Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press roundup (January 6, 2026), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

— Press Release —

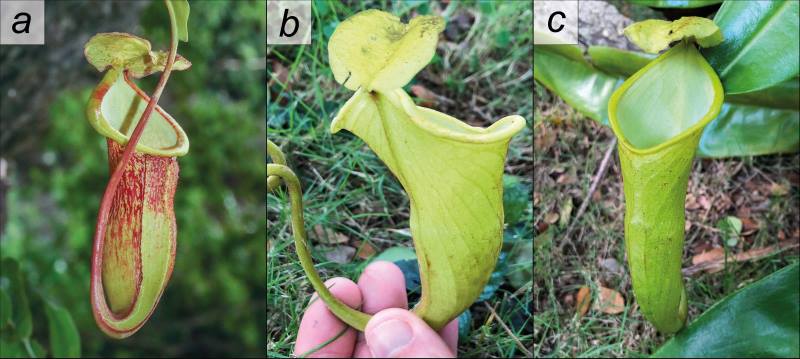

Newly discovered Philippine pitcher plant already in danger from climate change, poaching

Philippine scientists and an Australian expert have just confirmed a new species of pitcher plant found only on Palawan Island, but warn that it is already at risk of extinction due to frequent severe weather conditions and human encroachment.

A carnivorous vine that uses cup-shaped pitchers to trap insects, Nepenthes megastoma – from the Greek for “large mouth” – is found in only three locations in the steep and rocky karst terrain of the Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park.

“It’s amazing that these plants have evolved to survive in such difficult and inaccessible conditions. And yet, despite their hardiness, their existence is threatened by human activity – directly by way of encroachment and poaching, and indirectly through the effects of anthropogenic climate change,” said researcher John Charles Altomonte.

Well adapted to steep cliffs

The few areas where N. megastoma grows are so difficult to reach that the plant could only be properly documented using drones and long-range cameras. Ecologists first spotted them in 2013, but initially thought they were an already known species from nearby Borneo, N. campanulata. Only after detailed fieldwork, drone surveys, and close study were the researchers able to confirm the plant to be a previously unknown Philippine species.

N. megastoma is well adapted to surviving on steep cliff sides, with upward-pointing female flowers that facilitate vertical pollination and a fuzzy coating that helps collect rainwater. The shape of the plant’s pitchers also seems to differ based on the seasons, transitioning between a wider, flared form and a slimmer, elongated form – an adaptation that may help with water retention, according to the researchers.

Precarious survival, dwindling numbers

Yet despite these remarkable adaptations, the researchers estimate that there are only some 19 mature clumps with about 12 non-flowering plants, making the species’ survival highly precarious. They warn that this already extremely limited population is highly vulnerable to threats like typhoons, drought, poaching, and deforestation in surrounding areas due to human activities and settlements.

With fewer than 50 individual mature specimens known, the plant is classified as Critically Endangered per International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) guidelines. This number is likely to decline even further, owing to “increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events, particularly droughts and typhoons, as well as poaching,” the scientists warn in their paper. Illegally harvested specimens are already being sold in Metro Manila.

The imminent danger to N. megastoma’s survival despite its ability to adapt to a harsh cliffside environment underscores both the richness and fragility of Philippine biodiversity.

Journal Reference:

Altomonte, J.C.A., Collantes, J.P.R., Mangussad, V., Bustamante, R.A.A. & Robinson, A.S., ‘Nepenthes megastoma (Nepenthaceae), a micro-endemic pitcher plant from Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park, Palawan, Philippines’, Phytotaxa 728 (2): 93–107 (2025). DOI: 10.11646/phytotaxa.728.2.1

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Danika Geronimo | Ateneo de Manila University

— Press Release —

An AI-based blueprint for designing catalysts across materials

Hydrogen peroxide is widely used in everyday life, from disinfectants and medical sterilization to environmental cleanup and manufacturing. Despite its importance, most hydrogen peroxide is still produced using large-scale industrial processes that require significant energy. Researchers are thus seeking cleaner alternatives.

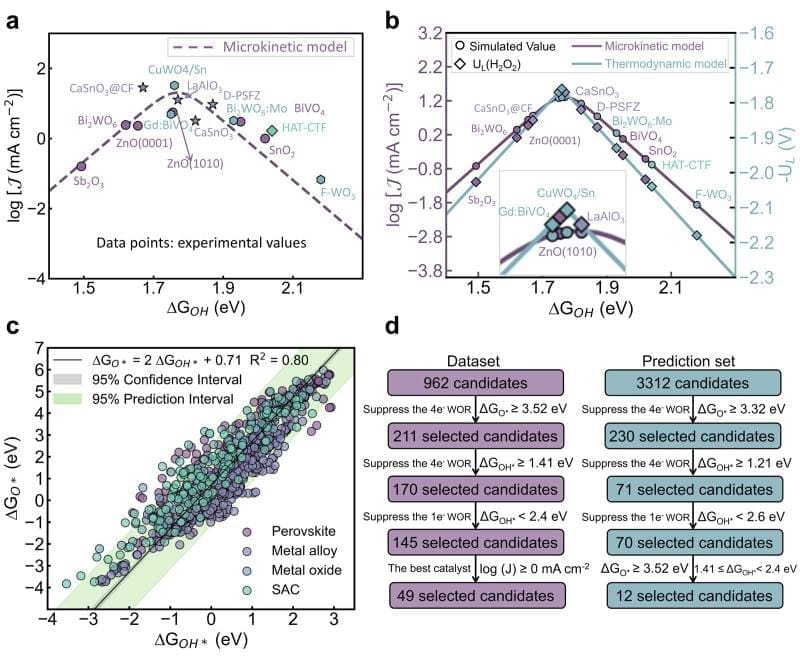

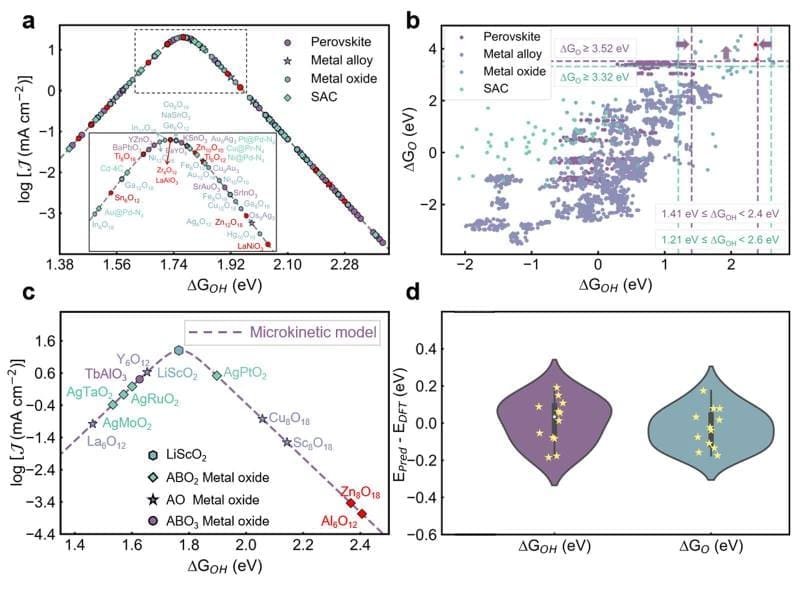

A team of researchers has made a breakthrough in this regard, developing a new computational framework that helps identify effective catalysts for producing hydrogen peroxide directly from water and electricity. The work focuses on the two-electron water oxidation reaction, an electrochemical process that can generate hydrogen peroxide in a more localized and potentially sustainable way.

This was no walk in the park, as Hao Li, the lead-author of the research, outlines. “Designing catalysts for this reaction has been difficult because catalysts come in many forms, such as metal alloys, metal oxides, and single-atom materials. Each type has different atomic structures, making it challenging to compare or predict their performance using a single method.”

To address this problem, Li and his team developed a new way to describe catalytic active sites at the atomic level. This approach, called a weighted atom-centered symmetry function, captures both the geometric arrangement of atoms and their chemical identities in a unified format. These descriptors were combined with machine learning models and reaction modeling to predict how well different materials would perform.

Using this framework, the team successfully predicted key reaction properties across a wide range of catalyst types. The predictions closely matched results from detailed quantum-mechanical calculations and previously reported experimental data, showing that the approach can work across diverse materials.

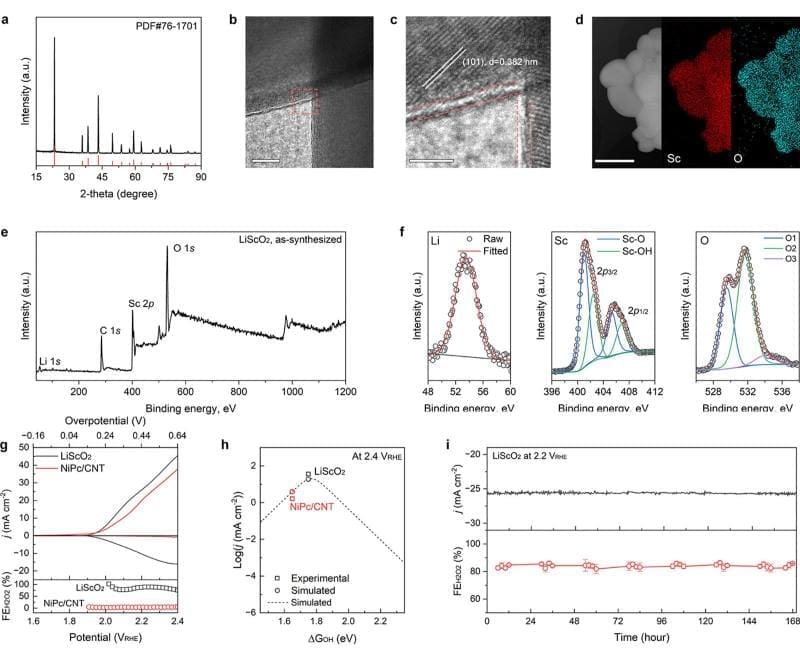

The researchers then used the model to rapidly screen potential catalysts and identified lithium scandium oxide (LiScO₂) as a promising candidate. Experiments confirmed that this material can produce hydrogen peroxide with about 90% efficiency and remain stable for nearly one week of continuous operation.

“This framework allows us to connect atomic-scale information directly to measurable performance,” adds Li. “It helps reduce trial-and-error in catalyst development and makes the search process more systematic.”

The framework has been implemented in the Digital Catalysis Platform (the largest experimental + computational catalysis database to date with digital platform for users, developed by the Hao Li Lab), where it can be used to predict reaction properties efficiently. Because the method treats different material classes in a consistent way, it can be extended beyond hydrogen peroxide production.

The researchers expect that this approach will support the design of catalysts for other important electrochemical reactions, contributing to cleaner chemical production and energy technologies in the future.

Journal Reference:

Z. Liu, Y. Liu, Y. Zhang, Y. Deng, Z. Zheng, R. Knibbe, T. Gao, M. Li, Z. Wang, B. Zhang, X. Jia, Di Zhang, H. Liu, X. Shao, Z. Gao, Li Wei, H. Li, W. Yang, ‘Universal Catalyst Design Framework for Electrochemical Hydrogen Peroxide Synthesis Facilitated by Local Atomic Environment Descriptors’, Angewandte Chemie International Edition online ver. e18027 (2025). DOI: 10.1002/anie.202518027

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Advanced Institute for Materials Research (WPI-AIMR) | Tohoku University

— Press Release —

Scientists sound alarm on erosion of long-term environmental data

A new Special Report published in the journal BioScience warns that long-term ecological and evolutionary research faces severe threats from lack of recurring funding and governmental/institutional support, to data manipulation and political interference, even as these studies become more crucial for addressing issues of broad societal importance, such as biodiversity loss and climate change.

Led by Vincent A. Viblanc of CNRS Écologie & Environnement in France, the report documents how “in early 2025, several leading environmental datasets maintained by national agencies in countries recently marked by electoral shifts were abruptly taken offline or replaced with curated versions that obscure or distort previously accessible information.”

The authors argue that “now more than ever, as manipulated facts and societal distrust in science are increasingly guiding mis- and disinformed politics, governmental programs are urgently needed to support data collection, establish data-grounded facts, inform political spheres, and refuel trust with society at large.”

The report highlights the CNRS SEE-Life program as a flagship model for institutional commitment to long-term science. Through sustained recurrent funding, SEE-Life support 79 long-term ecological studies across 28 French research centers and a network of over 100 international partners. Together more than 500 species across all major biomes are monitored, generating exceptional longitudinal datasets spanning 10 to 100 years, with unique longitudinal data ranging from 10 to 100 years of data.

To date, the program has produced over 3,000 publications and trained over 4,900 scientists, including more than 800 PhD students and postdoctoral fellows, constituting one of the most comprehensive long term biodiversity data sets worldwide.

The authors emphasize the enormous economic stakes, noting that healthy ecosystems provide services “estimated at some US$125 trillion per year,” while biological invasions alone cost “US$1,288 trillion in 2017 value over 1970–2017.”

The authors warn that “when long-term data becomes a target, our ability to understand – and respond to – global environmental change is profoundly compromised.”

Journal Reference:

Vincent A Viblanc, Élise Huchard, Gilles Pinay, Elena Ormeño, Céline Teplitsky, François Criscuolo, Dominique Joly, David Renault, Cécile Callou, Françoise Gourmelon, Sandrine Anquetin, Bénédicte Augeard, Fabienne Aujard, Sophie Ayrault, Philippe Grandcolas, Agathe Euzen, Agnès Mignot, Stéphane Blanc, ‘Science at Risk: The Urgent Need for Institutional Support of Long-Term Ecological and Evolutionary Research in an Era of Data Manipulation and Disinformation’, BioScience online ver., biaf175 (2026). DOI: 10.1093/biosci/biaf175

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by American Institute of Biological Sciences (AIBS)

— Press Release —

New research may help scientists predict when a humid heatwave will break

A long stretch of humid heat followed by intense thunderstorms is a weather pattern historically seen mostly in and around the tropics. But climate change is making humid heatwaves and extreme storms more common in traditionally temperate midlatitude regions such as the midwestern U.S., which has seen episodes of unusually high heat and humidity in recent summers.

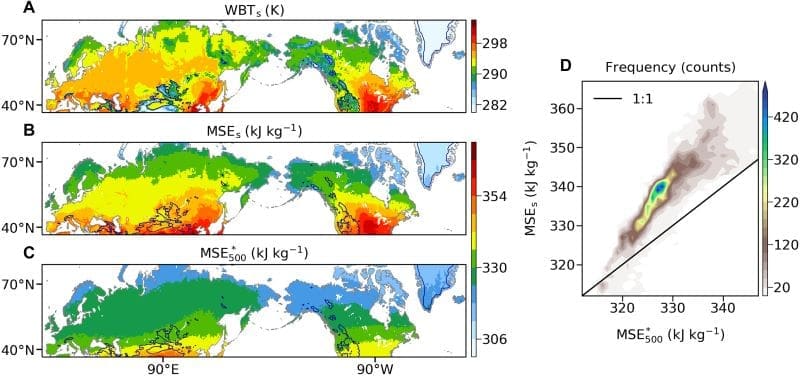

Now, MIT scientists have identified a key condition in the atmosphere that determines how hot and humid a midlatitude region can get, and how intense related storms can become. The results may help climate scientists gauge a region’s risk for humid heatwaves and extreme storms as the world continues to warm.

In a study appearing this week in the journal Science Advances, the MIT team reports that a region’s maximum humid heat and storm intensity are limited by the strength of an “atmospheric inversion” – a weather condition in which a layer of warm air settles over cooler air.

Inversions are known to act as an atmospheric blanket that traps pollutants at ground level. Now, the MIT researchers have found atmospheric inversions also trap and build up heat and moisture at the surface, particularly in midlatitude regions. The more persistent an inversion, the more heat and humidity a region can accumulate at the surface, which can lead to more oppressive, longer-lasting humid heatwaves.

And, when an inversion eventually weakens, the accumulated heat energy is released as convection, which can whip up the hot and humid air into intense thunderstorms and heavy rainfall.

The team says this effect is especially relevant for midlatitude regions, where atmospheric inversions are common. In the U.S., regions to the east of the Rocky Mountains often experience inversions of this kind, with relatively warm air aloft sitting over cooler air near the surface.

As climate change further warms the atmosphere in general, the team suspects that inversions may become more persistent and harder to break. This could mean more frequent humid heatwaves and more intense storms for places that are not accustomed to such extreme weather.

“Our analysis shows that the eastern and midwestern regions of U.S. and the eastern Asian regions may be new hotspots for humid heat in the future climate,” says study author Funing Li, a postdoc in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS).

“As the climate warms, theoretically the atmosphere will be able to hold more moisture,” adds co-author and EAPS Assistant Professor Talia Tamarin-Brodsky. “Which is why new regions in the midlatitudes could experience moist heatwaves that will cause stress that they weren’t used to before.”

Air energetics

The atmosphere’s layers generally get colder with altitude. In these typical conditions, when a heatwave comes through a region, it warms the air at ground level. Since warm air is lighter than cold air, it will eventually rise, like a hot air balloon, prompting colder air to sink. This rise and fall of air sets off convection, like bubbles in boiling water. When warm air hits colder altitudes, it condenses into droplets that rain out, typically as a thunderstorm, that can often relieve a heatwave.

For their new study, Li and Tamarin-Brodsky wondered: What would it take to get air at the surface to convect and ultimately end a heatwave? Put another way: What sets the limit to how hot a region can get before air begins to convect to eventually rain?

The team treated the question as a problem of energy. Heat is energy that can be thought of in two forms: the energy that comes from dry heat (i.e., temperature), and the energy that comes from latent, or moist, heat. The scientists reasoned that, for a given portion or “parcel” of air, there is some amount of moisture that, when condensed, contributes to that air parcel’s total energy. Depending on how much energy an air parcel has, it could start to convect, rise up, and eventually rain out.

“Imagine putting a balloon around a parcel of air and asking, will it stay in the same place, will it go up, or will it sink?” Tamarin-Brodsky says. “It’s not just about warm air that’s lifting. You also have to think about the moisture that’s there. So we consider the energetics of an air parcel while taking into account the moisture in that air. Then we can find the maximum ‘moist energy’ that can accumulate near the surface before the air becomes unstable and convects.”

Heat barrier

As they worked through their analysis, the researchers found that the maximum amount of moist energy, or the highest level of heat and humidity that the air can hold, is set by the presence and strength of an atmospheric inversion. In cases where atmospheric layers are inverted (when a layer of warm or light air settles over colder or heavier, ground-level air), the air has to accumulate more heat and moisture in order for an air parcel to build up enough energy to lift up and break through the inversion layer. The more persistent the inversion is, the hotter and more humid air must get before it can rise up and convect.

Their analysis suggests that an atmospheric inversion can increase a region’s capacity to hold heat and humidity. How high this heat and humidity can get depends on how stable the inversion is. If a blanket of warm air parks over a region without moving, it allows more humid heat to build up, versus if the blanket is quickly removed. When the air eventually convects, the accumulated heat and moisture will generate stronger, more intense storms.

“This increasing inversion has two effects: more severe humid heatwaves, and less frequent but more extreme convective storms,” Tamarin-Brodsky says.

Inversions in the atmosphere form in various ways. At night, the surface that warmed during the day cools by radiating heat to space, making the air in contact with it cooler and denser than the air above. This creates a shallow layer in which temperature increases with height, called a nocturnal inversion. Inversions can also form when a shallow layer of cool marine air moves inland from the ocean and slides beneath warmer air over the land, leaving cool air near the surface and warmer air above. In some cases, persistent inversions can form when air heated over sun-warmed mountains is carried over colder low-lying regions, so that a warm layer aloft caps cooler air near the ground.

“The Great Plains and the Midwest have had many inversions historically due to the Rocky Mountains,” Li says. “The mountains act as an efficient elevated heat source, and westerly winds carry this relatively warm air downstream into the central and midwestern U.S., where it can help create a persistent temperature inversion that caps colder air near the surface.”

“In a future climate for the Midwest, they may experience both more severe thunderstorms and more extreme humid heatwaves,” Tamarin-Brodsky says. “Our theory gives an understanding of the limit for humid heat and severe convection for these communities that will be future heatwave and thunderstorm hotspots.”

***

This research is part of the MIT Climate Grand Challenge on Weather and Climate Extremes. Support was provided by Schmidt Sciences.

Journal Reference:

Funing Li, Talia Tamarin-Brodsky, ‘Atmospheric stability sets maximum moist heat and convection in the midlatitudes’, Science Advances 12, eaea8453 (2026). DOI:10.1126/sciadv.aea8453

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Jennifer Chu | MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

Featured image credit: Freepik (AI Gen.)