Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press roundup (February 6, 2026), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

— Press Release —

Learning from the Global South: How do people cope with heat?

Climate change presents tremendous challenges, especially for people in the Global South. Two international studies led by Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin have investigated how the population in sub-Saharan Africa is coping with rising temperatures and the threat of infection – and what can be done about it.

Reporting in the journals The Lancet Planetary Health and Nature Medicine, the researchers relate that women in agriculture suffer more from rising temperatures, while simple measures can improve domestic living conditions. The results are also relevant for adapting to climate change in Germany.

Heat and drought present major problems for farmers. Not only due to the fact that their plants wither and their animals die of thirst. “In sub-Saharan Africa in particular, farmers spend many hours in the fields, putting themselves at great risk,” reports Dr. Martina Maggioni, who heads the Topic of Climate Change and Health at the Charité Center for Global Health. “We wanted to find out how the women and men in Burkina Faso, one of the poorest countries in the world, are coping with the rising temperatures.”

People adapt – if possible

An international study led by Martina Maggioni, which also included scientists from Burkina Faso, Kenya and the University of Heidelberg, provided 39 women and 39 men with wearable measuring devices. The team recorded the ambient temperature and humidity, in addition to the physical activity, body temperature and pulse of the subsistence farmers for over a year. “This allowed us to calculate how physically demanding the work was and how it impacted on their health,” reports Maggioni.

It emerged that specifically women could not adapt their activities in the field well to the increasing heat. “The men could shift their work to the early morning or late evening hours or even to the cooler months. We haven’t seen that with women, who often also take care of the household, putting them especially at risk from the rising temperatures.” Maggioni hopes that the results will now be used for early warning systems and the protection of outdoor workers. As temperatures continue to rise, however, the adaptations reach their limits in sub-Saharan Africa and food safety could be endangered.

Simple measures delivering major impact

The second project, jointly led by Dr. Bernard Abong’o from the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) and Martina Maggioni, focused on the housing situation: “Here in Kenya, the rural population mostly lives in mud houses and is extremely impacted by both the rising temperatures and the mosquitoes that transmit malaria,” as Bernard Abong’o stated.

Simple, affordable measures are called for: as it was shown, simple home modifications, as for example white-painted roofs combined with the installation of insect screens on all open eaves, doors and windows greatly improved the living conditions after a relatively short period of time: Indoors, both the temperature and the number of mosquitoes dropped significantly. “Almost all households wanted to take part because the measures were cheap and effective,” reports Maggioni. Now they are to be extended to other parts of Kenya and even to other countries in southern Africa.

Results also relevant for Germany

The results of the two studies are also interesting for Germany: Because temperatures are also on the rise in this country, farmers and workers need to be protected both indoors and outdoors. “Air conditioning systems are not the solution: We need affordable and sustainable measures to adapt our cities and buildings to the current environmental changes,” demands Maggioni.

As Prof. Beate Kampmann, Scientific Director of the Charité Center for Global Health, emphasizes, neither climate change nor health or disease know national borders: “This is why research into global health is so crucial: We can learn from people in the Global South today, because they are already confronted with what we will be facing in the near future. While we are already very advanced in terms of diagnostics and therapy in Germany, there is still a lot to do in terms of prevention.”

Journal Reference:

Eggert E et al., ‘Physical effort during labour and behavioural adaptations in response to heat stress among subsistence farmers in Burkina Faso: a gender-specific longitudinal observational study’, Lancet Planet Health 9, 12: 101344 (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.lanplh.2025.101344

Abong’o, B., Kwaro, D., Bange, T. et al., ‘Housing modifications for heat adaptation, thermal comfort and malaria vector control in rural African settlements’, Nature Medicine (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41591-025-04104-9

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin

— Press Release —

Humidity-resistant hydrogen sensor can improve safety in large-scale clean energy

Wherever hydrogen is present, safety sensors are required to detect leaks and prevent the formation of flammable oxyhydrogen gas when hydrogen is mixed with air. It is therefore a challenge that today’s sensors do not work optimally in humid environments – because where there is hydrogen, there is very often humidity. Now, researchers at Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, are presenting a new sensor that is well suited to humid environments – and actually performs better the more humid it gets.

“The performance of a hydrogen gas sensor can vary dramatically from environment to environment, and humidity is an important factor. An issue today is that many sensors become slower or perform less effectively in humid environments. When we tested our new sensor concept, we discovered that the more we increased the humidity, the stronger the response to hydrogen became. It took us a while to really understand how this could be possible,“ says Chalmers doctoral student Athanasios Theodoridis, who is the lead author of the article published in the journal ACS Sensors.

Hydrogen is an increasingly important energy carrier in the transport sector and is used as a raw material in the chemical industry or for green steel manufacturing. In addition to water being constantly present in ambient air, it is also formed when hydrogen reacts with oxygen to generate energy, for example in a fuel cell that can be used in hydrogen-powered vehicles and ships. Furthermore, fuel cells themselves require water to prevent the membranes that separate oxygen and hydrogen inside them from drying out.

Facilities where hydrogen is produced and stored are also constantly in contact with the surrounding air, where humidity varies greatly over time depending on temperature and weather conditions. Therefore, to ensure that the volatile hydrogen gas does not leak and create flammable oxyhydrogen, reliable humidity-tolerant sensors are needed here as well.

The sensor causes the humidity to ‘boil away’

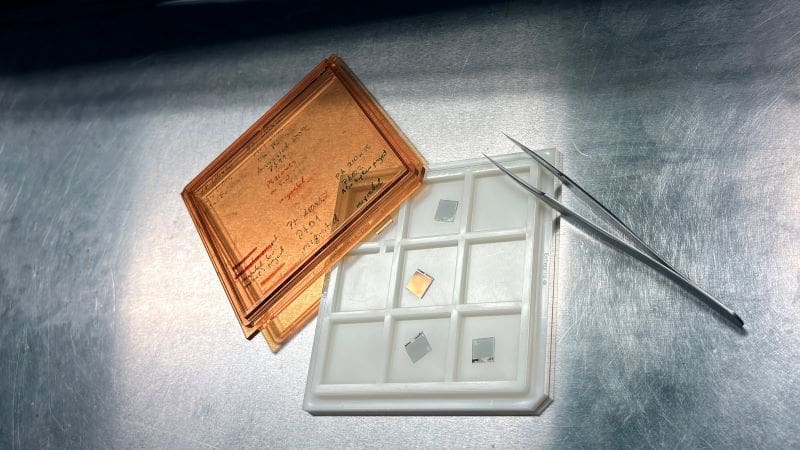

The new humidity-tolerant hydrogen sensor from Chalmers fits on a fingertip and contains tiny particles – nanoparticles – of the metal platinum. The particles act as both catalysts and sensors at the same time. This means that the platinum accelerates the chemical reaction between hydrogen and oxygen from the air, which leads to heat development that causes the humidity, in the form of a film of water on the sensor surface, to ‘boil away’.

The amount of hydrogen in the air determines how much of the water film boils away, and the moisture content in the air controls the thickness of the film. It is therefore possible to measure the concentration of hydrogen by measuring the thickness of the water film. And since the thickness of the water film increases as the air becomes more humid, the sensor’s efficiency increases at the same rate.

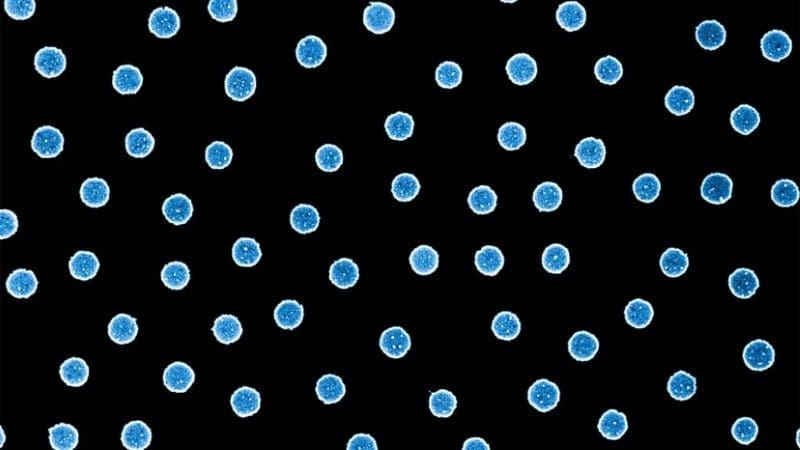

The result of this process can be observed using an optical phenomenon called plasmons, where the platinum nanoparticles capture light and give them a distinct colour. When the concentration of hydrogen gas in the environment changes, the nanoparticles change colour, and at critical levels the sensor triggers an alarm.

At Chalmers, the development of plasmonic hydrogen gas sensors has been under way for many years. Professor Christoph Langhammer’s research team has made several major breakthroughs in the field in terms of sensor speed and sensitivity, as well as the ability to optimise sensor response and humidity resistance using AI. Previously, the group based its sensors on nanoparticles of the metal palladium, which absorbs hydrogen in much the same way as a sponge absorbs water.

The new platinum-based concept, developed within the framework of the TechForH2 competence centre at Chalmers, has led to the creation of a new type of sensor – a “catalytic plasmonic hydrogen gas sensor” – which opens up new possibilities.

“We tested the sensor for over 140 hours of continuous exposure to humid air. The tests showed that it is stable at various given degrees of humidity and can reliably detect hydrogen gas in these conditions, which is important if it is to be used in real-world environments,” says Theodoridis.

The energy transition is placing greater demands on sensors

According to the researchers’ measurements, the sensor detects hydrogen down to the ‘parts per million’ range: 30 ppm – that is, three thousandths of a per cent, making it one of the world’s most sensitive hydrogen gas sensors in humid environments.

“There is currently strong demand for sensors that perform well in humid environments. As hydrogen plays an increasingly important role in society, there are growing demands for sensors that are not only smaller and more flexible, but also capable of being manufactured on a large scale and at a lower cost. Our new sensor concept satisfies these requirements well,” says Christoph Langhammer, Professor of Physics at Chalmers and one of the founders of the sensor company Insplorion, where he now serves in an advisory capacity.

He also recognises that more than one type of material may be required for future hydrogen gas sensors to function in all types of environments.

“We expect to need to combine different types of active materials to create sensors that perform well regardless of the environment. We now know that certain materials provide speed and sensitivity, while others are better able to withstand humidity. We are now working to apply this knowledge going forward,” says Langhammer.

Journal Reference:

Athanasios Theodoridis, Carl Andersson, Sara Nilsson, Joachim Fritzsche, and Christoph Langhammer, ‘A Catalytic-Plasmonic Pt Nanoparticle Sensor for Hydrogen Detection in High-Humidity Environments’, ACS Sensors 10 (11), 8983-8994 (2025). DOI: 10.1021/acssensors.5c03166

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Mia Halleröd Palmgren | Chalmers University of Technology (Chalmers)

— Press Release —

Forest soils increasingly extract methane from atmosphere

Forest soils have an important role in protecting our climate: they remove large quantities of methane – a powerful greenhouse gas – from our atmosphere. Researchers from the University of Göttingen and the Baden-Württemberg Forest Research Institute (FVA) evaluated the world’s most comprehensive data set on methane uptake by forest soils. They discovered that under certain climate conditions, which may become more common in the future, their capacity to absorb methane actually increases.

The data is based on regular measurements at 13 forest plots in south-western Germany over periods of up to 24 years. The study found forest soils absorb an average of three percent more methane per year. The researchers attribute this to the climate: declining rainfall leads to drier soils which methane penetrates more easily than moist soils. In addition, microorganisms break down methane more quickly as temperatures rise.

The results were published in Agricultural and Forest Meteorology.

The researchers measured methane uptake by the soil. They measured soil gas profiles which reflect the chemical composition of the air in the soil at various depths. The data set comes from the FVA’s soil gas monitoring programme. Over a period of many years, samples of air from the soil were taken every two weeks using thin tubes inserted into the earth and analysed in the laboratory. The researchers verified their calculations with independent measurements which involved placing an airtight measuring chamber on the soil surface. If the concentration of a gas such as methane decreases inside the chamber, it is possible to calculate whether and how much gas is being absorbed by the soil.

The data revealed significant differences between the locations studied. Overall, however, it showed that forest soils in south-western Germany absorb large amounts of methane from the atmosphere – especially when annual rainfall decreases and temperatures rise.

“Our long-term data shows that climate change does not necessarily have a negative impact on how much methane forest soils absorb. While the largest study to date from the US found a decline in methane uptake of up to 80 per cent due to increasing rainfall, our significantly more comprehensive field study in south-western Germany found the opposite,” explains Professor Martin Maier at Göttingen University’s Department of Crop Sciences, who led the study and was previously involved in the FVA’s soil gas monitoring programme.

“We observed a significant long-term increase in methane uptake in the forest areas we studied.” Dry soils contain more air-filled pores than wet soils. This makes it easier for methane to penetrate the soil. At the same time, microorganisms break down methane in the soil slightly faster when it gets warmer.

The results contradict current international meta-analyses.

These studies, in which researchers summarise the results of many investigations, tend to conclude that methane uptake in forest soils is decreasing. According to the researchers, their recently published study highlights the importance of considering the data at different areas and regions over a long time period. “Our results make it clear that taking a series of measurements over many years and running monitoring programmes are indispensable for assessing the real effects of climate change,” says Maier.

Journal Reference:

Verena Lang, Valentin Gartiser, Peter Hartmann, Martin Maier, ‘Trend analysis of methane uptake in 13 forest soils based on up to 24 years of field measurements in south-west Germany’, Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 375, 110823 (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2025.110823

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Melissa Sollich | University of Göttingen

— Press Release —

Experts show how major UK food crisis might occur

A new report has set out how the UK might respond to major disruptions to food supplies triggered by events such as war, extreme weather or cyber-attacks – and what can be done now to prevent such disruptions from escalating into a crisis.

Involving 39 experts from institutions including Anglia Ruskin University (ARU) and the University of York, the study maps how shocks to the food system, such as sudden price hikes or food shortages, could intensify pressure on already vulnerable parts of the system, ultimately increasing strain, instability and the risk of social unrest.

Recent events have served as a wake-up call. From cyber-attacks disrupting major retailers like M&S and Co-op, to the global price shocks caused by the war in Ukraine, the dependence of the UK food system on fragile, just-in-time networks has been laid bare.

Published in the journal Sustainability and funded by the British Academy, the Royal Academy of Engineering and the Royal Society, the study argues that long-standing structural issues are leaving the UK dangerously exposed. Addressing these weaknesses, the researchers say, is critical to improving national food resilience.

The report outlines how a major international conflict could lead to trade disruptions, surging energy prices, disrupted agricultural and food supply chains, and escalating food costs. Rising prices would disproportionately affect low-income households, restricting access to nutritious food and heightening food insecurity.

This, in turn, could fuel social tensions and lead to increases in food fraud and sales on the black market, which could result in more food-related illnesses. In a worst-case scenario, public trust in government and business could erode to the point of unrest or riots.

To reduce these risks, the researchers recommend key interventions, including increasing UK energy security, diversifying food value chains, and promoting more varied and resilient diets.

The report also explores how other triggers, such as cyber-attacks or extreme weather events, could cause similar cascading crises, either independently or in combination.

Based on interviews with more than 30 food system experts from academia, government and industry, the study identifies key systemic weaknesses, crisis triggers and interventions that could prevent them.

It also presents a detailed, interconnected map of the UK food system, which is a new tool already being used by policymakers to guide more resilient decision-making.

Professor Sarah Bridle, Chair of Food, Climate and Society at the University of York, said: “The stability of the UK’s food system is a critical aspect of national security. While we can’t always prevent future shocks, we can build resilience to withstand them, and stop a bad situation from becoming a crisis.

“While there is a growing awareness of the potential risks, not enough coordinated work is being done to address the weak spots in the system, and how people are likely to be affected. Understanding how the system might react to extreme pressure is the first step to preventing worst-case scenarios unfolding in the future.”

Professor Aled Jones, Director of the Global Sustainability Institute at Anglia Ruskin University (ARU), said: “The potential for events to trigger a food crisis is frequently underestimated.

“The UK is not immune to disruptions that can lead to severe consequences. Policymakers must adopt a long-term perspective to policy planning, and work across departments and wider food system stakeholders to ensure a whole-systems approach to addressing the problems.”

Dominic Watters, a lived experience researcher, writer and a contributor to the study, said: “Food crises and civil unrest don’t come from a lack of calories alone; they come from a lack of dignity, voice and care. This research highlights how the stigma and dehumanisation of food insecurity are already creating cracks in our society.

“If we want a genuinely resilient and ‘ready’ United Kingdom, we cannot build it on systems of shame. That is why the study speaks to the importance of co-designing responses with communities disproportionately affected, rather than simply deciding for them.”

Journal Reference:

Bridle S, Smith E, Jones A, Falloon P, Pilley V, Hasnain S, Stanbrough L, Vogel C, Douglas C, Doherty B, et al., ‘Potential Pathways and Solutions to Acute Food System Crisis in the UK’, Sustainability 18 (3): 1342 (2026). DOI: 10.3390/su18031342

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Jon Green | Anglia Ruskin University (ARU)

Featured image credit: Freepik (AI Gen.)