Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press daily roundup (November 5, 2025), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

California surface water costs triple during drought

California often swings between climate extremes – from powerful storms to punishing droughts. As climate change drives more intense and frequent dry and wet cycles, pressure on California’s water supplies grows.

A new University of California, Davis, economic study finds that drought in California pushes the price of water from rivers, lakes and reservoirs up by $487 per acre-foot, more than triple the cost during an average wet year. The research appears in Nature Sustainability.

Groundwater prices stable

“The extreme volatility in prices surprised me,” said lead author Madeline Turland, a former graduate student in the UC Davis Agricultural and Resource Economics Department and now an assistant professor of resource economics at the University of Alberta. “During dry years we have really high surface water prices and during wet years we have really low water prices, but we found that groundwater seems to have stable prices over time, despite precipitation swings.”

California groundwater basins can store eight to 12 times more water than all the state’s reservoirs combined yet are not widely used to store surplus surface water. The study suggests that managing groundwater and surface water together could keep water prices steady and support the state’s economy.

“This study shows why coordinating both sources matters – it can lower costs now and help communities and farmers better weather future climate swings,” Turland said.

Surface water prices volatile

Researchers looked at water transaction data from 2010 to 2022, which spanned both drought and deluge in California. During that time, surface water prices varied with precipitation, while groundwater prices remained stable.

The study also found that more water storage could help protect California from climate-driven price swings. But researchers said building new reservoirs, raising dams and removing sediment from existing reservoirs also come with high fiscal, environmental and social costs and may bring only marginal or temporary increases in storage capacity.

Legal and policy challenges

Turland noted that California’s system of water rights makes joint management challenging. Surface water is allocated based on seniority of water rights. Except for adjudicated groundwater basins, where courts assign rights in response to legal disputes, there are no formal rights to groundwater.

That could change as groundwater agencies comply with California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, which requires that groundwater basins reach sustainability targets by 2040. Courts could play a major role in many of those plans, Turland said.

***

Other authors of the study include Colin A. Carter, Bulat Gafarov, Jens Hilscher and Katrina Jessoe with UC Davis. The study was supported by the United States Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture and the Giannini Foundation of Agricultural Economics.

Journal Reference:

Turland, M., Carter, C.A., Gafarov, B. et al., ‘Price sensitivity to precipitation and water storage in California’, Nature Sustainability (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41893-025-01659-w

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Amy Quinton | University of California – Davis (UC Davis)

Fishes, young and old, are shrinking in Michigan’s inland lakes

A new study led by the University of Michigan shows that changes in climate are also changing the size of fishes in Michigan’s inland lakes. Using data that covered 75 years and nearly 1,500 lakes, researchers have shown that, for several species, old and young fish in 2020 were significantly smaller than their typical size in 1945.

“Climate change is altering the size of different organisms around the world, including fishes in lakes here in Michigan,” said Peter Flood, a postdoctoral research fellow at the U-M School for Environment and Sustainability, or SEAS. “And most of those changes we’re seeing in Michigan fishes are declines in size through time.”

Flood is also the lead author of a new study published in the journal Global Change Biology and was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation and Michigan Institute for Data and AI in Society, or MIDAS. The report is the latest to make use of data amassed by a community science project that digitized decades worth of observation cards that characterize fishes over time in 1,497 inland lakes in Michigan.

This allowed Flood and his colleagues not only to track the sizes of 13 different species, but also of different age groups within those species. The team found that, out of 125 species-age class combinations, 58 had changed size. Of those 58 that changed, 46 were smaller.

“The largest decreases in length over time were found in the youngest and oldest fishes,” Flood said. “Both of those groups have outsized roles in maintaining healthy fish populations and ecosystem functions and services.”

The predators of these fishes are largely gape limited, Flood said, which means they can only eat what fits in their mouths. When younger fishes are smaller, then, they’re easier prey, which can limit the population of not only the current generation, but future ones as well. And while older fishes don’t have the same impact on population dynamics, they still have important roles in their communities, he said.

“We don’t often think about culture with fishes, but they’re more social than we realize. They are learning from each other to some extent,” Flood said. “And these old individuals, they have this outsized influence on keeping the ecosystems healthy, for a variety of reasons.”

Beyond the ecological implications, changes in the size of individual fishes and their populations are important considerations for those who fish and manage Michigan’s fisheries. The DNR sets limits on the size and number of fish that anglers can keep to maintain healthy populations. With climate change putting key characteristics in flux, understanding the nature of the changes could help managers stay ahead of the curve.

“Our study is showing that there are differential responses of certain age ranges, so this is a tool in the toolbox managers can use to try to mitigate some of these climate change effects,” Flood said.

For those who might be wondering how you determine the age of a fish, the answer is in its scales. As the scales grow, they form ring-like patterns, almost like a tree, that can be similarly analyzed to deduce an age.

The data behind the study were collected and maintained by a collaboration between the university and what would become the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, or DNR. Today that collaboration is known as the Institute for Fisheries Research. But an online platform called Zooniverse invited contributors from around the world to help digitize these records so researchers could more easily reveal trends and insights hidden in the ocean of data.

Unearthing such findings in historical and contemporary data is one of the broader goals of work led by the research team of Karen Alofs, a senior author of the study and an associate professor at SEAS. For example, Alofs and her team have also shown that largemouth bass, which are adapted for warmer temperatures, have become more abundant as Michigan’s lakes have warmed. They’ve also found that mass mortality events for fish in these lakes, which typically happened as ice thawed in the spring, are happening later in the year as lakes experience less ice.

“Each of these changes, whether size, abundance or mortality, has important implications for these ecosystems,” Alofs said.

The DNR is still collecting data on the fish, which means researchers like Alofs, Flood and their colleagues can keep an eye on these trends moving forward. But the data also has more dimensions to probe, enabling researchers to ask more questions that could help address new questions, such as how climate change is driving the size changes for different species.

“There’s still so much more that can still be done with this data set,” Flood said. “There aren’t many out there in the world like this one because of the crowdsourced part of it.”

The team is also starting to incorporate fish specimens from the U-M Museum of Zoology into their study. The museum’s Division of Fishes has about 3.5 million specimens from around the world, letting the scientists look even further back in time and examine more species. That includes more fish native to Michigan that haven’t been studied as much because they aren’t fisheries targets, Alofs said.

Katelyn King, a fisheries research biologist, and Kevin Wehrly, research station manager, with the DNR also contributed to the study. U-M team members also included undergraduate researcher Katilin Schiller and Andrew Runyon, who worked on the project as an aquatic biology lab manager.

Journal Reference:

Flood, P. J., K. E. Schiller, K. B. S. King, A. D. Runyon, K. E. Wehrly, and K. M. Alofs, ‘Long-Term and Regional-Scale Data Reveal Divergent Trends of Different Climate Variables on Fish Body Size Over 75 Years’, Global Change Biology 31, 11: e70584 (2025). DOI: 10.1111/gcb.70584

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Michigan

Tie climate action to protecting a way of life to increase motivation, study says

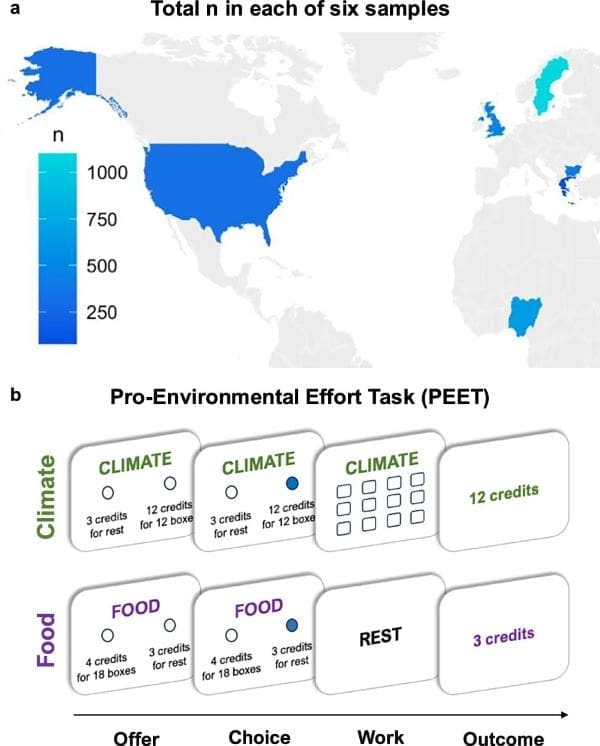

People need to feel that climate change is affecting them now or that taking action is a patriotic act for their country to overcome apathy towards environmental efforts, a new global study has found.

In a paper published in Communications Psychology, a global team of researchers led by the University of Birmingham have found that motivational interventions to successfully make climate action more important to people include showing how climate change is happening now and affecting them or others like them.

The research team worked with participants from six countries around the world: the UK, USA, Bulgaria, Greece, Sweden and Nigeria. People who didn’t experience one of the interventions were less motivated to exert physical effort to help climate causes than for when effort helped tackle starvation. However, some interventions presented before measuring motivation removed this bias, increasing relative motivation to benefit the environment.

The most effective idea presented to participants was to address psychological distance – the feeling that climate change doesn’t personally affect them or those around them. This intervention presented information about how climate change affected them locally for instance. The second uses the psychology of system justification – the idea that the current system of living and doing things is the right one. This intervention showed how climate change threatened participants’ way of life, for example floods in the UK destroying Britons’ homes, and presented climate action as a patriotic act to prevent this.

Dr Jo Cutler from the University of Birmingham and a lead author of the paper said: “From cycling rather than driving to organising waste for recycling, many of the actions we can take to tackle climate change require us to exert physical effort. This global study found that participants around the world can be responsive to interventions that encourage climate action. We found that the most effective interventions were those that show climate change is already affecting people and their way of life may be changed or lost due to climate change. Interventions using this information led to participants being as willing to put in effort as for a more universally recognised cause like ending world hunger.

“Lots of previous research on climate change simply asks people about their attitudes or behaviours they plan to do but there is no incentive for them to be honest. In our experiment, if people want to help, they have to work hard for it. We hope this approach will become more common in future work.”

Participants taking part in the study were asked a series of screening questions to assess their beliefs and attitudes about climate change, before taking part in tests to assess their willingness to act.

Participants were asked to make a physical effort to raise money for a climate-based charity, or a charity seeking to end world hunger. Prior to engaging in the physical effort, participants received one from a range of 11 different interventions (or none). The most successful interventions were:

- System justification: Text and images framed climate change as a threat to participants’ way of life and encouraged pro-environmental behaviour as patriotic; and

- Decreasing psychological distance: Climate change was presented as an immediate, local threat, and participants reflected on how it affects them personally.

Interventions that were less successful in overcoming bias include:

- Scientific consensus: Participants saw a message and graphic emphasising that 99% of climate scientists agree climate change is real and caused by humans; and

- Letter to future generations: Participants wrote a letter to a future child or other family member, describing their efforts to protect the planet and how they wish to be remembered.

The research team also found individual predictors of effort to help the environment included their personal belief that climate change is real and support for pro-environmental policies.

Professor Patricia Lockwood from the University of Birmingham and a senior author of the paper said: “As the world prepares to gather for COP30 in Brazil this year, individual and collective citizen action is an essential step towards making a meaningful difference to prevent climate change that affects every part of the world.

“Our findings show that despite how powerful some interventions might feel to sway us on climate action, when it comes to prosocial behaviour we as humans are by and large motivated by what feels immediate and close to us.

“Making climate action a patriotic duty for every citizen in every country around the world is a tool that we can adopt now to try to limit human-caused climate change.”

The study’s authors note that the paper doesn’t look at the difference in interventions between participants from different countries, due to the numbers of people taking part.

The University of Birmingham is leading research to help mitigate and adapt to the risks and impacts associated with climate change. The University has been awarded UNFCCC Observer Status which means that its experts can contribute to the vital discussions taking place at COP30.

***

Research at Birmingham, including at the Birmingham Institute for Sustainability and Climate Action addresses the reality of climate change through transforming health, environment, and society – sustainably supporting people and planet. Its researchers work with industry, academic and policy partners to accelerate progress on UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) towards the 2030 Agenda.

Journal Reference:

Cutler, J., Contreras-Huerta, L.S., Todorova, B. et al., ‘Psychological interventions that decrease psychological distance or challenge system justification increase motivation to exert effort to mitigate climate change’, Communications Psychology 3, 148 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s44271-025-00332-4

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Birmingham

New modelling shows difficult future for the Great Barrier Reef under climate change

A research team led by The University of Queensland simulated different future climate scenarios driven by a range of plausible global emissions trajectories.

Dr Yves-Marie Bozec from UQ’s School of the Environment said the comprehensive modelling of individual corals included their ability to adapt to warmer water, large-scale reef dynamics and their interconnections on ocean currents.

“We ran all of those factors with the most up to date climate projections – and the news was not good,” Dr Bozec said.

“We forecast a rapid coral decline before the middle of this century regardless of the emissions scenario.

“Corals may partially recover after that, but only if ocean warming is sufficiently slow to allow natural adaptation to keep pace with temperature changes.

“Adaptation may keep pace if global warming does not exceed 2 degrees by 2100.

“For that to happen, more action is needed globally to reduce carbon emissions which are driving climate change.”

The ecosystem model, ReefMod-GBR, simulated the lifecycles of multiple coral species on 3,806 individual reefs.

Each modelled reef had tailored environmental settings including water quality, larval connectivity with neighbouring reefs, outbreaks of the coral-eating Crown of Thorns starfish and the risk of cyclones and coral bleaching until 2100.

Professor Peter Mumby said the model was tested extensively against long-term historic monitoring of the Great Barrier Reef to ensure it was as accurate as possible.

Professor Mumby said it showed that the rate of global warming was critical.

“We saw that many reefs could persist under the Paris Agreement target of 2 degrees of warming,” he said.

“However, higher emissions leading to faster temperature rises would drive most reefs to a near collapse.”

The study has a glimmer of hope, even on the current emissions trajectory.

“Importantly, reefs in areas where the water doesn’t heat up so dramatically because it is well mixed, fared better than others,” Professor Mumby said.

“And the better-connected reefs with good access to larval replenishment from other nearby reefs were healthier.

“This shows management efforts to safeguard strategic parts of the coral reef network have a tangible benefit in promoting reef health.

“Reef management remains vitally important even on our current emissions trajectory.”

“The window for meaningful action is closing rapidly but it hasn’t shut,” Dr Bozec said.

“Reducing global emissions and addressing local stressors can still make a difference.”

Executive Director of the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program, Dr Cedric Robillot said the collaborative research within the program shows that the local response of marine ecosystems to ocean warming is complex and nuanced.

“These findings confirm our understanding that coral reefs and the communities they support are facing an existential threat,” Dr Robillot said.

“We must curb greenhouse gas emissions drastically, redouble our current management efforts, and develop new interventions to assist coral reefs while ocean warming is gradually arrested.”

The research is published in Nature Communications.

***

This work was funded by the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program, a partnership between the Australian Government’s Reef Trust and the Great Barrier Reef Foundation. It was completed with collaborators at CSIRO and The Australian Institute of Marine Science.

Journal Reference:

Bozec, YM., Adam, A.A.S., Arellano-Nava, B. et al., ‘A rapidly closing window for coral persistence under global warming’, Nature Communications 16, 9704 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65015-4

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Queensland

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay