Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press daily roundup (August 11, 2025), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

Connecting biodiversity with public health outcomes

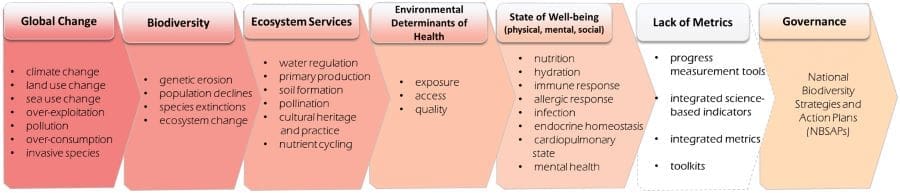

An international team of scientists from the GLOBE Institute’s Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate at the University of Copenhagen, the Centre for Climate Change and Planetary Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and the Inter-American Institute for Global Change Research based in Panama is urging governments to adopt a new generation of indicators that directly connect environmental changes to public health outcomes.

A new paper argues that the health of ecosystems and the health of people are deeply intertwined – but most policies still treat them as separate issues.

Published in PLOS Global Public Health, the study highlights how two major international agreements – the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and the Global Action Plan on Biodiversity and Health – offer a timely opportunity to integrate public health considerations into environmental planning, and vice versa.

Ecosystems provide critical services: clean water, food, disease control, climate regulation, and mental well-being. And as global biodiversity continues to decline, the risks to human health are rising. The paper warns that without integrated metrics – measures that assess how environmental change impacts health – governments lack the tools to respond effectively.

The authors review several scientific approaches – including conservation biology, Indigenous worldviews, One Health, and planetary health – that all aim to connect ecological and human health. They call for collaboration across these communities to develop integrated metrics that are scientifically grounded, scalable, and relevant to policy.

They also emphasize that such indicators must reflect the complexity of both ecosystems and health, while remaining practical for governments to use in national planning and reporting.

As countries revise their biodiversity strategies in line with new international agreements, the authors urge policymakers to include public health metrics. Doing so could help align investments, inform risk assessments, and ensure that efforts to protect nature also support human well-being.

“This is about making better decisions with the best available knowledge,” says author Dr. Sarah Whitmee. “We can’t afford to ignore the links between a healthy environment and a healthy population.”

Author Liz Willetts adds: “Governments have repeatedly asked for these kinds of indicators, but progress has been slow. Our paper outlines what’s needed to move forward.”

Author Professor David Nogués-Bravo summarizes: “Biodiversity loss is not just about nature – it’s about people’s well-being. To protect both, we need shared tools that can show us how the health of our environment affects our own.”

***

(Adapted from release text courtesy of the University of Copenhagen.)

Journal Reference:

Nogués-Bravo D, Whitmee S, Willetts L, ‘Metrics for biodiversity and health policy integration’, PLOS Global Public Health 5 (7): e0004624 (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0004624

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by PLOS

We might inhale 68,000 lung-penetrating microplastics daily in our homes and cars

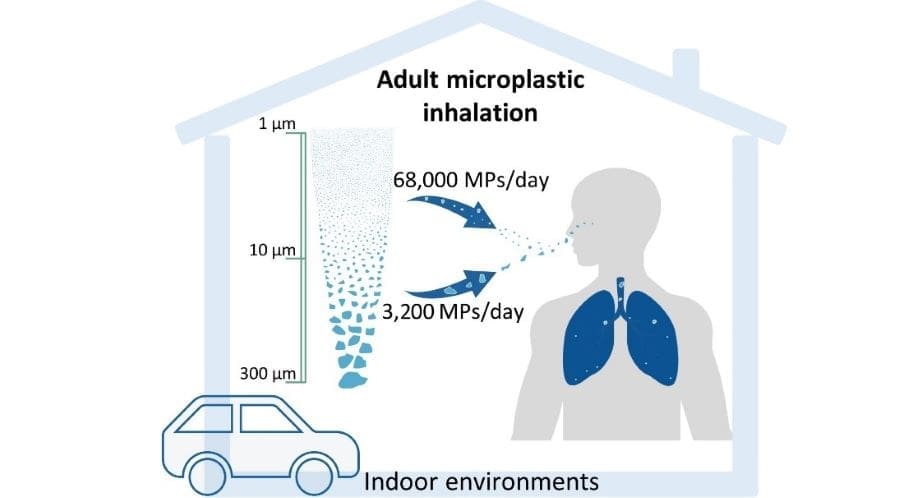

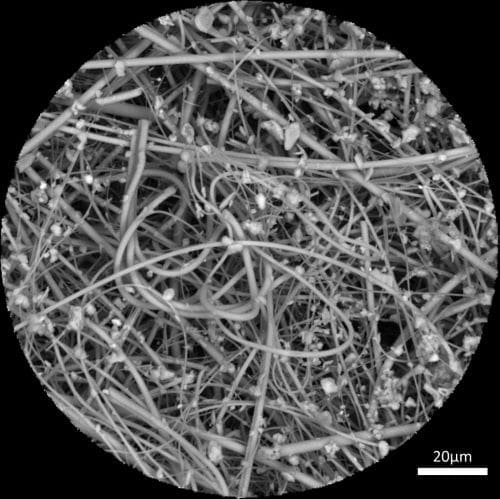

New measurements of fine microplastic particles suspended in the air in homes and cars suggest that humans may be inhaling far greater amounts of lung-penetrating microplastics than previously thought. Nadiia Yakovenko and colleagues at the Université de Toulouse, France, present these findings in the open-access journal PLOS One.

Prior research has detected tiny fragments of plastic known as microplastics suspended in the air across a wide variety of outdoor and indoor environments worldwide. The ubiquity of these airborne pollutants has raised concerns about their potential health effects, as small-sized inhaled microplastic particles may penetrate the lungs and could pose risks of oxidative stress, immune-system effects, and organ damage.

However, prior research on airborne microplastics has mostly focused on larger particles ranging from 20 to 200 micrometers in diameter, which are less likely to penetrate the lungs than particles of 10 micrometers across or less.

To help improve understanding of the risk of microplastic inhalation, Yakovenko and colleagues collected air samples from their own apartments, as well as from their own cars in realistic driving conditions. A technique called Raman spectroscopy enabled them to measure concentrations of microplastics, including those from 1 to 10 micrometers across, in 16 air samples.

They found that the median concentration of detected microplastics in the apartment air samples was 528 particles per cubic meter, and in the cars, 2,238 particles per cubic meter. Ninety-four percent of the detected particles were smaller than 10 micrometers. (While car levels were higher than apartment levels, the difference was not statistically significant because of high variability of microplastic concentration in both environments.)

The researchers then combined their results with previously published data on exposure to indoor microplastics, estimating that adults inhale about 3,200 microplastic particles per day in the range of 10 to 300 micrometers across, and 68,000 particles of 1 to 10 micrometers per day – 100 times more than prior estimates for small-diameter exposures.

These findings suggest that health risks due to inhalation of lung-penetrating microplastics may be higher than previously thought. Further research will be needed to confirm and expand on these results.

The authors add: “We found that over 90% of the microplastic particles in indoor air across both homes and cars were smaller than 10 µm, small enough to be inhaled deep into the lungs. This was also the first study to measure microplastics in the car cabin environment, and overall, we detected indoor concentrations up to 100 times higher than previous extrapolated estimates, revealing indoor air as a major and previously underestimated exposure route of fine particulate microplastic inhalation.”

“Everywhere we look, we find microplastics, even in the air we breathe inside our homes and cars. The biggest concern is how small these particles are completely invisible to the naked eye. We inhale thousands of them every day without even realizing it. Deep inside our lungs, microplastics release toxic additives that reach our blood and cause multiple diseases.”

Journal Reference:

Yakovenko N, Pérez-Serrano L, Segur T, Hagelskjaer O, Margenat H, Le Roux G, et al., ‘Human exposure to PM10 microplastics in indoor air’, PLoS One 20 (7): e0328011 (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0328011

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by PLOS

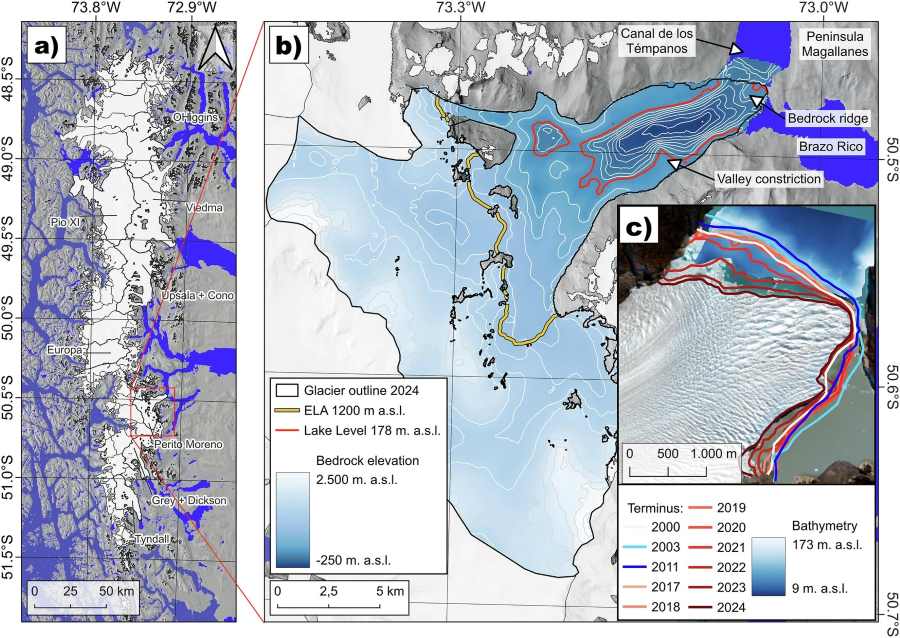

Perito Moreno Glacier retreat has recently accelerated substantially

The Perito Moreno Glacier in Argentina – often described as one of the most stable glaciers in Patagonia – is retreating far more rapidly than previously thought, according to a paper in Communications Earth & Environment. The results show that, over the last few years, the glacier has retreated by as much as 800 metres in some areas, and that it may collapse and retreat by several kilometres in the near future.

The Perito Moreno Glacier is a 30-kilometre-long glacier in the Argentine Patagonia, fed by the Southern Patagonian Ice Field in the Andes and terminating in Lago Argentino. Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1981, it is one of the most famous glaciers in the world and is a major Argentinian tourist destination due to its size and accessibility. Unlike most glaciers fed by the Patagonian Ice Fields, Perito Moreno remained relatively stable between 2000 and 2019, retreating by less than 100 metres over the period. However, there has been a substantial increase in the rate of retreat since 2019 – but scientists are unsure why.

Moritz Koch and colleagues used radar to survey the thickness of the glacier’s ice during two helicopter flights in March 2022. They then mapped the lakebed beyond the glacier’s terminus, and combined these surveys with satellite data to investigate changes in the glacier’s surface height and surface velocity between 2000 and 2024. The authors found that in recent years there has been a more than sixteen-fold increase in the thinning rate of the glacier at the terminus, from 0.34 metres per year between 2000 and 2019 to an average of 5.5 metres per year between 2019 and 2024. In addition, in some areas the glacier had retreated by more than 800 metres since 2019.

The surveys also revealed the presence of a large ridge beneath the glacier’s terminus – which the glacier is currently grounded on – that may have been responsible for its pre-2019 stability. The authors caution that if the glacier’s current thinning rate persists, it will detach from the ridge and rapidly retreat for several kilometres, as the increased water depth below the glacier upstream of the ridge will lead to an increased rate of iceberg calving. However, it is not yet clear when this might happen.

Journal Reference:

Koch, M., Sommer, C., Blindow, N. et al., ‘The state and fate of Glaciar Perito Moreno Patagonia’, Communications Earth & Environment 6, 572 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-025-02515-7

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Springer Nature

Liming can help enhance carbon capture in agricultural fields

Adding crushed calcium carbonate – limestone – to agricultural fields can remove tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere each year while improving crop yields, a Yale-led study published in Nature Water found.

Greenhouse gases in the atmosphere hit a record high in 2024 reaching over 420 parts per million. The U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has identified carbon removal as one key tool in limiting warming to 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels to help mitigate climate change. To reach that target, 15 billion tons of carbon would have to be removed from the atmosphere each year.

“There is growing scientific consensus that removing carbon from the atmosphere is necessary to hit carbon goals. At this point, halting emissions won’t be enough,” Peter Raymond, the Oastler Professor of Biogeochemistry at the Yale School of the Environment and co-director of the Yale Center for Natural Carbon Capture (YCNCC), said.

Raymond worked with a team of scientists on a perspective of applying crushed calcium carbonate to farmlands, a natural carbon removal process. They found that limestone can support farm productivity while increasing carbon capture.

Calcium carbonate is commonly sourced from limestone formed by the fossilized remains of marine life. While it is often applied to farmland to feed growing plants and balance the effects of nitrogen fertilizers that lower soil pH, its potential for storing carbon also makes it a valuable tool in fighting climate change, Raymond said.

When bicarbonate formed from limestone’s interaction with soils washes from fields into rivers and oceans, it has the potential to store carbon for millennia, he said.

Study coauthor Noah Planavsky, associate professor of earth and planetary science at Yale, and member of the scientific leadership team of YCNCC, said applying multiple tons of limestone per acre could potentially remove billions of tons of carbon dioxide before the end of the century. He added that limestone amendments could be used in conjunction with other soil amendments, including silicate rocks and organic amendments, to turn farmlands from being a major carbon source into being a carbon sink.

Agriculture is one of the largest greenhouse gas emitting sectors. Lime, which can react with nitrogen fertilizer and release carbon, has been listed as a carbon source by the IPCC. However, the researchers said that the acid from nitrogen fertilizer is the actual problem and, in most cases, adding enough limestone to improve soil levels will lead to CO₂ removal over time.

Liming has additional benefits as well, the authors noted. Bicarbonate from agricultural liming that washes into oceans can raise ocean pH and support shell building.

“To me, ocean acidification is just as important of a problem as atmospheric CO₂ levels,” said Raymond. “Other carbon dioxide removal mechanisms don’t always address oceans, but liming does. But first and foremost, modifying liming practices is a way to drive carbon removals that helps farmers. It should be a priority.”

Journal Reference:

Raymond, P., Planavsky, N. & Reinhard, C.T., ‘Using carbonates for carbon removal’, Nature Water (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s44221-025-00473-0

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Jen DeMoss | Yale University

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay