Summary:

Ancient global warming offers important clues about how rainfall may behave in a much hotter future, according to a new study published in Nature Geoscience. By examining the early Paleogene period, around 66 to 48 million years ago, researchers reconstructed how precipitation responded when Earth’s climate was far warmer than today and atmospheric carbon dioxide levels were two to four times higher.

The international team combined climate modelling with geological “proxies” preserved in plant fossils, ancient soils and river deposits. Rather than focusing only on yearly rainfall totals, the study examined how often rain fell and how intense it was. The results show that precipitation during extreme warming became far more irregular. Polar regions were generally wet and even monsoonal, while many mid-latitude and continental interiors experienced long dry periods interrupted by intense downpours.

Crucially, these shifts began millions of years before the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) and persisted long after it ended. The findings suggest that extreme warmth can alter rainfall patterns in nonlinear ways, with timing and variability playing a larger role than average precipitation, challenging assumptions built into many climate models.

— Press Release —

What past global warming reveals about future rainfall

To understand how global warming could influence future climate, scientists look to the Paleogene period that began 66 million years ago, covering a time when Earth’s atmospheric carbon dioxide levels were two to four times higher than they are today.

New research by the University of Utah and the Colorado School of Mines reconstructs how rainfall responded to extreme warming during this period using “proxies,” or clues left in the geological record in the form of plant fossils, soil chemistry and river deposits. The results challenge the commonly held view that wet places get wetter when the climate warms and drier places become drier, according to co-author Thomas Reichler, professor of atmospheric sciences at the U.

“There are good reasons, physical reasons for that assumption. But now our study was a little bit surprising in the sense that even mid-latitudes regions tended to become drier,” Reichler said. “It has to do with the variability and the distribution of precipitation over time. If there are relatively long dry spells and then in between very wet periods—as in a strongly monsoonal climate—conditions are unfavorable for many types of vegetation.”

Rainfall was far more variable

Instead of focusing on the amount of precipitation each year, Reichler’s team explored when rain fell and how often. They found rainfall appears to be much less regular under extreme warming, often occurring in intense downpours separated by prolonged dry spells.

The researchers concluded polar regions were wet, even monsoonal, during the Paleogene, while many mid-latitude and continental interiors became drier overall.

The findings, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, are based on a comprehensive analysis of existing research. To conduct the study, Reichler teamed up with Colorado School of Mines geologists, who analyzed proxy data from the fossil record, while Reichler conducted the climate modeling with graduate student Daniel Baldassare.

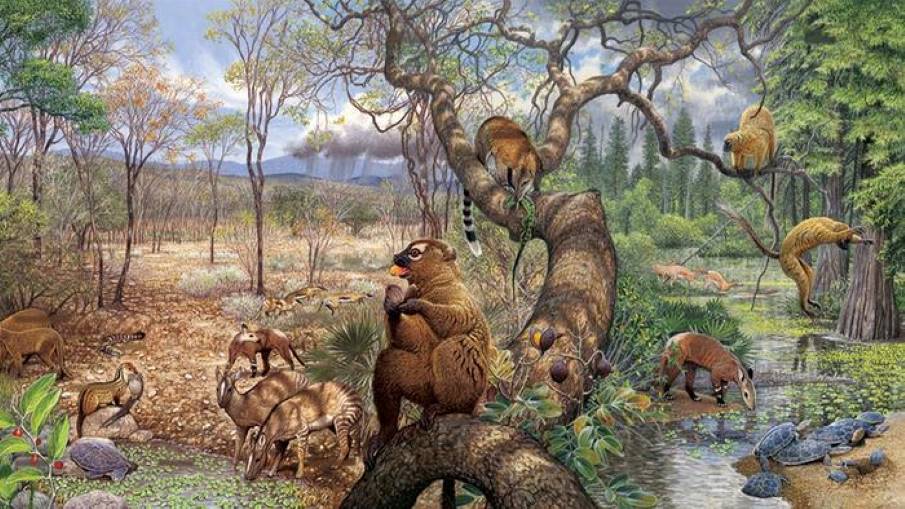

This study looks back to the warmest time in Earth’s history, the early Paleogene, 66 to 48 million years ago, to understand how rainfall behaves when the planet gets very hot. This period began with the sudden demise of the dinosaurs and saw the rise of mammals in terrestrial ecosystems. This was the time when some of Utah’s notable landscapes, such as the hoodoos of Bryce Canyon and the badlands of the Uinta Basin, were deposited.

It was also a period of intense warming culminating in the well-studied event called the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, or PETM, when levels of heat were 18 degrees Celsius (32 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than they were just before humans began releasing greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere. Some scientists consider the climate of this period a possible worst-case scenario for future climate change.

Proxies in the fossil record

Since it is not possible to measure precipitation that occurred millions of years ago, scientists examine evidence in the geologic record to draw conclusions about ancient climates. In this case, Reichler’s Colorado colleagues looked at plant fossils and ancient soils.

“From the shape and size of fossilized leaves, you can infer aspects of climate of that time because you look at where similar plants exist today with those leaves. So this would be a climate proxy. It’s not direct measurement of temperature or humidity; it’s indirect evidence for climate of that time,” Reichler said.

Another example is the geomorphology of the landscape, such as river channels.

“When there is intermittent, strong precipitation then followed by long periods of drought, that precipitation is forming the riverbed in different ways because there’s very high amounts of water flowing down and carving it out or transporting the rocks much more vigorously than were it a little drizzle every day,” he said.

These reconstructions are inherently uncertain because they rely on indirect evidence rather, Reichler cautioned, but they provide the best available information about how climate operated under extreme warming.

Understanding Earth’s ancient climates enables scientists to better evaluate how well models predict climate behavior under conditions different from the present. Comparisons with paleoclimate model simulations indicate today’s models underestimate how irregular rainfall can become during extreme warming, according to Reichler.

The dry conditions documented in the study were often caused not by less total rainfall, but by shorter wet seasons and longer gaps between rain events. These patterns began millions of years before the PETM and lasted long after, suggesting that once Earth’s climate system crosses certain thresholds, rainfall behavior can change in surprising and complicated ways.

For a warming world, in other words, the timing and reliability of rain may matter more than yearly averages, and that has important implications for ecosystems, floods, droughts and water management.

Journal Reference:

Slawson, J.S., Plink-Bjorklund, P., Reichler, T. et al., ‘More intermittent mid-latitude precipitation accompanied extreme early Palaeogene warmth’, Nature Geoscience 19, 120–127 (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41561-025-01870-6

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Brian Maffly | University of Utah

Featured image credit: Steve Gribble | Unsplash