Methane emissions from agriculture and fossil fuels were the main drivers behind the renewed rise in global methane concentrations after 2006, even as the atmosphere became more efficient at removing the gas, according to a modeling study published in AGU Advances.

After a period of relative stability between 1999 and 2006, atmospheric methane began increasing again in 2007. To understand why, researchers used a global chemistry-climate model constrained by both methane concentration measurements and carbon isotope observations covering 1980 to 2017. Their results show that emission increases were large enough to outweigh stronger chemical removal in the atmosphere.

Methane sources and the 1980–2017 global budget

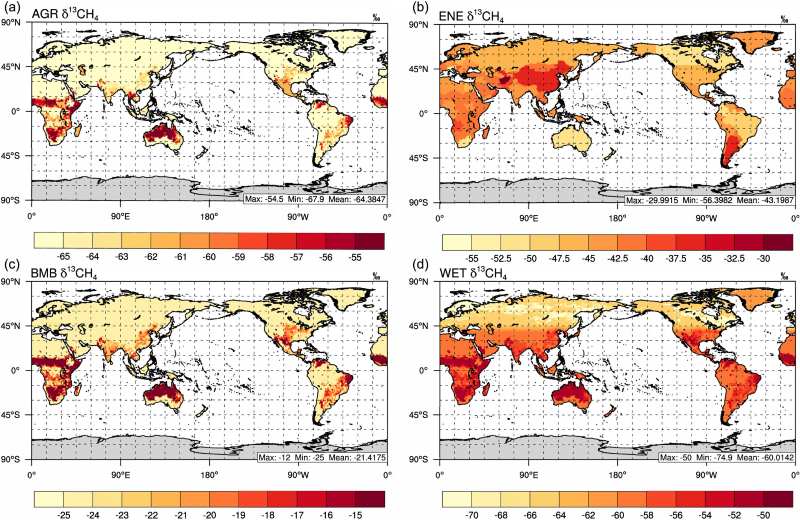

Methane comes from three major source types. Biogenic sources are produced by microbial activity – including wetlands, rice cultivation, landfills and ruminant livestock – and typically carry lighter carbon isotopic signatures. Thermogenic sources originate from the thermal breakdown of organic matter, primarily during fossil fuel extraction and use. Pyrogenic sources result from biomass burning and tend to have heavier isotopic signatures. Because these sources differ isotopically, long-term measurements of δ¹³CH₄ help track shifts in their relative importance. (Note: δ¹³CH₄ measures the ratio of heavy to light carbon in methane, helping researchers identify whether emissions come mainly from microbial sources, fossil fuels, or biomass burning.)

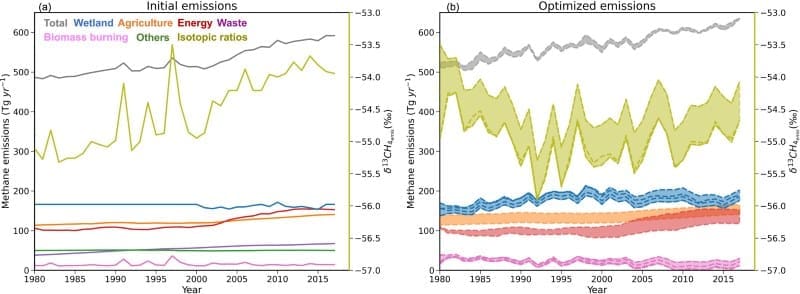

Across the full 1980–2017 period, global methane emissions increased substantially. Model-optimized emissions rose from about 521 teragrams per year in the 1980s to 607 teragrams per year in 2007–2017. Over the same period, methane sinks also strengthened, largely due to changes in the hydroxyl radical, or OH, the main chemical agent that removes methane from the atmosphere. By 2007–2017, total methane removal had risen to roughly 589 teragrams per year.

Why global methane emissions increased after 2006

The post-2006 period marks a distinct phase. Between 1999–2006 and 2007–2017, total emissions increased by around 40 teragrams per year in the baseline simulation. Emissions from agriculture and waste management rose markedly, especially in tropical regions. Fossil fuel emissions also increased across most latitude bands, reinforcing the upward trend.

In contrast, biomass burning emissions declined over the same period, and optimized wetland emissions showed only small global decreases. This combination of rising agricultural and fossil fuel emissions, alongside falling biomass burning, helps explain the renewed methane growth.

Carbon isotope measurements provide an additional constraint. After 2006, atmospheric δ¹³CH₄ shifted toward more negative values, indicating a greater influence from isotopically lighter sources. The model reproduces this shift through increases in tropical agricultural and waste emissions and decreases in isotopically heavier biomass burning, combined with changes in atmospheric chemistry. Although fossil fuel emissions rose, their relatively heavier isotopic signature would, by itself, tend to shift δ¹³CH₄ in the opposite direction. The observed trend reflects the net balance among multiple changing sources and sinks.

A key feature of the study is its explicit simulation of OH and its interaction with methane. The model shows an increasing OH trend over recent decades, which enhanced methane removal. From 1999–2006 to 2007–2017, methane sinks rose by more than 20 teragrams per year. This means that not every increase in emissions leads directly to higher atmospheric concentrations. For methane levels to continue rising after 2006, growth in agricultural and fossil fuel emissions had to exceed the strengthening chemical sink.

The analysis also highlights methane–OH feedback. Higher methane concentrations tend to reduce OH levels, which in turn lengthens methane’s atmospheric lifetime. The study finds that this feedback has intensified over time, implying greater sensitivity of methane concentrations to emission changes than in earlier decades.

Conclusions

Overall, the findings indicate that the renewed methane surge since 2006 is best explained by rising emissions from agriculture and fossil fuels, partly offset by declining biomass burning and shaped by evolving atmospheric chemistry. The results suggest that interpreting recent methane trends requires accounting not only for emission changes but also for shifts in the atmosphere’s capacity to remove the gas.

Journal Reference:

He, J., Naik, V., & Horowitz, L. W., ‘Interpreting changes in global methane budget in a chemistry-climate model constrained with methane and isotopic observations’, AGU Advances 7, (1): e2025AV001822 (2026). DOI: 10.1029/2025AV001822

Article Source:

Peer-reviewed study published in AGU Advances

Featured image: Livestock agriculture and fossil fuel infrastructure are among the main human-driven methane sources identified in recent research. Credit: Muser Press (AI Gen.)