Summary:

Meeting the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C target could preserve more than half of the world’s glacier mass, according to a new study published in Science. The international research team, led by Harry Zekollari, used eight glacier models to simulate the long-term evolution of more than 200,000 glaciers under different global temperature scenarios. Even if global temperatures stabilize at current levels, glaciers are projected to lose 39% of their mass compared to 2020 levels, contributing over four inches to sea-level rise. But the scale of future loss depends heavily on policy choices made today.

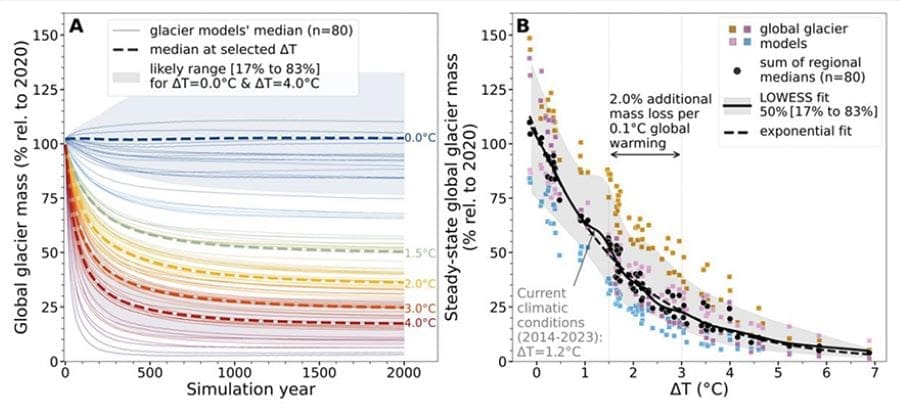

The models show that if global warming reaches 2.7°C by 2100, as projected under current policies, only 24% of today’s glacier mass would remain. In contrast, limiting warming to 1.5°C would preserve 53% of glacier mass, preventing much of the projected sea-level rise and its cascading effects on water supply, ecosystems, and coastal stability. “For each additional 0.1°C of warming, we stand to lose roughly another 2% of glacier ice,” said David Rounce, co-author and assistant professor at Carnegie Mellon University.

With glaciers adjusting slowly to temperature change, the study highlights the long-term implications of today’s emissions choices for future generations and global water systems.

Climate policy can save half of the world’s glaciers

Current climate policies put the world on track for a temperature increase of 2.7°C by the year 2100. The repercussions could be irreversible and far-reaching, which is why policymakers and scientists are racing to meet climate targets like the critical 1.5°C threshold proposed in the Paris Agreement.

The new study underscores what’s at stake for the world’s glaciers at these temperature levels. Examining more than 200,000 glaciers outside of the Greenland and Antarctic Ice Sheets, an international team of researchers used eight glacier models to simulate the evolution of the glaciers under various climate change scenarios. Results show that, because glaciers adjust slowly to temperature change, substantial mass loss is unavoidable even if temperatures stabilized today; however, strong climate policy can preserve twice as much ice compared to current warming trajectories.

In 2025, aptly named the International Year of Glacier Preservation by the United Nations, climate scientists estimate that global temperatures have already increased by 1.2°C over pre-industrial levels. Even without any further warming, the team projects that 39% of glaciers will disappear globally — enough melt to contribute more than four inches to sea-level rise. And the consequences grow with each fraction of a degree.

“For each additional 0.1°C of warming, we stand to lose roughly another 2% of glacier ice,” said David Rounce, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Carnegie Mellon University. Rounce, a co-author on the Science paper, recently presented these findings at the United Nations 2024 Climate Change Conference and 2025 World Day for Glaciers celebration.

As a result, if the world were to warm to 2.7°C, only 24% of present-day glacier mass would remain, contributing more than nine inches to sea-level rise. But, more than half of that loss could be prevented under the goals of the Paris Agreement; at a 1.5°C temperature increase, 53% of global glacier mass could be preserved, alleviating hazards like flooding, erosion, and freshwater deficiency in nearby and coastal communities.

“The glacier melt we’re seeing today reflects warming from decades ago,” said Rounce. “Decisions we make now will determine the future of our water, coastlines, and ecosystems around the world.”

***

This study is a key contribution to the United Nations International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation (2025), underlining the urgent need for global climate action to save the world’s glaciers. The research was conducted as part of the Glacier Model Intercomparison Project, coordinated by the Climate and Cryosphere Project of the World Climate Research Programme.

Journal Reference:

Harry Zekollari et al., ‘Glacier preservation doubled by limiting warming to 1.5°C versus 2.7°C’, Science 388, 6750, 979-983 (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adu4675

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Maya Westcott | College of Engineering | Carnegie Mellon University (CMU)

Featured image: The summit of Huayna Potosí, a mountain near La Paz, Bolivia. Here we find the Zongo glacier, one of several in the tropical Andes Mountains, that are now smaller than at any point since the end of the last ice age 11,700 years ago. Credit: Gabriel Ramos | Pexels