Summary:

Understanding past Antarctic ice sheet behaviour relies on oxygen isotope ratios (δ¹⁸O) measured in deep-sea fossils. Traditionally, large Oligocene δ¹⁸O swings, 34–23 million years ago, were interpreted as evidence for repeated growth and retreat of the Antarctic ice sheet. The oxygen isotopic composition of marine calcite (δ¹⁸Ocalcite) normally reflects both ocean temperature and the amount of water stored in ice sheets, but by using clumped isotope thermometry, the study was able to isolate the temperature signal from the δ¹⁸O record.

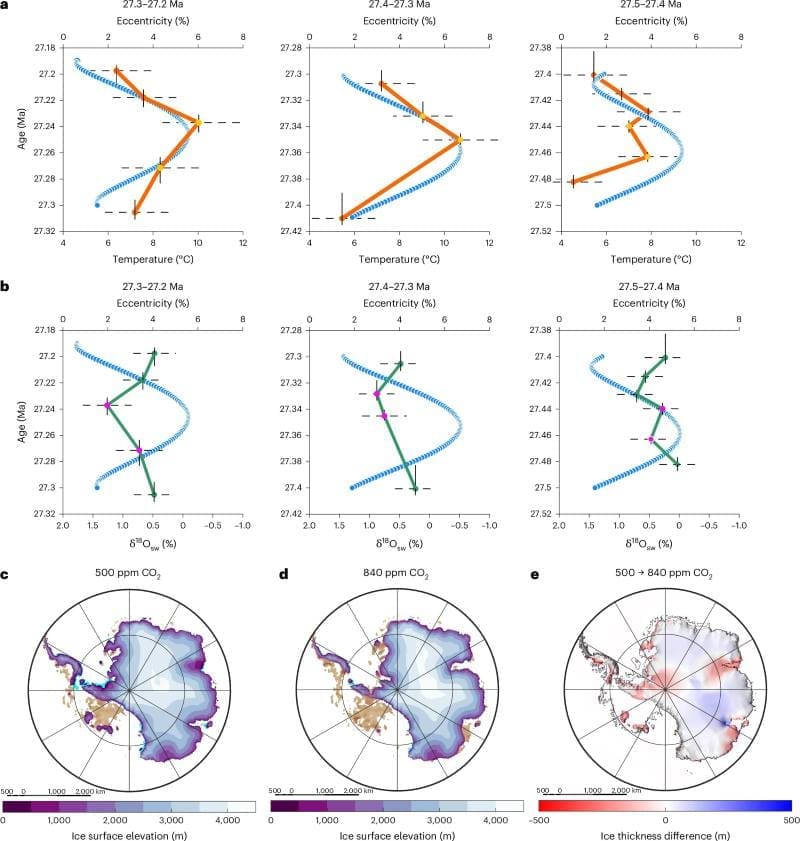

A new study published in Nature Geoscience presents the first orbital-scale reconstruction of deep ocean temperature during the Oligocene. Analyzing fossil benthic foraminifera from deep-sea drill cores, the researchers found temperature fluctuations of up to 4 °C at depths of around 4,000 m. These cycles closely track δ¹⁸O variations and Earth’s orbital eccentricity, demonstrating that abyssal warming and cooling alone can explain the isotope record. Model simulations suggest the Antarctic ice sheet was likely relatively stable during the Oligocene, possibly protected by its higher elevation and limited ocean contact.

— Press Release —

Swinging abyss

The knowledge of climate variability in the geological past is extensively based on the proportion of the heavy oxygen isotope (¹⁸O) in deep ocean marine calcite (δ¹⁸Ocalcite). This is measured on the fossil shells of microscopic organisms that have lived on the ocean floor for hundreds of millions of years and are known as benthic foraminifera. δ¹⁸O reflects a mixture of ocean temperature and continental ice volume and over the past 50-60 years has provided us with a wealth of information for instance about the ice ages of the past 2.6 million of years or the ice-free warm climate of the early Cenozoic 65 to 34 million years ago.

However, one problem with the δ¹⁸O method is that it is not always easy to disentangle from the signal the contribution of temperature and that of ice volume. For instance, in the mid Oligocene, about 28 million years ago, large swings in the oxygen isotope composition of benthic foraminifera with a rhythm of 110,000 years were interpreted as large ice-ages involving the waxing and waning of the Antarctic ice sheet, up to 90 per cent of its current size.

A team led by scientists from University of Bergen (Norway) has now discovered for the first time that the large ups and downs in oxygen isotopes of the mid Oligocene were primarily driven by large temperature changes in the abyssal ocean and not, as previously assumed, to enormous changes in ice volume in Antarctica.

“The temperature in the very deep ocean has been traditionally considered to be relatively stable on multimillennial time scales, as this environment lies thousands of meters below the surfac, somewhat more isolated from climatic drivers that act at the ocean-atmosphere interface,” says Dr Flavia Boscolo-Galazzo, lead author of the study. She began her analyses at University of Bergen and now works at MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences at the University of Bremen.

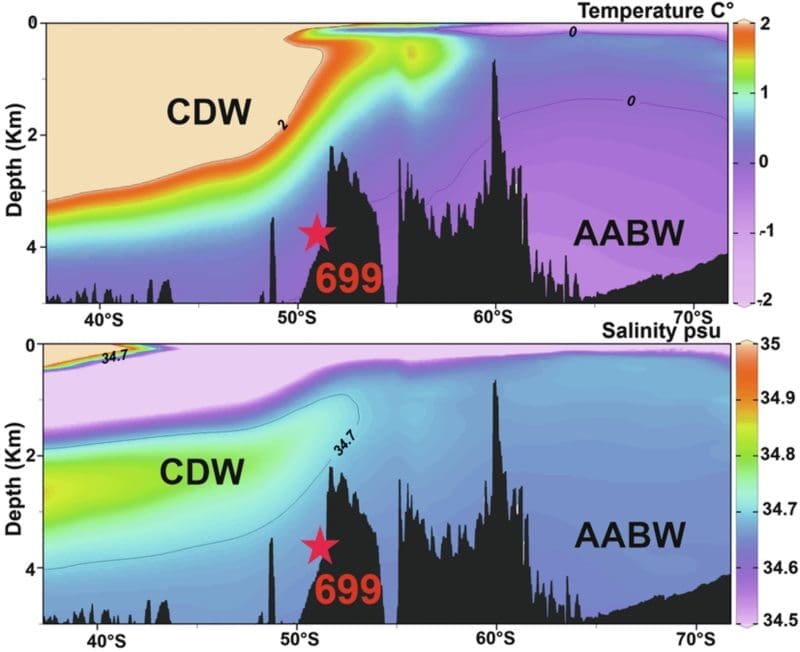

However, using a novel method called clumped-isotope palaeothermometry, the scientists were able to reconstruct large temperature fluctuations – up to 4 degrees Celsius – at a depth of about 4,000 meters in the Southern Ocean. Such fluctuations occurred simultaneously with the fluctuations in oxygen isotopes (δ¹⁸O) as well as changes in Earth’s orbital eccentricity, suggesting a climatic forcing.

“This is an important finding as it shows that, even at such depths, ocean temperature can change significantly in response to climate variability. For this reason, oxygen isotopes from the deep ocean can no longer be interpreted as an indicator of changes in ice volume without independent temperature reconstructions,” explains Dr Flavia Boscolo-Galazzo.

The new temperature reconstructions for the abyssal Southern Ocean, together with computer models, suggest that the ice volume of the Antarctic ice sheet was relatively stable during the Oligocene. “There is evidence that the Antarctic continent was higher above sea level than today and that the ice-sheet probably did not extend into the ocean during the Oligocene. This situation, which differs from today’s configuration, may have protected the ice sheet from the warming influence of the surrounding ocean.”

The team used material from deep-sea drill cores obtained through international ocean drilling programs such as IODP³ (International Ocean Drilling Programme) and predecessor programs and archived in the Bremen Core Collection for their analyses. Fossil benthic foraminiferal shells were extracted from these samples and analyzed for their chemical composition at the FARLAB facility for clumped isotopes at the University of Bergen.

The team concludes that their findings will help to understand how the climate system functions in warmer climates than today.

***

The project was funded by the European Research Council and Norwegian Research Council.

Participating institutions:

MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen (Germany)

Department of Earth Science and Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, University of Bergen (Norway)

Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Manchester (Great Britain)

Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences University of Exeter, Cornwall (Great Britain)

Department of Earth Sciences, University of Milan (Italy)

Instituto Andaluz de Ciencias de la Tierra, Granada (Spain)

Institute of Marine and Environmental Sciences, University of Szczecin (Poland)

Institute of Earth Sciences, Universität Heidelberg (Germany)

Journal Reference:

Boscolo-Galazzo, F., Taylor, V.E., Galaasen, E.V. et al., ‘Oligocene deep ocean oxygen isotope variations primarily driven by temperature’, Nature Geoscience (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41561-025-01878-y

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences | University of Bremen

Featured image credit: Kathryn Rahimzadeh | Unsplash