Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press roundup (January 9, 2026), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

— Press Release —

How to make communities more resilient to climate change

The “compounded resilience” strategy lays out how local governments can take advantage of opportunities to both limit adverse impacts of climate change on their communities and reduce the greenhouse gas emissions that drive climate change.

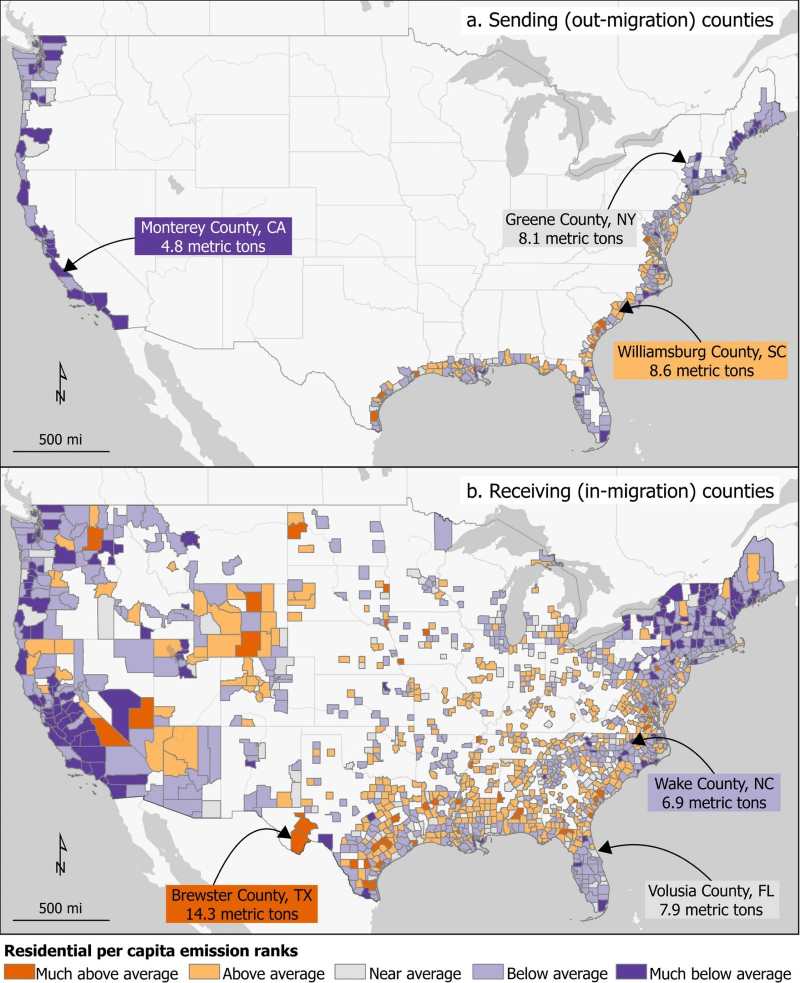

“Local governments are already dealing with the impacts of climate change,” says Christopher Galik, corresponding author of a paper – published in Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change – introducing the strategy, and a professor of public administration at North Carolina State University. “There are more extreme weather events, such as hurricanes and flooding, which force municipalities to make decisions about how, where and – in some cases – whether to rebuild. The changing climate is also influencing where people want to live, forcing some municipalities to make decisions about how and where new development will take place to accommodate a growing population.”

“All of these development and redevelopment decisions represent an opportunity for local governments to adopt policies that better prepare infrastructure and neighborhoods for the new conditions driven by climate change,” says Georgina Sanchez, co-author of the paper and director of research engagement in NC State’s Center for Geospatial Analytics. “Policies designed to incentivize adaptation strategies that make communities more resilient to flooding or other increasing challenges can be intentionally linked with efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate climate change itself. This combined approach is what we call ‘compound resilience.’”

“Instituting new policies and regulations that govern zoning, construction requirements, and so on, can be expensive and politically challenging,” Sanchez says. “But if communities are already having to build or rebuild in response to climate change, implementing compound resilience policies may be more feasible.”

“We are already seeing municipalities compete to attract people and businesses displaced by climate change, so there is an incentive for local governments to present themselves as being safe places for people to move and invest,” Galik says. “On the other hand, we find that, if nothing else changes, climate-driven shifts in where people live could actually increase greenhouse gas emissions. The argument we are making here is that there is both a need and an opportunity to adopt compound resilience policies.”

“These are policies that can help communities grow while improving quality of life,” Galik says.

“For example, we know that incorporating greenhouse gas efficiency measures into new construction is substantially less expensive than retrofitting existing structures,” says Sanchez. “These measures improve energy efficiency and ultimately reduce costs for property owners. Thinking about these ways to improve efficiency at the same time we are thinking about ways to build climate resilience, such as fire resistance or flood mitigation, present tremendous advantages for local governments and the people who call those places home.”

Journal Reference:

Galik, C.S., Sanchez, G.M., ‘Compounded resilience: a step towards achieving climate mitigation and adaptation in the U.S. built environment’, Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 31, 7 (2026). DOI: 10.1007/s11027-025-10273-2

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by North Carolina State University (NCSU)

— Press Release —

Indigenous-led conservation efforts match or surpass similar initiatives when properly funded, new research shows

Federally funded Indigenous-led conservation programs are delivering highly effective climate and biodiversity outcomes, aligning with national greenhouse gas mitigation and biodiversity goals, according to a new paper led by Concordia researchers.

Writing in the journal Earth’s Future, the authors say these programs, as Indigenous-led Nature-based Solutions (NbS), can be just as or even more effective at carbon storage and biodiversity conservation as conventional national and provincial parks.

“Most of the knowledge we have about Indigenous-led conservation efforts comes from countries in the tropics,” says lead author Camilo Alejo, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Geography, Planning and Environment. “We want to explore the effect of government support on Indigenous-led initiatives in the Canadian context.”

Comparing vast areas

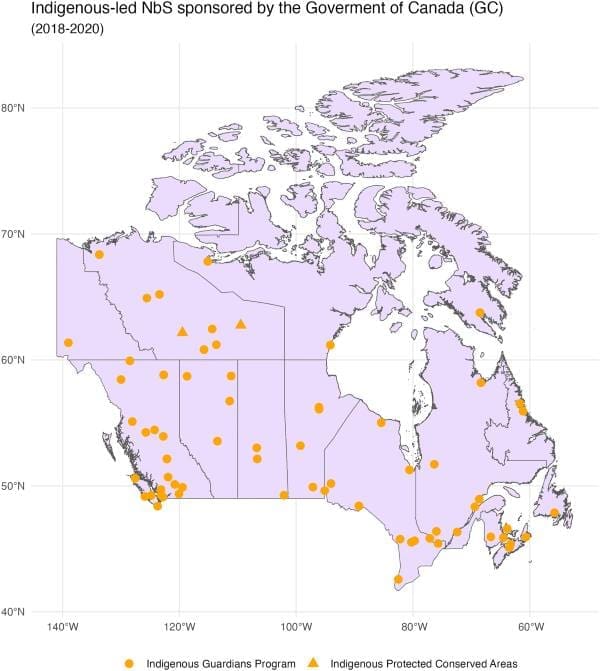

The study examines two Indigenous-led NbS: the Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCA) and the Indigenous Guardians programs.

The IPCAs were established in 2018 and consist of vast regions of land and water in the Northwest Territories. They are administered by local Indigenous Nations using Indigenous laws and traditions and ensure that the peoples there maintain their relationship with their lands. The two IPCAs the researchers studied – Thaidene Nëné on the eastern arm of Great Slave Lake and Edéhzhíe to its west – together cover some 40,000 square kilometres.

The $125-million Indigenous Guardians program was launched in 2017. It has funded over 240 initiatives that act as “eyes and ears on-the-ground,” monitoring ecological health, maintaining cultural sites and protecting sensitive areas and species. All of them are led by First Nations, Inuit or Métis communities.

To carry out the study, the researchers combined national-scale data on forests, vegetation, soils, wildlife habitat and land use with information on Indigenous-led initiatives funded between 2018 and 2020.

They compared three types of land: government-funded Indigenous lands, Indigenous lands without federal funding and conventional protected lands, such as national or provincial parks.

The team used geospatial analysis to map carbon stored in plants and soils and calculated a biodiversity index that included species richness, rarity and ecological intactness. The different land areas were made as comparable as possible using statistical methods, which provided a clearer picture of the effects of Indigenous governance over the areas under their management.

Finally, the researchers analyzed descriptions of Indigenous-led projects to identify common themes. Three principal themes emerged: stewardship practices, including traditional fire practices of controlled burns, knowledge exchange and climate adaptation.

These analyses showed that federally funded Indigenous-led efforts at conserving carbon and biodiversity matched or exceeded outcomes in protected areas. Indigenous-led saw significantly lower carbon loss between 2017 and 2020 than these other areas while keeping biodiversity levels stable, improving on pre-funding carbon trends.

The study did not look at what caused emissions to rise or fall, but land transformation driven by human activity like logging and forest fires were believed to be contributors.

Border issues

The researchers noted conservation project descriptions often linked environmental benefits to Indigenous governance, intergenerational knowledge sharing and climate and biodiversity initiatives.

However, they also say ongoing issues around land tenure, ownership and jurisdiction risk complicating conservation works.

“This study shows that Indigenous-led conservation is an effective mechanism to generate positive environmental outcomes,” says co-author Damon Matthews, a professor in the Department of Geography, Planning and Environment.

“Government funding improves these outcomes. But we have to address issues of land tenure and control on top of that.”

Assembly First Nations strategic advisor Graeme Reed at York University contributed to this study.

***

The Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and Microsoft supported this research.

Journal Reference:

Alejo, C., Reed, G., & Matthews, H. D., ‘Indigenous-led nature-based solutions align net-zero emissions and biodiversity targets in Canada’, Earth’s Future 13, e2025EF006427 (2025). DOI: 10.1029/2025EF006427

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Patrick Lejtenyi | Concordia University

— Press Release —

AI river forecasts may be accurate – but based on flawed logic

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is changing how we predict river flow – but a new study led by researchers at the University of British Columbia shows that these models often get the right answers for the wrong reasons.

The researchers looked at deep-learning models called LSTMs, which are widely used to forecast how rivers respond to changes in rain, snow and temperature. These models are praised for their accuracy, but the study found that their internal “thinking” often clashes with basic science.

“Accuracy alone isn’t enough,” said Dr. Ali Ameli, assistant professor in UBC’s Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, and corresponding author of the paper. “If a model predicts a rain-fed river spike during a heatwave without rain, that’s a problem. We need forecasts that reflect the physics of water movement through the landscape.”

Accurate river forecasts are critical for flood warnings, drought planning and water management. If AI models misinterpret how heat and evaporation affect rivers, communities could face poor decisions during extreme weather – such as unnecessary reservoir releases or missed flood alerts. As climate change brings more heatwaves and shifts in snowmelt, getting these predictions right is essential for safety and sustainability.

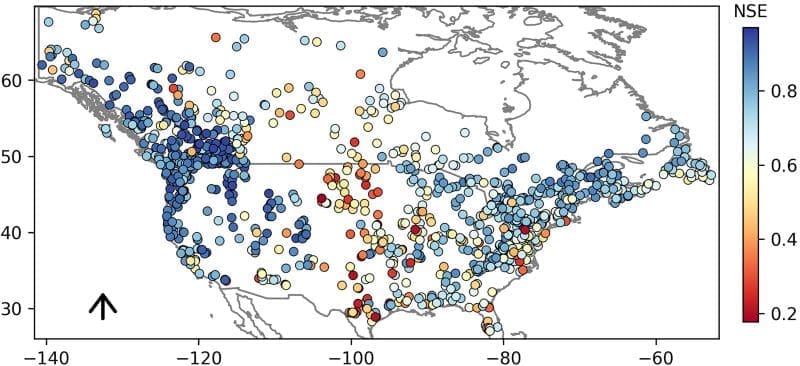

The team analyzed more than 1,100 rivers across North America and focused on 672 where the AI achieved strong predictive accuracy. They built a new tool to peek inside the black box and see how the models link rain, temperature, and PET (short for potential evapotranspiration, the atmosphere’s demand for water) to river flow. The results were clear: While the models handled rainfall correctly, they frequently misinterpreted the roles of temperature and evaporation.

Put simply, in rainy regions, the models sometimes assume that heatwaves or dry air make rivers rise – even when no rain falls. In snowy regions, they often treat PET as the main trigger for snowmelt, instead of temperature. These patterns are not physically realistic.

The study also raises concerns about long-term climate projections made using state-of-the-art AI methods. As global temperatures rise, the relationships among rain, snow, temperature and evaporation will change. If models are built on flawed logic, their predictions for future water availability could be unreliable.

To uncover these issues, the researchers developed a hydrology-specific ‘explainable AI’ framework. This method isolates the effect of each factor – rain, temperature and PET – on river flow, showing whether the model’s reasoning makes sense. Across most regions, the models consistently linked short-term temperature spikes and PET increases to higher river flow, even in places where that shouldn’t happen.

“We’re not saying abandon deep learning,” Dr. Ameli said. “We’re saying check it. Build safeguards so models learn the right physics. With better inputs and physical constraints, AI can be a powerful tool for water forecasting.”

The team suggests practical fixes: Remove seasonal patterns that confuse the models, add missing physical factors like glacier melt, embed the physics of water movement in the AI algorithms, and use diagnostic tools to screen models before they’re deployed. These steps can help ensure that strong accuracy reflects sound physics – not shortcuts in the data.

The study, published in Water Resources Research, was led by UBC PhD student Ara Bayati, with corresponding author Dr. Ali Ameli from UBC and co-author Dr. Saman Razavi from the University of Saskatchewan.

Journal Reference:

Bayati, A., Ameli, A. A., & Razavi, S., ‘Evaluating the functional realism of deep learning rainfall-runoff models using catchment hydrology principles’, Water Resources Research 62, e2025WR040076 (2026). DOI: 10.1029/2025WR040076

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of British Columbia (UBC)

— Press Release —

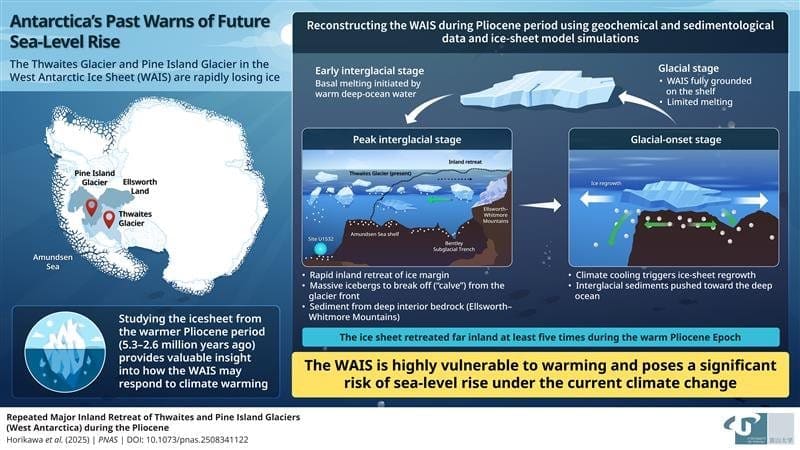

Clues from the past reveal the West Antarctic Ice Sheet’s vulnerability to warming

The Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers, located in the Amundsen Sea sector of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS), are among the fastest-melting glaciers on Earth. Together, they are losing ice more rapidly than any other part of Antarctica, raising serious concerns about the long-term stability of the ice sheet and its contribution to future sea level rise.

To better understand the risks that warmer conditions pose to the WAIS, researchers are looking back to the Pliocene Epoch (5.3–2.58 million years ago), when global temperatures were about 3–4 °C higher than today and sea levels stood more than 15 meters higher, with melted ice from Antarctica contributing to much of that rise.

Now, examining a deep-sea sediment from this region, researchers from the Expedition 379 Science Party, found that the WAIS margin retreated far inland at least five times during the Pliocene period.

The study was led by Professor Keiji Horikawa from the Faculty of Science, University of Toyama, Japan, and included Masao Iwai (Kochi University), Claus-Dieter Hillenbrand (British Antarctic Survey), Christine S. Siddoway (Colorado College), and Anna Ruth Halberstadt (University of Texas at Austin).

The findings, made available online on December 22, 2025, and published in Vol. 123 of the journal PNAS on January 6, 2026, highlight the vulnerability of the WAIS to future warming.

“We wanted to investigate whether the WAIS fully disintegrated during the Pliocene, how often such events occurred, and what triggered them,” says Prof. Horikawa.

The team analyzed marine sediments collected during the IODP Expedition 379. The sediments recovered from the Site U1532 on the Amundsen Sea continental rise act as a historical archive, recording changes in ice sheets and ocean conditions over millions of years.

They identified two distinct sediment layers reflecting alternating cold and warm climate phases: thick, gray, and finely laminated clays from cold glacial periods, when ice extended across much of the continental shelf; and thinner, greenish layers formed during warmer interglacial periods. The green color comes from the microscopic algae, indicating open, ice-free ocean waters. Crucially, these warm-period layers also contain iceberg-rafted debris (IRD), small rock fragments carried by icebergs, that broke off from the Antarctic continent. As these icebergs drifted across the Amundsen Sea and melted, they released this debris onto the seafloor.

The team identified 14 prominent IRD-rich intervals between 4.65 and 3.33 million years ago, each interpreted as a major melt event when the WAIS partially retreated.

To determine how far inland the ice had retreated, the researchers analyzed the chemical “fingerprints” of the sediments. They measured isotopes of strontium, neodymium, and lead, which vary depending on the age and type of the source rock. By comparing these signatures with those of modern seafloor sediments and bedrock samples from across West Antarctica, the team traced much of the debris to the continental interior, particularly the Ellsworth-Whitmore Mountains.

The sediment record reveals a consistent four-stage cycle of warming and cooling. During cold glacial periods, the ice sheet was extensive and stable, covering the continent. As the climate warmed, during the early interglacial stage, basal melting began, leading to the inland retreat of the ice sheet. At peak warmth, during the peak interglacial stage, large icebergs calved from the retreating ice margin and transported sediment from the Antarctic interior across the Amundsen Sea. As temperatures cooled again, during the glacial-onset stage, the ice sheet rapidly regrew, pushing previously deposited sediments toward the shelf edge and transporting them further downslope into deeper waters.

“Our data and model results suggest that the Amundsen Sea sector of the WAIS persisted on the shelf throughout the Pliocene, punctuated by episodic but rapid retreat into the Byrd Subglacial Basin or farther inland, rather than undergoing permanent collapse,” says Prof. Horikawa

The findings indicate that the WAIS has undergone retreats far beyond its current extent, underscoring its extreme vulnerability to future warming and its potential to drive substantial sea level rise.

Journal Reference:

K. Horikawa, M. Iwai, C. Hillenbrand, C.S. Siddoway, A.R. Halberstadt, E.A. Cowan, M.L. Penkrot, K. Gohl, J.S. Wellner, Y. Asahara, K. Shin, M. Noda, M. Fujimoto, & Expedition 379 Science Party, ‘Repeated major inland retreat of Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers (West Antarctica) during the Pliocene’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A. 123 (1) e2508341122 (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2508341122

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Toyama

Featured image credit: Freepik (AI Gen.)