t kill,” said Carlos F. Gould, Ph.D., assistant professor at the Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health and Human Longevity Science at UC San Diego and first author of the study. “Warmer temperatures were consistently associated with more trips to the emergency department, so studies and planning that only consider mortality miss a big slice of the burden.”

Varied health impact by age

The study found that emergency room visits, which reflect a wider range of health impacts across age groups, rise sharply with hotter days. Conditions like injuries, mental health issues, and poisonings show clear increases with heat but are not major causes of death, so they are often missed in studies that focus only on mortality.

“Age plays a critical role in shaping health risks from temperatures,” said Gould. “Older adults are particularly vulnerable to cold temperatures, whereas younger adults and children are more affected by heat.”

While California may see fewer cold‑related deaths as the state experiences fewer extreme cold days, that benefit will be partly offset by more trips to the emergency room as a result of more extreme heat. Researchers suggest that health policy needs to account for differences to address temperature-related impacts in the full population – hospitals, insurers and public health agencies should prepare for heavier heat demand and tailor warnings and resources to different age groups.

“Understanding who is affected, how, and at what temperatures is critical for planning appropriate responses to protect health,” said study co-author Marshall Burke, Ph.D., associate professor of environmental social sciences at the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability. “This is true with or without climate change, but a warming climate makes it more important and alters who is exposed to what.”

Economic and social burden of climate change

Healthcare spending in the United States on chronic disease alone is estimated to exceed $3 trillion annually, which accounts for 17.6% of US gross domestic product, according to the National Health Expenditure Accounts.

Using projections based on moderate climate change scenarios through 2050, researchers estimate California will see around 53,500 fewer deaths overall due to less cold weather – saving approximately $30 billion annually. However, this is partially offset by an estimated additional 1.5 million heat-driven emergency department visits, costing an extra $52 million annually in healthcare spending.

“We often think about only the most extreme health impacts of heatwaves: deaths. This work is showing that many things that we may not think about being sensitive to extreme heat are, like poisonings, endocrine disorders, injuries and digestive issues,” said Alexandra K. Heaney, Ph.D., assistant professor at the Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health and co-author of the paper. “We need to focus on the full spectrum of health impacts when we think about heatwaves, now and in the future.”

Co-authors include: Carlos F. Gould and Alexandra K. Heaney at UC San Diego; Sam Heft-Neal, Eran Bendavid, Christopher W. Callahan, Mathew V. Kiang, and Marshall Burke at Stanford University; and Josh Graff Zivin, UC San Diego and the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Journal Reference:

Carlos F. Gould et al., ‘Temperature extremes impact mortality and morbidity differently’, Science Advances 11, 31: eadr3070 (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adr3070

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Tyler DeLong | University of California – San Diego (UC San Diego)

Carbon ‘offsets’ aren’t working. Here’s a way to improve nature-based climate solutions

A lot of the climate-altering carbon pollution we humans release into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels gets drawn into Earth’s oceans and landscapes through natural processes, mostly through photosynthesis as plants turn atmospheric carbon dioxide into biomass.

Efforts to slow the climate crisis have long sought to harness nature, often through carbon “offsets,” aimed at bolstering forests, wetlands, and agriculture, but have generally had only marginal success so far.

A new approach: contributions vs. credits

New research led by the University of Utah’s Wilkes Center for Climate Science & Policy offers a “roadmap” for accelerating climate solutions. Published in the journal Nature, the paper analyses various strategies for improving such nature-based climate solutions, or NbCS, specifically exploring the role of the world’s forests in pulling carbon out of the atmosphere and storing it in long-lived trees and even in the ground.

“Nature-based climate solutions are human actions that leverage natural processes to either take carbon out of the atmosphere or stop the emissions of carbon to the atmosphere,” said lead author and forest ecologist William Anderegg, a professor of biology and past Wilkes Center director. “Those are the two main broad categories. There are the avoided emissions, and that’s activities like stopping deforestation. Then there’s the greenhouse gas-removal pathways. That’s things like reforestation where you plant trees, and as those trees grow, they suck up CO₂ out of the atmosphere.”

The U-led study, which includes leading scientists from nine other universities as part of a Wilkes Center Working Group effort, identifies four components where nature-based climate actions have not lived up to their billing and proposes reforms to improve their performance and scalability.

Forests are the focus because of trees’ ability to store vast amounts of carbon that would otherwise be in the atmosphere exacerbating the climate crises. Conversely, deforestation, especially in the Amazon rainforest, is releasing carbon at an alarming rate.

About half the emissions associated with human activity are absorbed into plants, through photosynthesis, and oceans, with the rest building up in the atmosphere where these gases trap heat. Terrestrial ecosystems pull 31% of anthropogenic emissions out of the atmosphere, according to the study. While forests are seen as Earth’s most vital carbon sponge, current rates of deforestation release 1.9 gigatons of carbon a year, on par with Russia’s annual emissions. Thus, “actions to halt and reverse deforestation are a critical part of climate stabilization pathways,” the authors write.

The trouble with carbon offsets

Various programs are in place for companies to mitigate their emissions through purchasing “carbon offsets,” which fund projects aimed at preserving or restoring forests. But as currently configured, these programs are not delivering much in the way of climate benefits, according to Libby Blanchard, a postdoctoral researcher in Anderegg’s Utah lab.

“There are widespread problems with accounting for their climate impact,” said Blanchard, the paper’s second author who has extensively studied the impacts of offset programs. “For example, despite the potential for albedo to reduce or even negate the climate mitigation benefits of some forest carbon projects, calculating for the effect of albedo is not considered in any carbon-crediting protocols to date.”

To succeed, according to the study, a nature-based climate solution should

- lead to net global cooling;

- result in additional climate benefits;

- avoid carbon “leakage”;

- store carbon long enough to make a difference.

Finally, the study proposes structural reforms aimed at encouraging corporations to financially contribute to climate mitigation, as opposed to claim credit for something that may ultimately provide little climate benefit. A contribution approach would be more scientifically accurate and legally defensible than the current system, potentially resulting in higher quality projects, the authors argue.

The four critical factors explained

The first piece of the roadmap calls for accounting the various feedbacks to ensure that the NbCS results in an actual cooling effect on the climate. Planting trees can change a landscape’s albedo, that is its capacity to reflect the sun’s energy back into space.

“If you go in an ecosystem that is mostly snow covered and you plant really dark conifer trees, that can actually outweigh the carbon storage benefit and heat up the planet,” Anderegg said.

Next, the project must result in actions that that would not have otherwise occurred.

“You have to change behavior or change some sort of outcome,” Anderegg said. “You can’t just take credit for what was going to happen anyway. One great example here is if you pay money to keep a forest from deforestation, but it was never going to be cut down to begin with, then you haven’t done anything for the climate.”

The third problem is known as “leakage,” which occurs when a climate action simply pushes a land-disturbing activity from one place to another.

And the fourth component address climate actions’ durability, or how long they will keep carbon out of the atmosphere. This is particularly important given the longevity of carbon dioxide molecules. When fossil fuels are burned, carbon that was permanently locked in geological formations is released into the biosphere where it will cycle in and out of living things and landscapes for thousands of years.

A climate solution should always aim to keep carbon locked up for as long as possible, preferably at least a century. But drought, storms, insects, wildfire and other climate-related hazards can quickly negate any gains by killing trees.

“You have to know how big the risks are, and you have to account for those risks in the policies and programs,” Anderegg said. “Otherwise, basically you’re going to lose a lot of that carbon storage as climate change accelerates the risks.”

The methods now in place, known as “buffer pools,” to account for these risks are not robust or rigorous currently, according to research by Anderegg’s lab, which expects to release a study soon highlighting potential fixes.

Journal Reference:

Anderegg, W.R.L., Blanchard, L., Anderson, C. et al., ‘Towards more effective nature-based climate solutions in global forests’, Nature 643, 1214–1222 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09116-6

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Brian Maffly | University of Utah

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay