Summary:

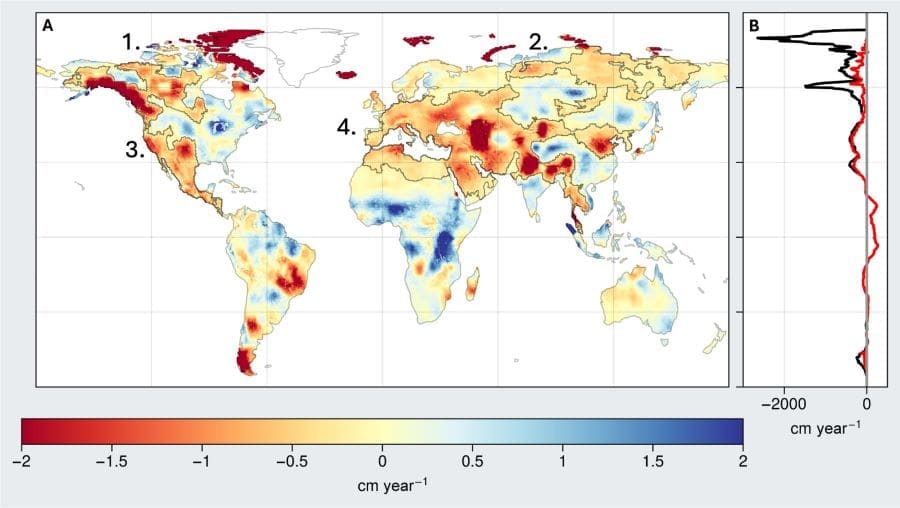

Freshwater is disappearing from the world’s continents at an alarming rate, according to a major international study published in Science Advances. Researchers analyzed more than two decades of satellite observations from NASA’s GRACE and GRACE-FO missions and found that Earth’s terrestrial water storage has declined significantly since 2002, largely due to extreme droughts, climate change, and overuse of groundwater. The study identified four massive “mega-drying” regions – in North and Central America, northern Canada and Alaska, northern Russia, and across the Middle East, North Africa, and Eurasia – where losses are now contributing more to sea level rise than melting glaciers and ice sheets.

The research shows that dry regions are expanding at a rate double the size of California every year, and they are drying faster than wet regions are becoming wetter. In total, 75% of the global population lives in countries that have been losing freshwater for the past 22 years. Groundwater accounts for 68% of the non-glacial freshwater loss on land. The findings point to a significant shift in global water balance with wide-reaching consequences for food production, water security, and sea level rise – signaling an urgent need for improved water management strategies worldwide.

New global study shows freshwater is disappearing at alarming rates

New findings from studying over two decades of satellite observations reveal that the Earth’s continents have experienced unprecedented freshwater loss since 2002, driven by climate change, unsustainable groundwater use and extreme droughts. The study, led by Arizona State University, highlights the emergence of four continental-scale “mega-drying” regions, all located in the northern hemisphere, and warns of severe consequences for water security, agriculture, sea level rise and global stability.

The research team reports that drying areas on land are expanding at a rate roughly twice the size of California every year. And, the rate at which dry areas are getting drier now outpaces the rate at which wet areas are getting wetter, reversing long-standing hydrological patterns.

The negative implications of this for available freshwater are staggering. 75% of the world’s population lives in 101 countries that have been losing freshwater for the past 22 years. According to the United Nations, the world’s population is expected to continue to grow for the next 50 to 60 years – at the same time the availability of freshwater is dramatically shrinking.

The researchers identified the type of water loss on land, and for the first time, found that 68% came from groundwater alone – contributing more to sea level rise than the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets combined.

“These findings send perhaps the most alarming message yet about the impact of climate change on our water resources,” said Jay Famiglietti, the study’s principal investigator and a Global Futures Professor with the ASU School of Sustainability. “Continents are drying, freshwater availability is shrinking, and sea level rise is accelerating. The consequences of continued groundwater overuse could undermine food and water security for billions of people around the world. This is an ‘all-hands-on-deck’ moment – we need immediate action on global water security.”

The researchers evaluated more than two decades of data from the US-German Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) and GRACE-Follow On (GRACE-FO) missions, looking at how and why terrestrial water storage has changed since 2002. Terrestrial water storage includes all of Earth’s surface and vegetation water, soil moisture, ice, snow, and groundwater stored on land.

“It is striking how much non-renewable water we are losing,” said Hrishikesh A. Chandanpurkar, lead author of the study and a research scientist for ASU. “Glaciers and deep groundwater are sort of ancient trust funds. Instead of using them only in times of need such as a prolonged drought, we are taking them for granted. Also, we are not trying to replenish the groundwater systems during wet years and thus edging towards an imminent freshwater bankruptcy.”

Tipping point and worsening continental drying

The study identified what seems to be a tipping point around 2014-15 during a time considered “mega El-Niño” years. Climate extremes began accelerating and in response, groundwater use increased and continental drying exceeded the rates of glacier and ice sheet melting.

Additionally, the study revealed a previously unreported oscillation where after 2014, drying regions flipped from being located mostly in the southern hemisphere to mostly in the north, and vice versa for wet regions.

One of the key drivers contributing to continental drying is the increasing extremes of drought in the mid-latitudes of the northern hemisphere, for example, in Europe. Additionally, in Canada and Russia, snow, ice, and permafrost melting increased over the last decade, and the continued depletion of groundwater globally is a major factor.

In a previous study, members of the team studied terrestrial water storage from satellite data spanning 2002 – 2016. In the new study, the team looked at more than 20 years of data and discovered a critical, major development in continental drying. Several regional drying patterns and previously identified localized ‘hotspots’ for terrestrial water storage loss are now interconnected – forming the four continental-scale mega drying regions.

These include:

- Southwestern North America and Central America: this region includes major food-producing regions across the American Southwest, along with major desert cities such as Phoenix, Tucson, Las Vegas, and major metropolitan areas such as Los Angeles and Mexico City.

- Alaska and Northern Canada: this region includes melting alpine glaciers in Alaska and British Columbia, snow and permafrost melting across the Canadian high latitudes, and drying in major agricultural regions such as British Columbia and Saskatchewan

- Northern Russia: this region is experiencing major snow and permafrost melting across the high latitudes

- Middle East-North Africa (MENA) Pan-Eurasia: this region includes major desert cities including Dubai, Casablanca, Cairo, Baghdad and Tehran; major food producing regions including Ukraine, northwest India, and China’s North China Plain region; the shrinking Caspian and Aral Seas; and major cities such as Barcelona, Paris, Berlin, Dhaka and Beijing.

In fact, the study showed that since 2002, only the tropics have continued to get wetter on average by latitude, something not predicted by IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) climate models – sophisticated computer programs used to project future climate scenarios. Continuous records are critical in understanding the long-term changes in the water cycle.

“This study really shows how important it is to have continuous observations of a variable such as terrestrial water storage,” said Chandanpurkar. “GRACE records are really getting to the length where we are able to robustly see long-term trends from climate variability. More in-situ observations and data sharing would further support in making this separation and inform water management.”

A Planetary Wake-Up Call

The unprecedented scale of continental drying threatens agriculture and food security, biodiversity, freshwater supplies and global stability. The current study highlights the need for ongoing research at scale to inform policymakers and communities about worsening water challenges and opportunities to create meaningful change.

“This research matters. It clearly shows that we urgently need new policies and groundwater management strategies on a global scale,” said Famiglietti, who is also with the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory and a former Senior Water Scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “While efforts to mitigate climate change are facing challenges, we can address continental drying by implementing new policies around regional and international groundwater sustainability. In turn, this will slow the rate of sea level rise and help preserve water for future generations.”

The study calls for immediate action to slow and reverse groundwater depletion, protect remaining freshwater resources, and adapt to the growing risk of water scarcity and coastal flooding. The research team goes on to say that strategic water management, international cooperation, and sustainable policies are essential to preserving water for future generations and mitigating further damage to planetary systems.

The research will also support an upcoming World Bank Group flagship report that will delve deeper into these findings, including the human and economic implications of continental drying, and present actionable solutions for countries to address the growing freshwater crisis.

About the Study

The findings are based on over 22 years of terrestrial water storage data from US-German GRACE and GRACE-FO satellite missions. The full report details the scientific analyses and regional breakdowns of the drying trends, which have proven robust and persistent despite climate variability.

The research team includes scientists from Arizona State University; Hrishikesh A. Chandanpurkar, FLAME University; John T. Reager and David N. Wiese, JPL; Kaushik Gopalan and Yoshihide Wada, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology; Kauru Kakinuma, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology; and Fan Zhang, The World Bank.

***

This research was funded by the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory at Arizona State University, the GRACE Follow-On Science Team, and World Bank Global Water Monitoring.

Journal Reference:

Hrishikesh A. Chandanpurkar, James S. Famiglietti, Kaushik Gopalan et al.,‘Unprecedented continental drying, shrinking freshwater availability, and increasing land contributions to sea level rise’, Science Advances 11, 30: eadx0298 (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adx0298

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Sandy Keaton Leander | Arizona State University (ASU)

Featured image credit: Sophia Franz