Summary:

About 56 million years ago, during a time of rapid global warming known as the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), a jackal-sized predator called Dissacus praenuntius adapted in a surprising way: it shifted from a flesh-heavy diet to eating more bones.

This discovery, detailed in a study published in Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, sheds light on how climate change can drive dramatic changes in animal diets and offers lessons for modern species facing environmental upheaval. Led by Andrew Schwartz at Rutgers University, the research team used dental microwear texture analysis to examine microscopic scratches and pits on fossil teeth, revealing the animal’s dietary habits before, during, and after the PETM. The analysis showed that as ecosystems changed and prey became scarce, Dissacus adapted by consuming harder, more brittle foods, likely bones, mirroring survival strategies seen in modern carnivores facing habitat loss.

This dietary flexibility, paired with a slight reduction in body size, suggests that ecological disruption – not temperature alone – played a key role in driving evolutionary responses. The study highlights that animals with more adaptable diets may be better equipped to survive the challenges of today’s rapidly warming world.

An ancient predator’s shift in diet offers clues on surviving climate change

About 56 million years ago, when Earth experienced a dramatic rise in global temperatures, one meat-eating mammal responded in a surprising way: It started eating more bones.

That’s the conclusion reached by a Rutgers-led team of researchers, whose recent study of fossil teeth from the extinct predator Dissacus praenuntius reveals how animals adapted to a period of extreme climate change known as the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM). The findings could help scientists predict how today’s wildlife might respond to modern global warming.

“What happened during the PETM very much mirrors what’s happening today and what will happen in the future,” said Andrew Schwartz, a doctoral student in the Department of Anthropology at the School of Arts and Sciences, who led the research. “We’re seeing the same patterns. Carbon dioxide levels are rising, temperatures are higher and ecosystems are being disrupted.”

Associate Professor Robert Scott of the Department of Anthropology is a co-author of the study.

Schwartz, Scott and another colleague used a technique called dental microwear texture analysis to study the tiny pits and scratches left on fossilized teeth. These marks reveal what kinds of food the animal was chewing in the weeks before it died.

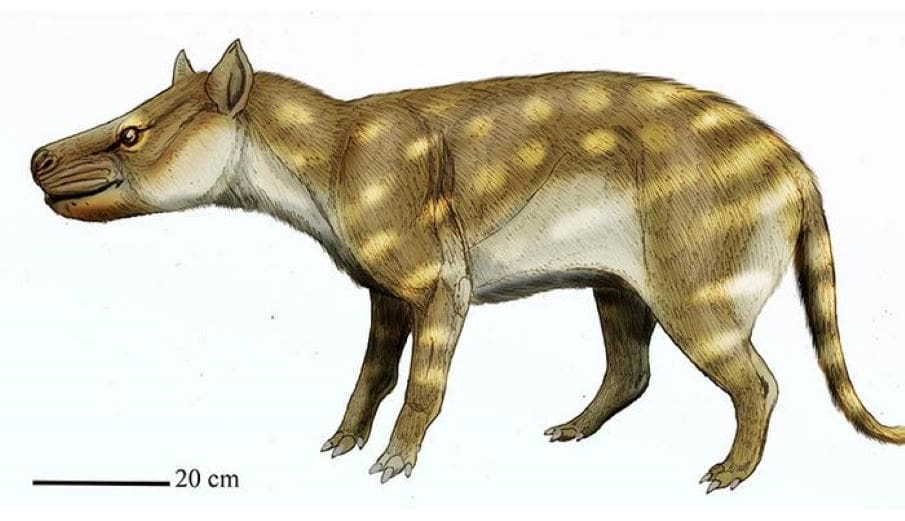

The ancient omnivore was about the size of a jackal or a coyote and likely consumed a mix of meat and other food sources like fruits and insects. “They looked superficially like wolves with oversized heads,” Schwartz said, describing them as “super weird mammals.” “Their teeth were kind of like hyenas. But they had little tiny hooves on each of their toes.”

Before this period of rising temperatures, Dissacus had a diet similar to modern cheetahs, eating mostly tough flesh. But during and after this ancient period, its teeth showed signs of crunching harder materials, such as bones.

“We found that their dental microwear looked more like that of lions and hyenas,” Schwartz said. “That suggests they were eating more brittle food, which were probably bones, because their usual prey was smaller or less available.”

This dietary shift happened alongside a modest reduction in body size, likely because of food scarcity. While earlier hypotheses blamed shrinking animals on hotter temperatures alone, this latest research suggests that limited food played a bigger role, Schwartz said.

This period of rapid global warming lasted about 200,000 years, but the changes it triggered were fast and dramatic. Schwartz said studies of the past like his can offer practical lessons for today and what comes next.

“One of the best ways to know what’s going to happen in the future is to look back at the past,” he said. “How did animals change? How did ecosystems respond?”

The findings also highlight the importance of dietary flexibility, he said. Animals that can eat a variety of foods are more likely to survive environmental stress.

“In the short term, it’s great to be the best at what you do,” Schwartz said. “But in the long term, it’s risky. Generalists, meaning animals that are good at a lot of things, are more likely to survive when the environment changes.”

Such an insight may be helpful for modern conservation biologists, allowing them to identify which species today may be most vulnerable, he said. Animals with narrow diets, such as pandas, may struggle as their habitats shrink. But adaptable species, including jackals or raccoons, might fare better.

“We already see this happening,” Schwartz said. “In my earlier research, jackals in Africa started eating more bones and insects over time, probably because of habitat loss and climate stress.”

The study also showed that rapid climate warming as seen during the ancient past can lead to major changes in ecosystems, including shifts in available prey and changes in predator behavior. This may suggest that modern climate change could similarly disrupt food webs and force animals to adapt, or risk extinction, he said.

Even though Dissacus was a successful and adaptable animal that lived for about 15 million years, it eventually went extinct. Scientists think this happened because of changes in the environment and competition from other animals, Schwartz said.

Schwartz conducted his research using a combination of fieldwork and lab analysis, focusing on fossil specimens from the Bighorn Basin in Wyoming, a site with a rich and continuous fossil record spanning millions of years. Schwartz chose the location because it preserves a detailed sequence of environmental and ecological changes during the ancient period of climate warming.

Schwartz has been interested in paleontology, specifically dinosaurs, since he was a boy, journeying with his father, an amateur fossil hunter, on treks through New Jersey’s rivers and streams. Now, as a late-stage doctoral student, he hopes to use ancient fossils to answer urgent questions about the future.

He also wants to inspire the next generation of researchers.

“I love sharing this work,” he said. “If I see a kid in a museum looking at a dinosaur, I say, ‘Hey, I’m a paleontologist. You can do this, too.’”

In addition to Schwartz and Scott, Larisa DeSantis of Vanderbilt University is an author of the study.

Journal Reference:

Andrew Schwartz, Larisa R.G. DeSantis, Rob S. Scott, ‘Dietary change across the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum in the mesonychid Dissacus praenuntius’, Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 675, 113089 (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2025.113089

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Kitta MacPherson | Rutgers University

Featured image: Ancient soils preserved in the rock, known as paleosols, in the Willwood Formation, Bighorn Basin, Wyoming, are rich fossil sites. Credit: Andrew Schwartz | Rutgers University