Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press roundup (November 24, 2025), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

New study looks at (rainforest) tea leaves to predict fate of tropical forests

The results, published in JGR Biogeosciences, are encouraging: The researchers learned that tropical forests may be less sensitive to climate change than originally feared.

“Experiments like these will help us improve the models that predict not only how tropical forests will respond to future warming, but also what Earth’s climate will look like in the future – even here in Arizona,” said Ben Wiebe, a doctoral student in ecoinformatics at NAU and second author on the study.

Reading the tea leaves

The study, led by Chris Doughty, an ecoinformatics professor at NAU, built on prior work in Nature that found some leaves in tropical forests could become hot enough to die under future climate change. Widespread leaf death in tropical forests could be accelerated if, when one leaf dies, it heats up the living leaves around it. However, no one had tested this at the top of a rainforest canopy before.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers submerged living canopy top leaves from a Panamanian rainforest in boiling water while the leaves were still attached to the trees. In collaboration with the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, the researchers used a canopy crane to access to the uppermost canopy leaves of multiple tree species. Submerging the leaves in boiling water was the quickest, easiest way to kill them from heat death, which replicates future climate change-driven heat death. They then monitored the surrounding leaves.

Over time, the researchers saw that dead leaves did heat nearby leaves but less than expected because when leaves died, they also got much brighter. Dead leaves will not cool themselves by evaporating water, but they cool themselves by reflecting more of the sun’s energy away.

“This unexpected result is good news because it means that upon death, leaves do not heat up surrounding leaves as much as we thought, so tropical forests may be less sensitive to climate change,” Doughty said. “While boiling leaves at the top of the canopy may sound unconventional, this method of reading the tea leaves delivered insights that bring us closer to understanding the future of tropical forests.”

While at the top of the canopy, the researchers studied what happens if leaves get darker. In prior work, members of the team found that climate change might lead to thinner, darker leaves. The team tested this by artificially darkening canopy top leaves with charcoal. A darker leaf would either evaporate more water to maintain its temperature or get hotter, but it was unclear which outcome would happen. The team found that the leaves mainly evaporate more water, but this is different from predictions by Earth System models. This simple difference could lead to different future climates predictions.

“It may seem silly to boil leaves at the top of a rainforest, but it actually led to some results that can help us to understand the future fate of these bastions of carbon and biodiversity,” said Smithsonian Tropical Forest Researcher Martijn Slot.

Journal Reference:

Doughty, C. E., Wiebe, B. C., & Slot, M., ‘Experimental manipulations of albedo and mortality of upper canopy leaves in a tropical forest diverge from Earth System model results’, Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 130, 11: e2024JG008495 (2025). DOI: 10.1029/2024JG008495

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Northern Arizona University (NAU)

Study identifies molecular changes associated with hotter weather and preterm birth

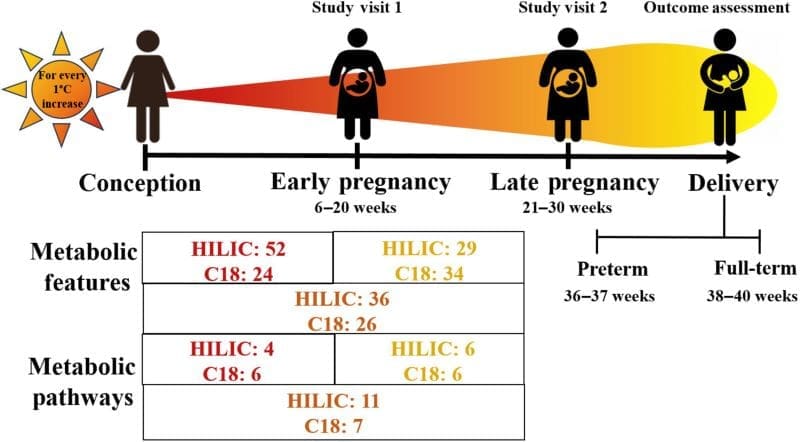

A team of researchers from Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health and School of Medicine conducted a novel molecular analysis of blood samples from 215 pregnant women living in metropolitan Atlanta, whose pregnancies ended in either full-term or pre-term live births (delivery before 37 weeks of pregnancy), and then matched the mothers’ residential addresses with the maximum ambient temperature experienced throughout their pregnancies.

This first-of-its-kind analysis found that several naturally occurring substances, such as methionine, proline, citrulline, and pipecolate, are disrupted when temperatures are higher. These amino acids and vitamins play key roles in managing stress and energy in the body, suggesting that heat-related biological strain may increase the risk of preterm delivery.

Previous scientific evidence suggested hotter weather impacted biological factors such as oxidative stress, heart and vascular issues, inflammation, and the premature rupture of membranes. However, this was the first study to pinpoint the potential molecules and pathways associated with heat and premature birth outcomes.

“As temperatures have increased, we’ve observed an increased association between more babies being born preterm after the weather was hotter, but scientists still don’t know what exactly is happening in the body – and we really need to understand this to develop effective ways to protect mothers and babies,” says study lead author Donghai Liang, PhD, associate professor of environmental health at Rollins.

“We used the innovative metabolomic technology to specifically focus on the small molecules, or ‘molecular fingerprints’ as we call it, and learned for the first time that when the weather was hotter, the mothers’ blood shows some measurable changes in several important molecules and pathways that manage how the body deals with stress or makes energy. And these same kinds of changes were also seen in those mothers who gave birth prematurely.”

Preterm birth is a leading cause of infant illness and death, but little is known about the biological reasons behind it, especially in relation to environmental stressors.

“By identifying these shared metabolic pathways between hotter temperatures and preterm births, this study could open the door to developing early biomarkers that could help identify pregnancies at higher risk and potentially inform prevention strategies or clinical interventions to support healthier pregnancies,” Liang says.

Journal Reference:

Kaitlin R. Taibl et al., ‘Critical windows of prenatal heat exposure and preterm birth: Metabolomic study in the Atlanta African American Maternal-Child Cohort’, Science Advances 11, 47: eadw8328 (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adw8328

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Rob Spahr | Emory University

Cute little marsupials pack a punch at mealtimes

Native Australian animals range from high-hopping kangaroos to fast-running emus – but clever little bettongs also have a special ability to find and eat the food they love.

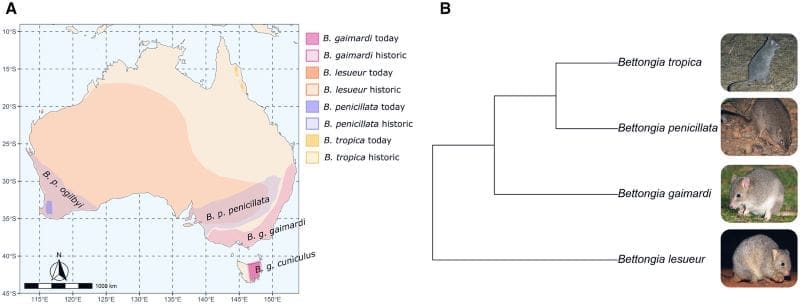

Flinders University researchers have discovered the secrets behind a superpower of these tiny relatives of kangaroos which allows them to crack open seeds that would break the jaws of most animals. They hope the research will help conservation efforts, including finding suitable locations to reintroduce populations severely impacted by predation and habitat loss.

The new study, published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, reveals how two species of these threatened bettongs possess different adaptations to enjoy one particularly tough favourite food of theirs – Santalum seeds, which include the sandalwood, and Australia’s native peach (or quandong).

First author Maddison Randall, Flinders University PhD candidate, says the rabbit-sized marsupials are essential to their environments, spending most of their time digging in search of soft foods such as underground fungi, roots and tubers.

While most bettongs typically feed on softer foods, the burrowing bettong (Bettongia lesueur or ‘boodie’) and the brush-tailed bettong (Bettongia penicillata or ‘woylie’), are also known to crack open the tough outer shells of sandalwood and quandong seeds to obtain the nutritious kernels from inside.

“These seeds are extraordinarily tough, needing bite forces much higher than typical rabbit-sized animals can produce to crack them open,” says Ms Randall, from the College of Science and Engineering.

“We expected the skulls of these tiny animals to have jaw adaptations that can handle higher bite forces but were surprised to find that the two seed-cracking species have developed different biting adaptations to solve the same tough-shelled challenge.”

The team scanned 161 bettong skulls from museums across Australia, including all four living species in the genus, with the eastern bettong (Bettongia gaimardi) and the northern bettong (Bettongia tropica). Using these digital reconstructions of the skull scans, they were able to compare skull shape across the genus using 3D shape analysis.

Flinders University Professor Vera Weisbecker, who co-authored the study, says the jaw adaptations of the two closely related species were not as similar as expected.

“The boodie has a shorter face than the other species. This gives it more leverage, allowing harder biting. But the woylie doesn’t have a shorter face. It instead has a reinforced part of the skull where biting the seeds takes place,” she says.

Another co-author Dr Rex Mitchell adds the difference in snout length may be because the woylie, unlike the boodie, also relies much more on underground fungi (truffles). Thus, their longer snout might help them sniff these out by providing more surface area inside their noses for their sense of smell.

“Understanding animal dietary needs and their associated adaptations is invaluable information for conservation of threatened species,” says Dr Mitchell.

“All four species of bettong around today are threatened to some degree and have been reduced to a fraction of their range since European settlement.

“Therefore, information about their dietary needs, limits and capabilities is vital for conservation and could be used to inform suitable habitat for reintroduction initiatives.”

Bettongs’ other superpower is their major role as ecosystem engineers, with their digging and foraging behaviour turning over soils and leaf litter which improves soils health, water filtration, seed germination and, ultimately, helps ecosystems thrive.

Despite their struggling numbers, these tiny but mighty marsupials are a powerful reminder that there’s more than one way to crack a tough nut.

Journal Reference:

Maddison C Randall, Vera Weisbecker, Meg Martin, Kenny J Travouillon, Jake Newman-Martin, D Rex Mitchell, ‘Cracking the case: differential adaptations to hard biting dominate cranial shape in rat-kangaroos (Potoroidae: Bettongia) with divergent diets’, Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 205, 3: zlaf158 (2025). DOI: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaf158

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Flinders University

AMS Science Preview: Railways and cyclones; pinned clouds; weather warnings in wartime

The American Meteorological Society continuously publishes research on climate, weather, and water in its 12 journals. Many of these articles are available for early online access–they are peer-reviewed, but not yet in their final published form. Below are some recent examples of online and early-online research.

Remote Effects of Urbanization on Temperatures in Adjacent Cities: A Case Study in Utah

Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology

Adjacent urban areas appear to exacerbate each other’s heat island effects. A modeling study of greater Salt Lake City (SLC) and the smaller Utah cities of Ogden and Provo suggests that SLC may raise the temperature in neighboring urban areas by up to 1 °C. The smaller cities also amplify heat effects in SLC.

The Critical Need for Hindcast Infrastructure in Climate Science and Sectoral Applications

Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society

U.S. hindcasting infrastructure is “fragile and underfunded” compared with Europe. Re-running an old forecast with a new component added (hindcasting) allows researchers to correct errors and test how much a new technique or technology improves forecasting. Hindcasts are vital to many sectors, yet this paper’s authors find that the forecast archives on which U.S.-specific hindcasts depend are patchy and underfunded.

“The U.S. currently has an underfunded, fragile hindcast archive infrastructure upon which a tremendous amount of investment and decision support depends. It is critical that our hindcast archive infrastructure be brought into the 21st century.”

Monitoring Microscale Heat Stress Patterns in a Medium-Dense Urban Area with Green Spaces

Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology

Trees beat buildings for urban shade. This study finds that consumer-grade portable measurement devices can provide useful assessments of wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT, a heat stress measure) across urban “microenvironments.” Using these observations, the authors found that buildings either increased or decreased urban WBGT depending on the side of the building measured; tree shade decreased WBGT by 3.5 °C., making trees more reliable against heat stress. At night, unpaved surfaces reduce heat stress by 0.8 °C WBGT.

Assessing Tropical Cyclone Risks to China’s High-Speed Rail Network

Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology

China’s high-speed rail network is vulnerable to tropical cyclones. 42.7% of the China Railway High-speed (CRH) network is exposed to areas with elevated tropical cyclone risk, and 26 of the 30 busiest CRH lines face elevated risks across multiple sections of their routes, the authors find. The Beijing–Shanghai line, the busiest in the network, exhibits risk exposure across 99.8% of its total length, underscoring the need to improve resilience and warning systems.

Pinned Clouds over Industrial Sources of Heat during TRACER

Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society

Industrial facilities create “pinned clouds.” Stereo cameras in a research campaign monitoring aerosols and convection in Houston, Texas, show that around dawn, seemingly stationary plumes of cloud often appear over gas-fired power plant facilities. These “pinned” clouds are not steam emanating from industrial chimneys but rather the result of air rising after being warmed over industrial heating sources. They can stay in the same place for over an hour.

What are the Costs of Heat Spell Mortality in Europe’s Urban Areas up to 2050?

Weather, Climate, and Society

Heatwaves, pollution interact to drive up cardiopulmonary deaths. Heat-related cardiopulmonary disease (CPD) deaths could triple by mid-century in Europe and Asia minor, costing €90 billion annually in welfare economic costs. The study also finds a strong link between air pollution and heat-related CPD deaths, suggesting that combating air pollution could prevent up to 190,000 heat-related deaths by 2050.

Weathering Conflict: Impacts and Solutions for Protecting Hydrometeorological Infrastructure during Armed Conflict

Weather, Climate, and Society

Armed conflict compromises forecasts and disaster warnings. Damage to weather observing stations and similar infrastructure by armed groups exacerbates disaster risk in conflict zones, according to an analysis of weather and water data combined with conflict reports and expert interviews. The authors found that “conflict limits the collection, protection, and storage of hydrometeorological observations, which are crucial for producing weather forecasts and warnings [and that] hydrometeorological infrastructure has been directly destroyed and damaged by armed groups.”

Characterizing the Relation between Lightning and Wildfires in the Western United States

Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology

Fire-igniting lightning strikes are flashier. Lighting flashes that ignite wildfires are “larger and 3–4 times brighter” than average strikes, and tend to come from weaker, drier storms, according to a study of U.S. western wildfires using data from the National Lightning Detection Network, Geostationary Lightning Mapper, and radar. The study also finds that 11% of ignition-causing flashes have been misclassified as intra-cloud strikes.

Amplified Global Seasonality in Water Availability over Land in Recent Decades

Journal of Climate

Dry seasons getting drier with global warming. Using data from 2000 to 2020, the authors find that the range of seasonal water availability has increased significantly worldwide, primarily driven by water availability minimums sinking lower (with ever-higher levels of evaporation compared with precipitation). According to the authors, this “underscores the growing imbalance in global seasonal water availability with climate warming.”

Convective Mode Classification and Distribution of Contiguous United States Tornado Events from 2003–2023

Weather and Forecasting

Tornado weather changes. Analysis of 2003–23 data reveals different distributions for two tornado-producing weather types. Supercell thunderstorms that produce tornadoes were more frequent over a wider area of the U.S., but declined in frequency over the study period. Quasi-linear convective systems (QLCS) that produce tornadoes were concentrated further to the East; QLCS tornado frequency increased over the measured period, though these tornadoes tended to be weaker.

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by American Meteorological Society (AMS)

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay