Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press daily roundup (May 9, 2025), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

Will you live an unprecedented life?

Climate extremes, including heatwaves, crop failures, river floods, tropical cyclones, wildfires and droughts, will intensify with continued atmospheric warming. Today’s children will endure more climate extremes then any previous generation.

“In 2021, we demonstrated how children are to face disproportionate increases in extreme event exposure – especially in low-income countries. Now, we examined where the cumulative exposure to climate extremes across one’s lifetime will far exceed that which would have been experienced in a pre-industrial climate,” says Wim Thiery, professor of climate science at VUB and senior author of the study.

“In this new study, living an unprecedented life means that without climate change, one would have less than a 1-in-10,000 chance of experiencing that many climate extremes across one’s lifetime,” says Dr. Luke Grant, lead author and climate scientist at the VUB and Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC). “This is a stringent threshold that identifies populations facing climate extremes far beyond what could be expected without man-made climate change.” The threshold varies by location and type of climate extreme.

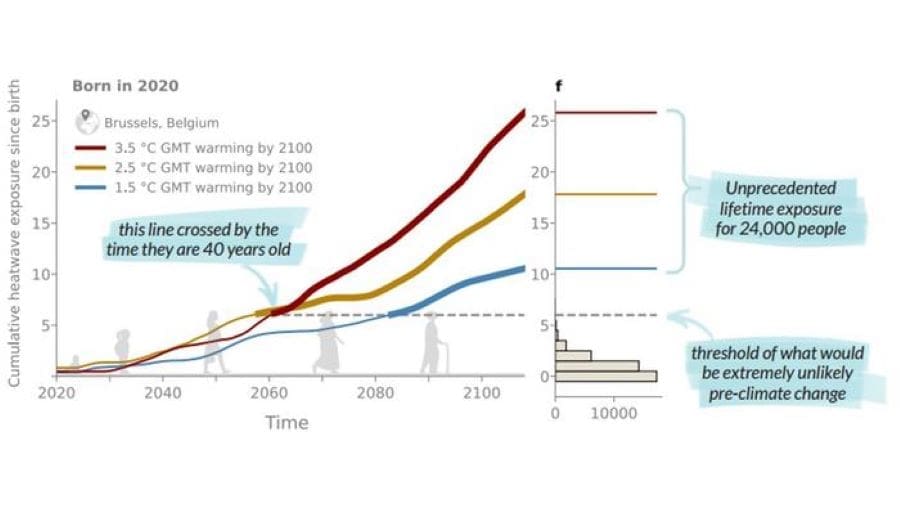

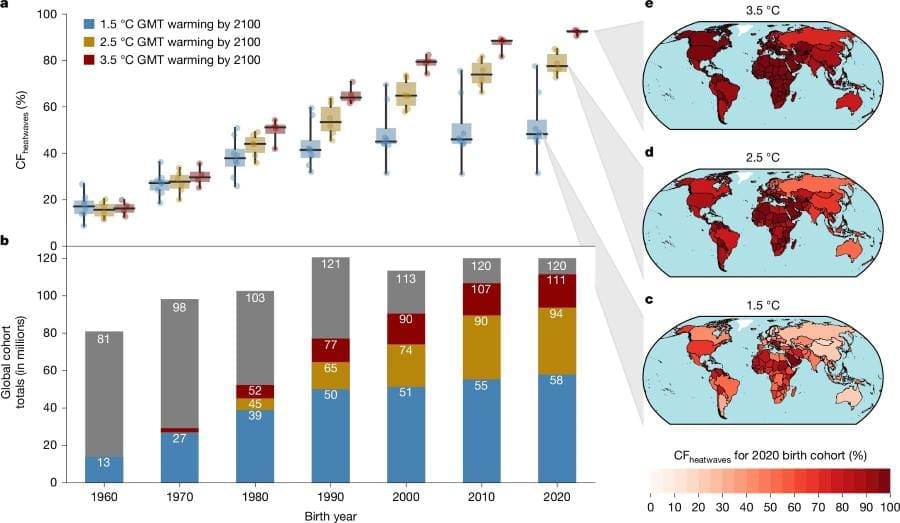

By combining demographic data and climate model projections of climate extremes for each location on earth, the researchers calculated the percentage of each generation born between 1960 and 2020 who will face unprecedented exposure to climate extremes in their lifetime (see Figure 1).

Generational impact of climate change

The younger a person is, the higher their likelihood of unprecedented exposure to climate extremes. Even if we successfully limit global warming to 1.5°C, 52% of children born in 2020 will face unprecedented heatwave exposure, compared to only 16% of those born in 1960. For heatwaves, the effect is particularly pronounced for those born after 1980, when climate change scenarios increasingly dictate exposure levels.

“By stabilizing our climate around 1.5 °C above pre-industrial temperatures, about half of today’s young people will be exposed to an unprecedented number of heatwaves in their lifetime. Under a 3.5 °C scenario, over 90% will endure such exposure throughout their lives,” warns Grant. “The same picture emerges for other climate extremes examined, though with slightly lower affected fractions of the population. Yet the same unfair generational differences in unprecedented exposure is observed.” Children in tropical countries will bear the worst burden under a 1.5 °C scenario. However, under high-emission scenarios, nearly all children worldwide face the prospect of living an unprecedented life (see Figure 2).

Climate vulnerability and social injustice

The study also highlights the social injustice of climate change and its impacts. Under current climate policies, the most socioeconomically vulnerable children born in 2020 will almost all (95%) endure unprecedented exposure to heatwaves in their lifetime, compared to 78% for the least vulnerable group. “Precisely the most vulnerable children experience the worst escalation of climate extremes. With limited resources and adaptation options, they face disproportionate risks,” says Thiery.

Urgent Need for Global Climate Action

Ahead of COP30 in Brazil, nations must submit updated climate commitments. Under current policies, global warming would reach around 2.7 °C this century. This study and the related Save The Children report emphasize the urgency of keeping global warming below 1.5 °C for the children of today and tomorrow.

Inger Ashing, CEO of Save the Children International, said: “Across the world, children are forced to bear the brunt of a crisis they are not responsible for. Dangerous heat that puts their health and learning at risk; cyclones that batter their homes and schools; creeping droughts that shrivel up crops and shrink what’s on their plates. Amid this daily drumbeat of disasters, children plead with us not to switch off. This new research shows there is still hope, but only if we act urgently and ambitiously to rapidly limit warming temperatures to 1.5 °C, and truly put children front and centre of our response to climate change.”

“With global emissions still rising and the planet only 0.2 °C away from the 1.5 °C threshold, world leaders must step up to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and lessen the climate burden on today’s youth,” concludes Thiery.

Journal Reference:

Grant, L., Vanderkelen, I., Gudmundsson, L. et al., ‘Global emergence of unprecedented lifetime exposure to climate extremes’, Nature 641, 374–379 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-08907-1

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Vrije Universiteit Brussel

Warming climate making fine particulate matter from wildfires more deadly and expensive

Scientists say human-caused climate change led to 15,000 additional deaths from wildfire air pollution in the continental United States during the 15-year period ending in 2020.

About 35% of the additional deaths attributed to climate change occurred in 2020, the year of the historic Labor Day fires in the Pacific Northwest as well as major blazes in California, Colorado and Arizona.

The study, led by an Oregon State University researcher and published in Communications Earth & Environment, is the first to quantify how many people are dying because a warming climate is causing fires to send increasing amounts of fine particulate matter into the air, especially in the West.

The scientists estimate that during the study period a total of 164,000 deaths resulted from wildfire PM2.5, particles with a diameter of 2.5 micrometers or smaller that can be inhaled deeply into the lungs and even enter the bloodstream. They determined that 15,000 of those deaths were attributable to climate change – meaning that absent climate change, the total would have been 149,000.

The average annual death rate from wildfire PM2.5 during the study period was 5.14 per 100,000 people; by comparison, that’s roughly double the annual U.S. death rate from tropical cyclones such as hurricanes

The research also found a $160 billion economic burden associated with those 15,000 extra wildfire PM2.5 deaths. Economic burden from mortality considers factors such as productivity losses, health care costs and a concept known as value of a statistical life that assigns a monetary value to reduction in mortality risk.

The study, which looked at mortality risk on a county-by-county basis, showed the economic burden was greatest in California, Oregon and Washington.

“Without efforts to address climate change, wildfires and associated fine particulate matter will continue to increase,” said Bev Law, professor emerita in the OSU College of Forestry and the study’s leader. “Projections of climate-driven wildfire PM2.5 across the continental U.S. point to at least a 50% increase in mortality from smoke by midcentury relative to the decade ending with 2020, with resulting annual damages of $244 billion.”

Using publicly available datasets, Law and collaborators looked at how much additional area burned and how many people died from climate-change related wildfire PM2.5 during the 2006-20 study period, integrating climate projections, climate-wildfire models, wildfire smoke models, and emission and health impact modeling.

The authors note that as climate change exacerbates wildfire risk, PM2.5 emissions from fires have surged to the point that wildfires now account for almost half of all PM2.5 across the United States and have negated air quality improvements in multiple regions. They also say that absent abrupt changes in climate trajectories, land management and population trends, the impacts of climate change on human health via wildfire smoke will escalate.

“Exposure to PM2.5 is a known cause of cardiovascular disease and is linked to the onset and worsening of respiratory illness,” Law said. “Ongoing trends of increasing wildfire severity track with climate projections and underscore how climate change manifestations like earlier snowmelt, intensified heat waves and drier air have already expanded forest fire extent and accelerated daily fire growth rates.”

Researchers at the University of California, Merced, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the Woodwell Climate Research Center and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center of Harvard Medical School also took part in the study.

Journal Reference:

Law, B.E., Abatzoglou, J.T., Schwalm, C.R. et al., ‘Anthropogenic climate change contributes to wildfire particulate matter and related mortality in the United States’, Communications Earth & Environment 6, 336 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-025-02314-0

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Oregon State University

In Reddit posts about climate change, just 1 in 25 links are to scientific sources – versus mass media and social media sources – evidencing the lack of science-based debate

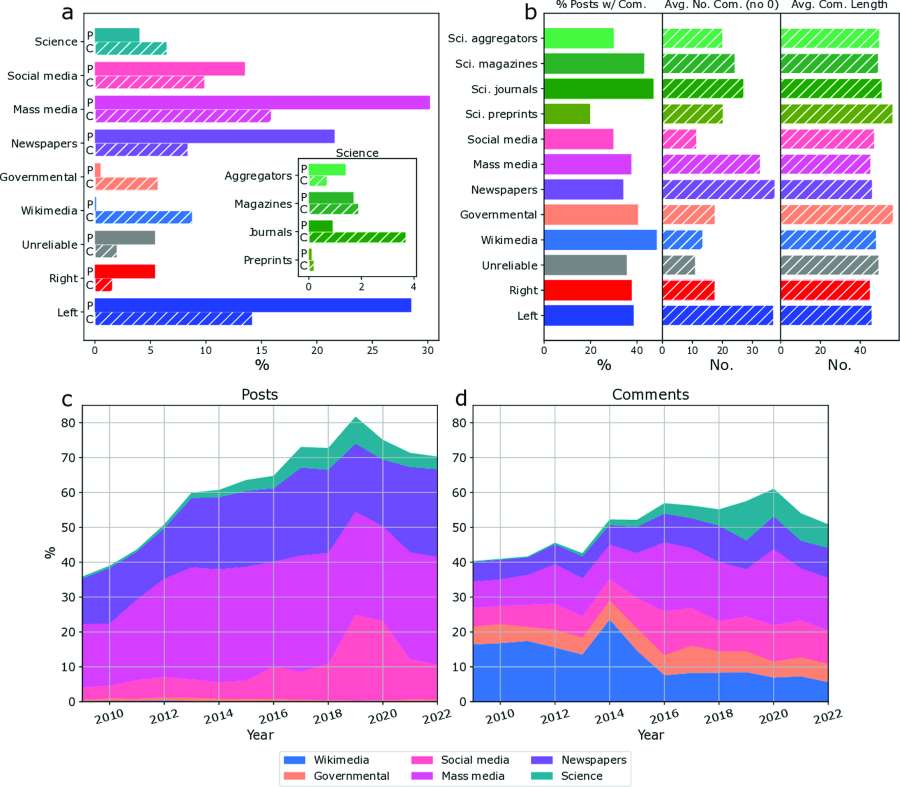

“Well-informed collective and individual action necessary to address climate change hinges on the public’s understanding of the relevant scientific findings. Social media has been a popular platform for the deliberation around climate change and the policies aimed at addressing it. Whether such deliberation is informed by scientific findings is an important step in gauging the public’s awareness of scientific resources and their latest findings.

“In this study, we examine the use of scientific sources in the course of 14 years of public deliberation around climate change on one of the largest social media platforms, Reddit. We find that only 4.0% of the links in the Reddit posts, and 6.5% in the comments, point to domains of scientific sources, although these rates have been increasing in the past decades.

“These links are dwarfed, however, by the citations of mass media, newspapers, and social media, the latter of which peaked especially during 2019–2020. Further, scientific sources are more likely to be posted by users who also post links to sources having central-left political leaning, and less so by those posting more polarized sources. Scientific sources are not often used in response to links to unreliable sources, instead, other such sources are likely to appear in their comments.

“This study provides the quantitative evidence of the dearth of scientific basis of the online public debate and puts it in the context of other, potentially unreliable, sources of information.” – Cornale et al. (2025) | Plos Climate

Journal Reference:

Cornale P, Tizzani M, Ciulla F, Kalimeri K, Omodei E, Paolotti D, et al., ‘The role of science in the climate change discussions on Reddit’, PLOS Climate 4 (5): e0000541 (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pclm.0000541

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by PLOS

Global study finds political left more trusting of climate scientists than right

A sweeping 26-country study reveals a consistent gap in trust toward climate scientists based on political ideology, with right-leaning individuals reporting lower trust than their left-leaning counterparts. The divide is especially stark in wealthier democracies and English-speaking nations, according to the research, published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology. The findings expand on past studies focused primarily on Western, English-speaking contexts.

“While climate scientists currently maintain fairly high levels of public trust — ranging from 58 percent in North America to 84 percent in South Asia — that trust is not held evenly across all groups,” says senior author Kai Ruggeri, PhD, professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. “The political divide in trust isn’t inevitable. In fact, the popularity of most climate policies is dramatically underrated, even across that divide. To have a better balance, we must engage all political perspectives and foster trust that transcends ideology.”

Trust in climate scientists is central to effective policies being implemented successfully because public support for climate policies is known to be linked to the level of trust in climate scientists. Furthermore, the links between fossil fuel emissions, warming temperatures, and how they are changing our climate, through frequent extreme weather events, as one example, often cannot be understood through direct experience.

Analyzing survey data from 10,641 participants across 26 nations, researchers found political ideology significantly influences trust in climate scientists — with a few exceptions. While right-leaning individuals showed lower trust in 22 countries, the pattern reversed in China and Indonesia, where left-leaning respondents were more skeptical. In Egypt and Georgia, political views made no difference, suggesting climate change remains less politicized in these regions. On average, participants identified as politically centrist.

Development, Democracy, and Emissions

The link between political views and distrust of climate scientists was strongest in wealthier, more democratic countries with high levels of greenhouse gas emissions. Researchers call this the “post-industrial paradox” — as nations develop, some people may see science as less essential to progress, making them more skeptical. In democracies, political divides can deepen this distrust. High-emitting countries also face well-funded misinformation campaigns, often from fossil fuel interests, that undermine trust in climate science.

Does Education Breed Distrust?

The researchers report some preliminary evidence that the link between political ideology and distrust of climate scientists may be slightly stronger among more educated individuals versus those with less education. While the difference is small, higher education may enable people to selectively interpret scientific information through an ideological lens—potentially deepening partisan divides on climate issues.

A Few Limitations

Participants were mostly young, and there was an over-representation of educated women compared to the general population, so the researchers say their findings might not apply to everyone. They also used simple yes/no-style questions about trust and political views, which can’t capture all the complexities of these topics. They note that it is important to distinguish between trusting climate science and trusting climate scientists, as people may feel differently about each. Future research could explore these nuances in more depth.

Implications for Communications

The study highlights the need for climate communication strategies that address ideological divides. To increase trust among right-leaning audiences, researchers recommend emphasizing climate change’s immediate impacts rather than distant future consequences and partnering with trusted local figures — from community leaders to political representatives — who can authentically convey scientific consensus. These approaches must be carefully adapted to national contexts, given how the politics of climate trust vary across borders.

“Failing to consider the perspectives of entire populations will inevitably create roadblocks for evidence-based policies. Closing this gap requires meeting people where they are, through messengers and messages that resonate across ideological lines,” says Ruggeri. “What is especially unique about this study is that it was led entirely by students and early career researchers, who took the initiative to make creative use of data on an extremely important topic.”

All team members were connected through the Junior Researcher Programme, which also partners with Columbia’s Global Behavioral Science Initiative.

Journal Reference:

Amanda Remsö, Justus Schmidt, Sandra J. Geiger, Bojana Većkalov, Živa Krajnc, Isobel Laughton, Mariam Shavgulidze, Emma A. Renström, Kai Ruggeri, ‘Trust in Climate Scientists is Associated with Political Ideology: A 26-Country Analysis’, Journal of Environmental Psychology online, 102609 (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2025.102609

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Mailman School of Public Health | Columbia University

Silent scorpion-sting epidemic in Brazil driven by urbanization and climate change (Interview)

Prof Eliane Candiani Arantes – heads the Laboratory of Animal Toxins at the School of Pharmaceutical Sciences of Ribeirao Preto, University of São Paulo (USP) where her group is working with toxins found in the venom of the Crotalus durissus terrificus rattlesnake and the Tityus serrulatus scorpion. They also study the venom of scorpions from the Amazon region, which are still not well understood.

Prof Manuela Berto Pucca – heads the Laboratory of Immunology and Toxinology at the School of Pharmaceutical Sciences at São Paulo State University (UNESP). Her research focuses on venomous animals, the molecular complexity of their venoms, and the development of next-generation antivenoms.

***

What inspired you to become a researcher?

Arantes: I have always enjoyed learning and sharing knowledge, and conducting research aligns perfectly with both of these activities. Studying venomous animals is exciting and dynamic, as it constantly presents new challenges and generates knowledge that can benefit many people.

Pucca: Between the ages of 12 and 15 I had a science teacher who didn’t just explain the natural world — she revealed its magic. Her classes felt like stepping into a secret universe, where every question had the power to open a door. That’s when I knew I didn’t just want to learn science — I wanted to live it. For me, science turns a simple ‘why?’ into something that can transform lives.

Can you tell us about the research you’re currently working on?

Arantes: In recent projects, my group focused on the expression of snake toxins with healing properties or effects on the coagulation system, as well as scorpion toxins with immunosuppressive effects. Additionally, we are working to improve the potential of these toxins as pharmaceutical drugs.

Pucca: At UNESP, within the Immunology and Toxinology Laboratory, we study a remarkable diversity of venomous species — including snakes, scorpions, spiders, and even certain types of frogs. These molecules — some of the most lethal in nature — can also become powerful tools for healing when studied deeply.

Are there any common misconceptions about this area of research? How would you address them?

Pucca: Yes, and one of the most widespread is the idea that venomous animals are our enemies. They’re not. These animals act defensively, not offensively. They’re part of the natural world and play essential ecological roles, from controlling pest populations to maintaining biodiversity. Another misconception is that envenomations are rare or only happen in the wild. In reality, in countries like Brazil, snakebites and scorpion stings are a significant public health issue which is often invisible in the broader public discourse.

Arantes: To challenge these misconceptions, we need to bring science closer to society — through education, dialogue, and respect for both scientific knowledge and traditional wisdom. Understanding that these animals are not threats, but part of the ecosystem we all share, is a crucial first step toward coexistence — and better public health.

What would you like people to know if they get stung by a scorpion?

Arantes: First: stay calm but act quickly. Arantes: First: stay calm but act quickly. If someone is stung, don’t wait for symptoms to worsen — go to the nearest healthcare facility immediately. In Brazil, the SUS provides treatment for scorpion stings free of charge, and antivenom (soro antiescorpiônico) is available at reference hospitals and emergency centers throughout the country. It’s most effective when administered early, especially in moderate to severe cases.

Pucca: At home, do not apply tourniquets, cut the wound, or try to suck out the venom. These outdated methods are ineffective and potentially harmful. Clean the area with soap and water, apply a cold compress for pain relief, and get to a hospital as soon as possible. Finally, prevention is key: Scorpions thrive in cluttered, humid environments. Keep areas clean, seal cracks in walls, use screens on drains, and always check shoes, towels, and clothes before using them.

Tackling the reasons for more stings is anything but easy, but are there any practical and feasible interventions?

Pucca: We need to start with the basics. I’ve been working in places where scorpion stings are a daily fear, especially in poor and crowded areas. People are living side by side with Tityus serrulatus, and most don’t even realize how quickly this species spreads. One scorpion alone can start a whole colony. But there are things we can do. Simple things — cleaning up debris, improving waste collection, sealing walls and drains.

Arantes: We also need more education. People need to know how to protect themselves, what symptoms to watch for, and where to go in case of a sting. Prevention is possible. We just need to take it seriously. We also need to strengthen our public health system, especially in rural and underserved areas.

What are some of the areas of research you’d like to see tackled in the years ahead?

Arantes: One of the most urgent needs is the modernization of antivenom production. Right now, most antivenoms are still made using a method that’s over a hundred years old — injecting venom into horses, then extracting and purifying antibodies from their blood. These serums can save lives, but they can also cause serious side effects and are difficult to distribute in remote or underserved areas.

Pucca: We urgently need to invest in next-generation antivenoms, especially fully human antibodies. These promise safer, more effective, and more accessible treatments. Beyond treatment, we’re also unlocking the therapeutic potential of venom itself. Nature has evolved these molecules over millions of years — we’re just beginning to understand how they can be turned into tools for healing, not just harm.

In your opinion, why is your research important?

Arantes: The research conducted by my team helps improve treatments for snake and scorpion envenomation, expands our understanding of molecules with promising therapeutic effects, and modifies these molecules to make them more suitable for therapeutic use.

Pucca: Our work goes far beyond the lab. In Brazil’s Amazon region, I’ve had the opportunity to collaborate directly with Indigenous communities, including the Yanomami people. Where healthcare access is limited, a venomous sting or bite can be fatal if treatment isn’t immediate and effective. That’s why we’re also focused on developing next-generation antivenoms — safer, more effective, and accessible to those who need them most. If we can help close that gap, then we are not only advancing knowledge, but honoring the lives of those who’ve been invisible for far too long.

How has open science benefited the reach and impact of your research?

Pucca: Open science has completely transformed the way my research connects with the world. By making our data, results, and publications openly accessible, we’ve been able to reach not just scientists — but also healthcare professionals, policymakers, and even directly affected communities.

Arantes: It’s helped amplify the visibility of neglected issues, especially in Brazil. Through open access, researchers from under-resourced institutions — who may not have access to paywalled journals — can collaborate, build on our work, and take action locally. That kind of impact matters.

Journal Reference:

Pucca MB, Cavalcante JS, Jati SR, Cerni FA, Ferreira RS Jr and Arantes EC, ‘Scorpions are taking over: the silent and escalating public health crisis in Brazil’, Frontiers in Public Health 13: 1573767 (2025). DOI: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1573767

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Frontiers

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay