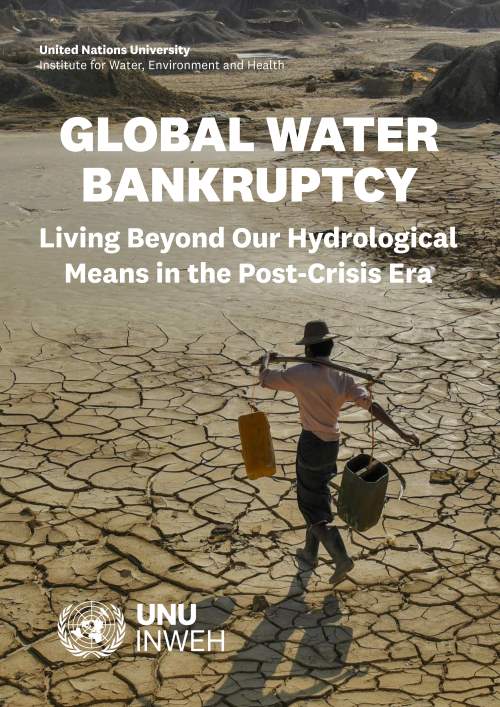

The world has entered what United Nations scientists describe as an era of “global water bankruptcy,” a condition in which decades of overuse, pollution, and environmental degradation have pushed many water systems beyond recovery. A new report by the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health (UNU-INWEH) argues that commonly used terms such as “water stress” and “water crisis” no longer capture the permanence of the damage now unfolding across large parts of the planet.

Titled ‘Global Water Bankruptcy: Living Beyond Our Hydrological Means in the Post-Crisis Era‘, the report frames water use through an accounting lens. It concludes that many societies have exhausted not only their annual renewable water “income” from rivers, soils, and snowpack, but have also depleted long-term “savings” held in aquifers, glaciers, wetlands, and lakes. In a growing number of regions, those reserves have been drawn down so far that returning to historic baselines is no longer realistic.

“This report tells an uncomfortable truth: many regions are living beyond their hydrological means, and many critical water systems are already bankrupt,” says lead author Kaveh Madani, Director of UNU-INWEH. The report is grounded in a peer-reviewed paper that formally defines water bankruptcy as persistent over-withdrawal from surface and groundwater relative to renewable inflows and safe depletion levels, combined with irreversible or prohibitively costly losses of water-related natural capital.

The physical consequences of this long-term overshoot are increasingly visible. Aquifers have become compacted, reducing their storage capacity and causing land subsidence in cities, deltas, and coastal zones. Lakes and wetlands have disappeared across entire regions, while freshwater biodiversity losses are mounting and often permanent. Around 70% of the world’s major aquifers show long-term decline, and more than half of large lakes worldwide have lost water since the early 1990s, affecting roughly one-quarter of the global population that relies on them directly.

The report emphasizes that water bankruptcy is not defined by short-term conditions or annual rainfall. A basin can experience floods and still be water bankrupt if long-term withdrawals exceed replenishment. In that sense, water bankruptcy is presented as an issue of balance, accounting, and sustainability rather than how wet or dry a place appears in a given year.

Several regions illustrate how this post-crisis condition is taking shape. In the Middle East and North Africa, high water stress intersects with climate vulnerability, low agricultural productivity, energy-intensive desalination, and complex political economies. Parts of South Asia are experiencing chronic groundwater decline and land subsidence driven by irrigation and rapid urbanization. In the American Southwest, the Colorado River and its reservoirs have become symbols of water that was over-allocated long before climate pressures intensified.

Globally, the human consequences are extensive. Nearly three-quarters of humanity live in countries classified as water-insecure or critically water-insecure. About 2 billion people live on sinking ground linked to groundwater over-pumping, while some cities experience land subsidence of up to 25 centimeters per year. Agriculture sits at the center of this challenge, accounting for roughly 70% of global freshwater withdrawals and drawing more than 40% of its irrigation water from aquifers that are steadily being drained.

“Millions of farmers are trying to grow more food from shrinking, polluted, or disappearing water sources,” says Madani. “Without rapid transitions toward water-smart agriculture, water bankruptcy will spread rapidly.”

The report argues that the current global water agenda is no longer suited to this reality. Policies focused primarily on drinking water, sanitation, and incremental efficiency gains are described as insufficient in regions where natural water capital has already been irreversibly damaged. Instead, the authors call for a reset that formally recognizes water bankruptcy, strengthens long-term monitoring, and elevates water within climate, biodiversity, development, and peacebuilding frameworks.

Water bankruptcy, the report stresses, is not only a hydrological issue but also a justice and security challenge. The costs of adjustment fall disproportionately on smallholder farmers, Indigenous Peoples, low-income urban residents, women, and youth, while the benefits of overuse have often accrued to more powerful actors.

“Water bankruptcy is becoming a driver of fragility, displacement, and conflict,” says UN Under-Secretary-General Tshilidzi Marwala, Rector of UNU. “Managing it fairly – ensuring that vulnerable communities are protected and that unavoidable losses are shared equitably – is now central to maintaining peace, stability, and social cohesion.”

Despite its stark diagnosis, the report does not frame water bankruptcy as an endpoint. “Declaring bankruptcy is not about giving up, it is about starting fresh,” Madani says. “The longer we delay, the deeper the deficit grows.”

Report in brief

Global condition

- The report concludes that the world has already entered an era of Global Water Bankruptcy, defined as a persistent post-crisis state in which long-term water use and degradation exceed renewable inflows and safe depletion limits.

- While not every basin or country is water-bankrupt, enough critical systems have crossed irreversible thresholds to alter the global risk landscape through trade, migration, climate feedbacks, and geopolitical dependencies.

Surface water and wetlands

- More than 50% of the world’s large lakes have lost water since the early 1990s, affecting about 25% of the global population that relies on them directly.

- Around 410 million hectares of natural wetlands have disappeared over the past five decades, an area almost equal to the size of the European Union.

- The annual value of lost wetland ecosystem services is estimated at US$5.1 trillion.

- Dozens of major rivers now fail to reach the sea for part of the year.

Groundwater and land subsidence

- About 70% of major aquifers worldwide show long-term declines.

- Groundwater provides roughly 50% of global domestic water use and more than 40% of irrigation water.

- Land subsidence linked to groundwater over-pumping affects nearly 2 billion people.

- Some cities are experiencing ground level drops of up to 25 centimeters per year, permanently reducing aquifer storage capacity and increasing flood risk.

Cryosphere and long-term storage

- In several regions, more than 30% of glacier mass has been lost since 1970.

- Entire low- and mid-latitude mountain ranges are expected to lose functional glaciers within decades, undermining long-term water security for downstream populations.

Agriculture and food systems

- Agriculture accounts for about 70% of global freshwater withdrawals.

- About 3 billion people and more than half of global food production are concentrated in areas where total water storage is declining or unstable.

- More than 170 million hectares of irrigated cropland are under high or very high water stress, equivalent to the combined land area of France, Spain, Germany, and Italy.

- Salinization alone has damaged about 100 million hectares of cropland worldwide.

Water insecurity and human exposure

- Nearly 75% of the world’s population live in countries classified as water-insecure or critically water-insecure.

- Around 4 billion people face severe water scarcity for at least one month each year.

- Approximately 2.2 billion people lack safely managed drinking water, while 3.5 billion lack safely managed sanitation.

Drought and economic impacts

- The report identifies a growing pattern of anthropogenic drought, driven by overuse and degradation rather than natural variability alone.

- The current annual global cost of drought is estimated at US$307 billion.

- More than 1.8 billion people lived under drought conditions in 2022–2023.

Time dimension of overuse

- Many river basins and aquifers have been overdrawing their water resources for more than 50 years, depleting long-term natural water capital rather than annual renewable supplies.

Report:

Madani K., ‘Global Water Bankruptcy: Living Beyond Our Hydrological Means in the Post-Crisis Era’ (2026), United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health (UNU-INWEH), Richmond Hill, Ontario, Canada. DOI: 10.53328/INR26KAM001

Journal Reference:

Madani, K., ‘Water Bankruptcy: The Formal Definition’, Water Resources Management 40, 78 (2026). DOI: 10.1007/s11269-025-04484-0

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by The United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health (UNU-INWEH)

Featured image credit: Pyae Phyo Aung | Pexels