Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press daily roundup (September 24, 2025), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

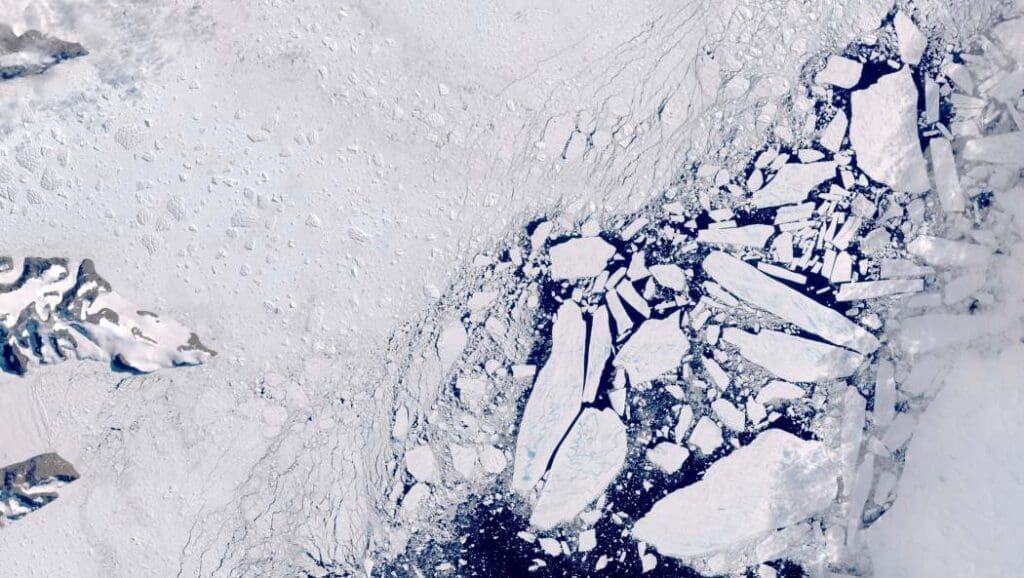

Scientists say next few years vital to securing the future of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet

Collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could be triggered with very little ocean warming above present-day, leading to a devastating four metres of global sea level rise to play out over hundreds of years according to a study now published in Communications Earth & Environment, co-authored by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK). However, the authors emphasise that immediate actions to reduce emissions could still avoid a catastrophic outcome.

Scientists at PIK, the Norwegian research centre NORCE and Northumbria University in the United Kingdom conducted model simulations going back 800,000 years to give an extended view of how the vast Antarctic Ice Sheet has responded in the past to the Earth’s climate as it moved between cold “glacial” and warmer “interglacial” periods.

“In the past 800,000 years, the Antarctic Ice Sheet has had two stable states that it has repeatedly tipped between. One, with the West Antarctic Ice Sheet in place, is the state we are currently in. The other state is where the West Antarctic Ice Sheet has collapsed,” lead author David Chandler from NORCE commented.

The major driver of change between the two states is rising ocean temperatures around Antarctica, because the heat melting the ice in Antarctica is supplied mostly by the ocean, rather than the atmosphere. Once the ice sheet has tipped to the collapsed state, reversal back to the stable present-day state would need several thousands of years of temperatures at or below pre-industrial conditions.

“Once tipping has been triggered it is self-sustaining and seems very unlikely to be stopped before contributing to about four meters of sea-level rise. And this would be practically irreversible,” Chandler said.

“It takes tens of thousands of years for an ice sheet to grow, but just decades to destabilise it by burning fossil fuels. Now we only have a narrow window to act,” said co-author Julius Garbe from PIK.

Journal Reference:

Chandler, D.M., Langebroek, P.M., Reese, R. et al., ‘Antarctic Ice Sheet tipping in the last 800,000 years warns of future ice loss’, Communications Earth & Environment 6, 420 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-025-02366-2

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by The Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK)

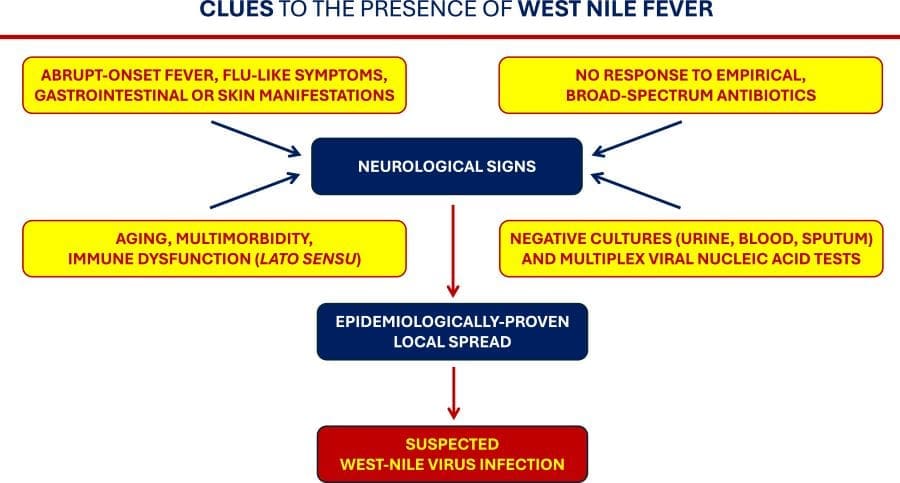

“We need to prepare for a growing number of West Nile virus infections,” experts warn

Growing numbers of West Nile virus infection cases, fueled by climate change, are sparking fears among citizens and healthcare providers in Europe. A Clinical Insight in the European Journal of Internal Medicine, published by Elsevier, aims to raise awareness and equip medical professionals with the knowledge needed to recognize and manage this emerging disease to avoid further spread and serious health consequences, especially for vulnerable individuals.

“Climate change is affecting our health by allowing disease-carrying insects to spread into new areas. We are now seeing a growing number of illnesses like West Nile virus infection in places they were not found before, including in Europe. Since the number of West Nile virus cases is on the rise, it is now more important than ever to increase our knowledge to recognize, diagnose, and treat this emerging disease,“ says lead author Emanuele Durante-Mangoni, MD, PhD, University of Campania ‘L. Vanvitelli,’ and AORN Ospedali dei Colli, Naples, Italy.

The West Nile virus is a mosquito-borne virus that can attack the nervous system and brain. It was first identified in 1937 west of the Nile River in what is now Uganda. It is a highly variable virus for which no human vaccine is currently available. However, identification of the disease can facilitate identifying areas of spread where dedicated interventions, largely mosquito eradication, can be performed in an attempt to avoid further spread and related morbidity.

Dr. Durante-Mangoni explains: “The insect gets infected after biting birds that carry the virus. Seasonality is also linked to bird migration patterns, another natural phenomenon affected by climate change. After West Nile virus infection, most humans show no symptoms (80%) or develop mild symptoms of a viral illness, typically characterized by the abrupt onset of fever. It is also associated with headache, malaise, anorexia, myalgia, eye pain, diarrhea, and vomiting. In some at-risk individuals, such as the elderly, those who are frail, or have other health issues, the disease can progress to a more serious form, often involving the brain, and can possibly have severe or even fatal consequences.”

The authors’ goal is to help prepare the scientific community to deal with the expected increase in the incidence of West Nile virus cases by outlining the virology, clinical presentation, diagnostic approach, and the current suggested management of this emerging disease. They advise that efforts should concentrate on:

- Working towards developing a vaccine for human use that can protect those at higher risk of complications and/or progression;

- Trying to identify an antiviral agent that can block the virus at an early stage, before neurological involvement occurs.

“Clinicians need to become skilled enough to identify the illness and make a rapid and accurate diagnosis and also be aware of endemic/epidemic areas of West Nile virus diffusion, to speed up the diagnostic path in frail and immunocompromised patients who remain at risk for an ominous outcome,” emphasizes Dr. Durante-Mangoni. “The ultimate strategy would be vaccination of subjects at risk. Despite efforts, as yet no vaccine has reached an advanced stage of clinical development, but there is hope for the future.”

Journal Reference:

Raffaella Gallo, Rosanna C. De Rosa, Emanuele Durante-Mangoni, ‘From vectors to victims: understanding the threat of West Nile virus infection’, European Journal of Internal Medicine 139, 106449 (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.ejim.2025.106449. Also available on ScienceDirect.

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Elsevier

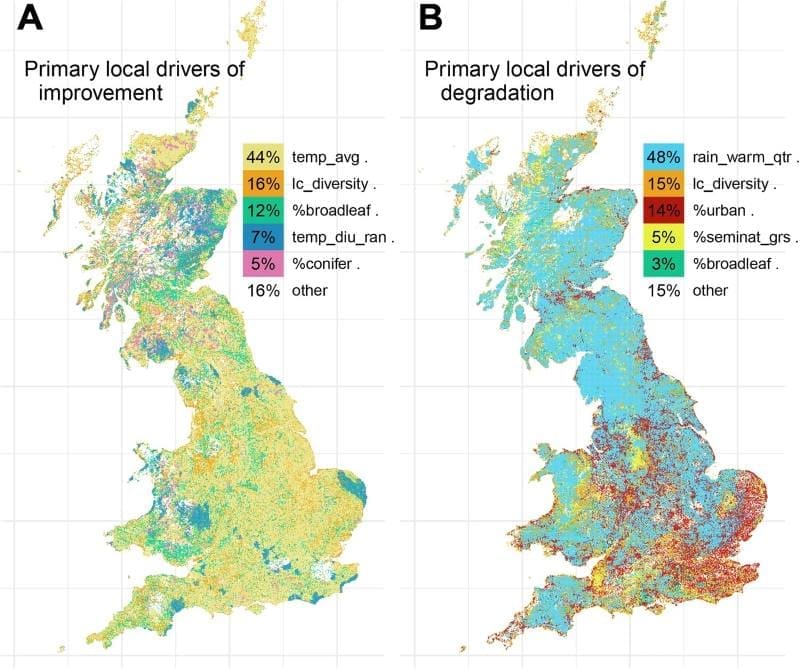

Insects in Britain not in freefall, but facing local upheavals, study finds

Fears of a nationwide collapse in Britain’s insect populations may be overstated, according to a major new study published in Nature Communications. Instead, researchers have found a more complex picture: while some species are holding steady or even expanding, many communities are being reshaped at a local level by climate change and urban development.

The study team, including staff at the Rothamsted national insect survey, analysed more than three decades of records covering 1,252 species of butterflies, moths, dragonflies, grasshoppers, beetles, bees, wasps and hoverflies. Using advanced machine-learning models, they tracked changes in where insects live across Great Britain and pinpointed the main environmental forces driving those shifts.

Contrary to widespread fears of an overall collapse, the team detected no nationwide decline in insect occupancy since 1990. But beneath that headline figure, the data revealed profound local changes in the make-up of insect communities.

Urban sprawl and the simplification of farmland emerged as key drivers of decline in certain species, while rising temperatures are altering life cycles. Insects with narrow habitat requirements are particularly vulnerable to the loss of diverse landscapes, while species capable of breeding multiple times a year are better able to adapt to a warming climate.

“The findings suggest that while Britain may not be witnessing an outright crash in insect numbers, it is undergoing a subtler but no less significant ecological reshuffling,” said Rothamsted population modeller Dr Yoann Bourhis who led the study. This could have knock-on effects for pollination, pest control and wider biodiversity.”

Journal Reference:

Bourhis, Y., Milne, A.E., Shortall, C.R. et al., ‘Trait mediation explains decadal distributional shifts for a wide range of insect taxa’, Nature Communications 16, 8131 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-63093-y

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Rothamsted Research

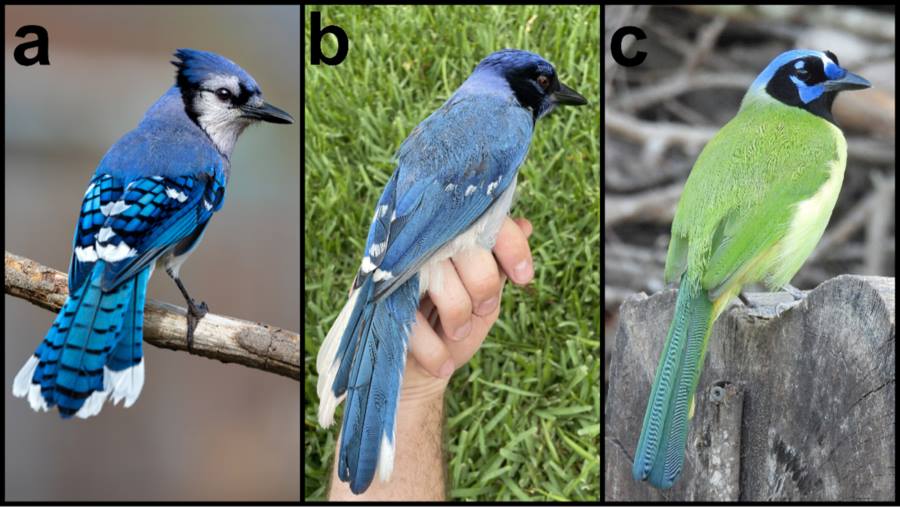

So what should we call this – a grue jay?

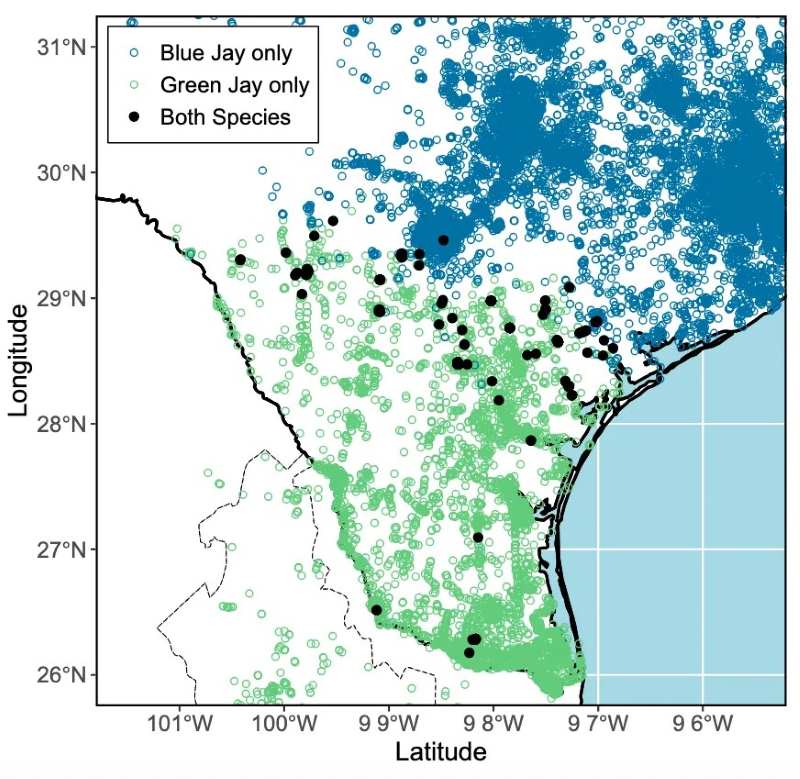

Biologists at The University of Texas at Austin, who have reported discovering a bird that’s the natural result of a green jay and a blue jay’s mating, say it may be among the first examples of a hybrid animal that exists because of recent changing patterns in the climate.

The two different parent species are separated by 7 million years of evolution, and their ranges didn’t overlap as recently as a few decades ago.

“We think it’s the first observed vertebrate that’s hybridized as a result of two species both expanding their ranges due, at least in part, to climate change,” said Brian Stokes, a graduate student in ecology, evolution and behavior at UT and first author of the study.

Stokes noted that past vertebrate hybrids have resulted from human activity, like the introduction of invasive species, or the recent expansion of one species’ range into another’s – think polar bears and grizzlies – but this case appears to have occurred when shifts in weather patterns spurred the expansion of both parent species.

In the 1950s, the ranges of green jays, a tropical bird found across Central America, extended just barely up from Mexico into south Texas and the range of blue jays, a temperate bird living all across the Eastern U.S., only extended about as far west as Houston. They almost never came into contact with each other. But since then, as green jays have pushed north and blue jays have pushed west, their ranges have converged around San Antonio.

As a Ph.D. candidate studying green jays in Texas, Stokes was in the habit of monitoring several social media sites where birders share photos of their sightings. It was one of several ways he located birds to trap, take blood samples for genetic analysis and release unharmed back to the wild. One day, he saw a grainy photo of an odd-looking blue bird with a black mask and white chest posted by a woman in a suburb northeast of San Antonio. It was vaguely like a blue jay, but clearly different. The backyard birder invited Stokes to her house to see it firsthand.

“The first day, we tried to catch it, but it was really uncooperative,” Stokes said. “But the second day, we got lucky.”

The bird got tangled in a mist net, basically a long rectangular mesh of black nylon threads stretched between two poles that is easy for a flying bird to overlook as it’s soaring through the air, focused on some destination beyond. Stokes caught and released dozens of other birds, before his quarry finally blundered into his net on the second day.

Stokes took a quick blood sample of this strange bird, banded its leg to help relocate it in the future, and then let it go. Interestingly, the bird disappeared for a few years and then returned to the woman’s yard in June 2025. It’s not clear what was so special about her yard.

“I don’t know what it was, but it was kind of like random happenstance,” he said. “If it had gone two houses down, probably it would have never been reported anywhere.”

According to an analysis by Stokes and his faculty advisor, integrative biology professor Tim Keitt, published in the journal Ecology and Evolution, the bird is a male hybrid offspring of a green jay mother and a blue jay father. That makes it like another hybrid that researchers in the 1970s brought into being by crossing a green jay and a blue jay in captivity. That taxidermically preserved bird looks much like the one Stokes and Keitt describe and is in the collections of the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History.

“Hybridization is probably way more common in the natural world than researchers know about because there’s just so much inability to report these things happening,” Stokes said. “And it’s probably possible in a lot of species that we just don’t see because they’re physically separated from one another and so they don’t get the chance to try to mate.”

The scientists’ work was supported by a ConTex Collaborative Research Grant through UT System, the Texas EcoLab Program and Planet Texas 2050, a University of Texas at Austin grand challenge initiative.

The researchers did not opt to name the hybrid bird, but other naturally occurring hybrids have received nicknames like “grolar bear” for the polar bear-grizzly hybrid, “coywolf” for a creature that’s part coyote and part wolf and “narluga” for an animal with both narwhal and beluga whale parents.

Journal Reference:

Stokes, B. R., and T. H. Keitt., ‘An Intergeneric Hybrid Between Historically Isolated Temperate and Tropical Jays Following Recent Range Expansion’, Ecology and Evolution 15, 9: e72148 (2025). DOI: 10.1002/ece3.72148

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Marc Airhart | University of Texas at Austin

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay