Summary:

Milk production falls sharply during heatwaves – even on high-tech dairy farms where cows are kept cool. A new study published in Science Advances finds that extreme humid heat can reduce milk yields by up to 10 percent, and common cooling systems like fans and sprinklers only recover about half of that loss. Drawing on more than 320 million daily observations over 12 years from Israel’s advanced dairy sector, the study is among the most comprehensive to date on how heat stress affects dairy cattle.

The researchers found that losses are greatest during cows’ most productive periods and that recovery can take more than 10 days after a hot spell. Even in Israel, where nearly every farm has already adopted some form of cooling, extreme heat continues to take a toll. “Even the most high-tech, well-resourced farms are deploying adaptation strategies that may be an insufficient match to climate change,” says study co-author Eyal Frank of the University of Chicago.

The research suggests that average daily milk output could drop by 4 percent globally by mid-century, with countries like India, Pakistan and Brazil especially affected. Despite clear economic benefits to cooling, the study highlights the biological limits of adaptation in livestock systems already operating near the technological frontier.

Climate change cuts milk production, even when farmers cool their cows

While recent studies have shown climate change will cut crop production, there has been less research into its impacts on livestock. Dairy farmers already know their cows are vulnerable to heat. What will more heat mean? In one of the most comprehensive assessments of heat’s impact on dairy cows, a study in the journal Science Advances finds one day of extreme heat can cut milk production by up to 10 percent. The effects of that hot weather can last more than 10 days later, with efforts to keep cows cool being insufficient.

“Climate change will have wide-ranging impacts on what we eat and drink, including that cold glass of milk,” says one of the study’s co-authors Eyal Frank, an assistant professor at the Harris School of Public Policy. “Our study found that extreme heat leads to significant and lasting impacts on milk supply, and even the most high-tech, well-resourced farms are deploying adaptation strategies that may be an insufficient match to climate change.”

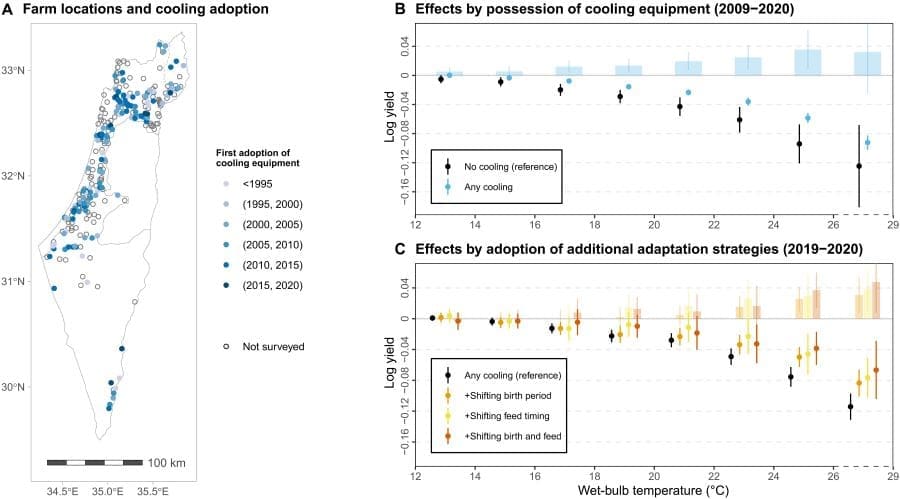

Frank and his co-authors Claire Palandri, Ayal Kimhi, Yaniv Lavon, Ephraim Ezra, and Ram Fishman studied the dairy industry in Israel, an advanced dairy system representative of top milk producing countries. The researchers analyze highly local weather data to measure humid heat’s impact on more than 130,000 Israeli dairy cows over 12 years. They then surveyed more than 300 dairy farmers to see how much cooling technologies have helped.

“The dairy industry in Israel is a good testbed because farms are scattered throughout the country and experience a wide range of temperatures and humidity that represent conditions for top milk producing countries around the world,” says co-author Ram Fishman, an associate professor of Public Policy at Tel Aviv University. “Plus, almost all farmers have already adopted ventilation and spraying systems to keep their cows cooler. What’s more, Israeli dairy farms are some of the most technologically advanced in the world, so whatever impacts they suffer are likely greater in other regions.”

The team of researchers found that milk production declined significantly on hot, humid days – by up to 10 percent when wet-bulb temperatures exceeded 26 °C (78.8 °F). Wet-bulb temperatures combine information on dry-bulb temperature (the ambient air temperature) and humidity. By doing so, they offer a measure that better captures heat stress. The same ambient air temperature feels very different on dry or on humid days for people and cows.

When cows are exposed to this humid heat, often referred to as “steam bath” conditions, it takes more than 10 days for milk production to bounce back to normal levels. While nearly all of the farms the researchers surveyed had adopted cooling technologies, these efforts to adapt only offset about half of the losses on 20 °C days (68 °F). The hotter it gets, the less they help. On 24 °C (75.2 °F), they offset 40 percent of the losses. Still, the researchers find it is worth it to install cooling equipment, with farmers able to recoup the costs of installing the equipment in about a year and a half.

“Dairy farmers are well aware of the negative impacts that heat stress has on their herds, and they use multiple forms of adaptation,” says co-author Ayal Kimhi, associate professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and vice president of the Shoresh Institution for Socioeconomic Research. “Adaptation is costly, and farmers need to carefully balance the benefits they obtain versus the costs. This is why we see some investment in cooling measures, but not a complete insulation of cows from their environment, which would be far too costly to implement.”

The researchers use their estimates in Israel to show how climate change could affect milk production globally by mid-century, and which countries benefit the most from adaptation. They find that, without cooling, the top 10 milk-producing countries could see average daily milk output decline by 4 percent – with some countries impacted more than others. Three out of the top five producers – India, Pakistan and Brazil – see greater losses than Israel: between 3.5 percent and 4 percent per cow per day. They are also the countries that benefit the most from cooling. Yet, even with cooling, the five largest producers (including the United States and China) still see losses between 1.5 percent and 2.7 percent per cow per day.

“Our research underscores the value and the limitations of cooling technologies and other efforts taken by dairy farmers to adapt to climate change,” says lead-author Claire Palandri, a postdoctoral scholar at the Harris School of Public Policy. “Policymakers should look into more strategies to not only cool cows but reduce stressors, like confinement and calf separation. Stressors make cows more sensitive to heat and less resilient.”

Journal Reference:

Claire Palandri, Eyal G. Frank, Ayal Kimhi, Yaniv Lavon, Ephraim Ezra and Ram Fishman, ‘High-frequency data reveal limits of adaptation to heat in animal agriculture’, Science Advances 11, eadw4780 (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adw4780

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Featured image credit: Roy Buri | Pixabay