Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press roundup (December 3, 2025), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

Tropical Australian study sets new standard for Indigenous-led research

Published in Ocean & Coastal Management, the study found the 300 hectares of mangrove forest on the Barron River estuary around Cairns Airport – on the doorstep of the Great Barrier Reef – stores more than 2,000 tonnes of carbon annually, making ongoing care and monitoring of these and other coastal wetlands important for slowing climate change.

The research was co-designed by the Yirrganydji Traditional Custodians along with Blue Carbon Lab and RMIT University scientists and Cairns Airport.

Study lead author from RMIT University, Dr Micheli Costa, said the project was about more than just mangroves and carbon, it was about bringing together different forms of knowledge and strengthening capacity for long-term monitoring of ecosystem change by the Yirrganydji Land and Sea Ranger Program.

“It’s about showing what respectful, co-designed research can look like when Traditional Custodians, scientists, and industry work together with shared purpose,” she said.

“This collaboration created space for cultural leadership, capability building, and knowledge exchange; and that’s what makes it truly impactful.”

Yirrganydji man Brian Singleton, who led the project on behalf of the Yirrganydji Land and Sea Ranger Program, agreed.

“This project was special because it brought together our knowledge with scientific research, right here in a place that is deeply meaningful to us,” he said.

“For generations, Yirrganydji people, guided by our Elders and ancestors, have cared for Country and kept a strong connection to our mangrove systems. Seeing our young people demonstrate such dedication and knowledge made me proud. We’re still learning about blue carbon, but now we have a better understanding of how our stewardship helps protect these places for future generations, and we are learning how to work together with a wide range of partners. We look forward to continuing this journey together.”

Cairns Airport Chief Executive Officer Richard Barker said the airport’s unique location made it vital for the business to do its part in protecting and understanding the environment, in addition to daily operations.

“The landscapes of Tropical North Queensland are world-renowned and our natural attractions, like the Great Barrier Reef and Daintree Rainforest, are key drawcards for visitors. Mangroves play an important role in the health of the overall system and protect the airport physically from storm surge and erosion,” he said.

“Critically, almost two years ago, we experienced firsthand the effects of severe natural disasters through the floods, and we understand how important it is to reduce our risks by strengthening our natural defenses. The team at Cairns Airport is proud to support the important work being done on blue carbon research, as part of a range of strategies we’ve implemented to help fortify the environment and futureproof our operations.”

Cairns Airport Environment Manager Lucy Friend said the study was the first of its kind at this scale in the area.

“This project was truly co-designed,” she said.

“Working side-by-side in the mangroves gave us an opportunity to combine unique perspectives from the corporate sector, research, and Traditional Knowledge. That genuine collaboration strengthened the project and carried through to co-authoring and publishing the paper together, a first for many of us, and it produced stronger data and a study more relevant to everyone.”

Mangrove forests in Far North Queensland are highly diverse, with more than 14 species co-existing in the tidal zone.

Blue Carbon Lab founder and now head of RMIT’s Centre for Nature Positive Solutions, Professor Peter Macreadie, said the study would provide significant new data for projects across tropical Australia and encourage ongoing local research.

“Mangroves have been identified as a key natural climate solution and their conservation and restoration play an important role in emissions reduction,” he said.

“This project was unique, because it was carried out collaboratively with members of Cairns Airport and the Yirrganydji Land and Sea Ranger Program. Working close together, we gained greater insight into the area’s cultural significance and could provide the rangers with methods and equipment to enable ongoing studies around Cairns Airport.”

Journal Reference:

Micheli D.P. Costa, I. Noyan Yilmaz, Pawel Waryszak, Rory Crofts, Melissa Wartman, Pere Masqué, Brian Singleton, Gavin Singleton, Ashlyn Skeene, Lucy Friend, Peter I. Macreadie, ‘Indigenous stewardship and co-management in action: a case study on blue carbon from a mangrove ecosystem on the Great Barrier Reef’, Ocean & Coastal Management 271, 107971 (2026). DOI: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2025.107971

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by RMIT University

Could water, sunlight, and air be all that’s needed to make hydrogen peroxide?

The research published in the journal Nature Communications.

“Currently, hydrogen peroxide is made through the anthraquinone process, which relies on fossil fuels, produces chemical waste and requires transport of concentrated peroxide – all of which have safety and environmental concerns,” said Alireza Abbaspourrad, associate professor of Food Chemistry and Ingredient Technology, and corresponding author of the research.

Hydrogen peroxide is ubiquitous in both industrial and consumer settings: It bleaches paper, treats wastewater, disinfects wounds and household surfaces, and plays a key role in electronics manufacturing. Global production runs into the millions of tons each year. Yet today’s process depends almost entirely on a complex method involving hazardous intermediates and large-scale central chemical plants.

According to Amin Zadehnazari, first author and a postdoctoral researcher in Abbaspourrad’s lab, the new research introduces two engineered, light-responsive materials, dubbed ATP-COF-1 and ATP-COF-2, designed to absorb visible light, separate photogenerated charges and drive the conversion of water and oxygen into hydrogen peroxide.

“These materials work efficiently under visible light, are stable and reusable, and point toward a future where hydrogen peroxide could be made locally instead of in large chemical factories,” Zadehnazari said.

This means rather than shipping concentrated hydrogen peroxide from a few mega-factories, industries or even local treatment facilities could one day generate the molecule onsite using solar energy. That shift could reduce greenhouse gas emissions, cut energy usage and improve safety–particularly in remote or resource-limited settings.

“The challenge,” Zadehnazari added, “is that while the existing anthraquinone process is toxic and not clean, it’s cheap. We’re now focusing on how to make this sustainable alternative affordable at scale.”

While the study is still at the laboratory scale, the researchers are now working to scale up the materials, optimize their performance and integrate the system into practical devices.

“It’s an exciting start,” Zadehnazari said. “This method could reshape how disinfectants and water-treatment agents are produced – making them cleaner, safer and more accessible.”

Journal Reference:

Zadehnazari, A., Auras, F., Koumoulis, D. & Abbaspourrad, A., ‘Charge transfer in triphenylamine–tetrazine covalent organic frameworks for solar-driven hydrogen peroxide production’, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-66679-8

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Cornell University

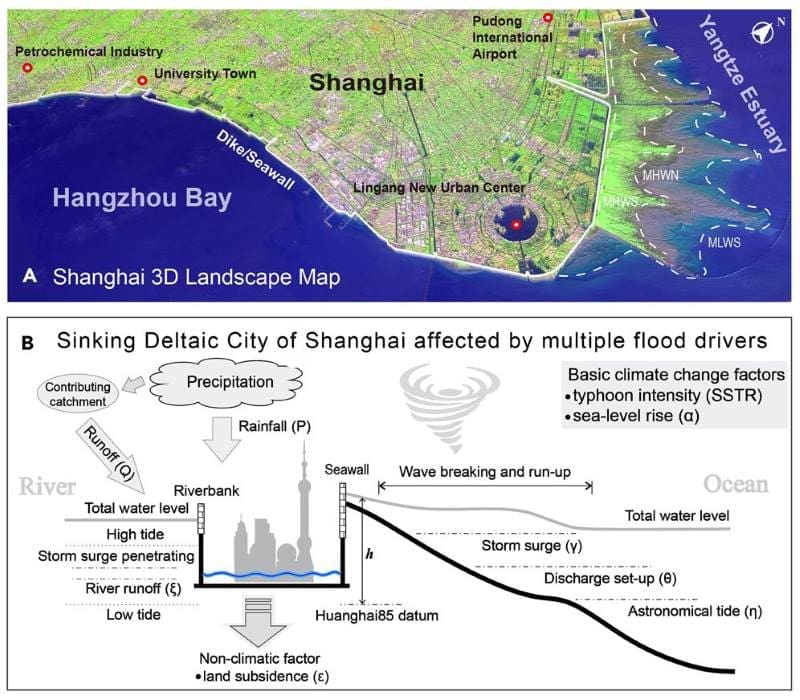

Flood risks in delta cities are increasing, study finds

The study focused on Shanghai, in China, which is threatened with flooding by large and strong typhoons, or tropical storms, producing storm surge and waves.

When these events coincide with other causes of flooding, such as high water flows in the Yangtze River, they can combine to create even more catastrophic floods, as happened with Typhoon Winnie in 1997.

The study was carried out by researchers from the University of East Anglia (UEA), Shanghai Normal University and the University of Southampton, together with other institutions in China, the United States and the Netherlands.

It assessed all the causes of flooding in Shanghai and found that if considering climate, sea-level rise and land subsidence, by 2100 the floods of Shanghai could expand in size by up to 80 per cent and be much deeper.

The authors say that to avoid disaster a major adaptation effort is required, which will almost certainly include raising defences and constructing mobile flood barriers, like those seen at the Thames Barrier in London.

However, they warn there is also the risk of “catastrophic failure” of defences due to rising water levels, especially due to the combination of subsidence, sea-level rise and higher surges during typhoons, as occurred in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

They say this danger is not fully appreciated and must be considered in adaptation in Shanghai and other deltaic cities, with a layered rather than single line of defence needed.

The study, published in the journal One Earth, is the first comprehensive analysis of flooding in a delta city.

“These findings have wider implications for all coastal cities and especially those built on deltas like Shanghai,” said lead UK author Prof Robert Nicholls, of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research at UEA and University of Southampton. “Such analyses are critical to anticipate and support the significant adaptation needs in these cities.”

Low-lying deltas host some of the world’s fastest-growing cities and vital economic centres, but they are increasingly vulnerable to flooding from tropical and extratropical cyclones.

Floods are driven by combinations of tide, storm surge, wave, river flows and rain. The most extreme floods occur due to the simultaneous combination of different sources of flood, such as a high river flow and a storm at the same time.

“The likelihood and magnitude of floods are often underestimated as these combined floods are not considered,” said Prof Nicholls. “Further climate change and land subsidence – all deltas sink – is increasing the likelihood of flooding. Therefore, the threat is growing in all coastal cities and especially delta cities where all these issues occur.”

The team used an atmosphere, ocean, and coast model (AOCM) of the Shanghai region that for the first time includes all the flood drivers. Taking 10 historic typhoon events that produced significant floods, they simulated how they will change over the next 75 years to 2100, with different amounts of climate change and land subsidence.

Lead author Prof Min Zhang, of Shanghai Normal University, said: “We find that the area flooded in a typhoon by an extreme, one in 200-year event – an event that should be considered in disaster risk management and flood planning – could increase by up to 80 percent in 2100.”

“The response to this challenge will almost certainly be raising of defences as Shanghai and most delta cities are already defended. However, rising water levels, especially due to the combination of subsidence, sea-level rise and higher surges during typhoons raise the prospect of catastrophic failure and large, deep floods if the defences fail.”

Prof Nicholls added: “This so-called ‘polder effect’ when defences fail is not fully appreciated. It must be carefully considered in adaptation planning in Shanghai and other deltaic cities. Rather than depending on a single line of defences, layered defence is needed to make these cities more resilient today and into the future.”

Journal Reference:

Zhang, Min et al., ‘Growing compound-flood risk, driven by both climate change and land subsidence, challenges flood risk reduction in major delta cities’, One Earth online, 101489 (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.oneear.2025.101489. Also available on ScienceDirect.

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of East Anglia (UEA)

Rising heat leads to minimal losses for California processing tomatoes

California’s $1 billion processing tomato industry is highly efficient and likely will be able to withstand higher temperatures and traffic congestion with minimal postharvest losses, according to research conducted at the University of California, Davis.

The research, published in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics, analyzed 1.4 million truckloads of tomatoes transported from thousands of farm fields to processing facilities between 2011 and 2020.

“It’s rare that we find an example where climate change is expected to have a negligible effect,” said Sarah Whitnell, who led the research as a postdoctoral scholar at UC Davis and is now at University of Western Australia, Perth. “Ultimately, the supply chain is a well-oiled machine. The losses are relatively small, and while temperature does increase them, it’s not by a huge amount.”

Researchers matched each truckload to California state highway traffic data and hourly temperatures, which ranged from 48 degrees to 108 degrees Fahrenheit. They compared truckloads of tomatoes from the same field and same growing season: for example, one travelling at 5 a.m. when temperatures are cooler and traffic is light with one travelling at 5 p.m. when the opposite is true.

Optimal conditions: Cool weather and traffic

The best-case scenario was when cool temperatures coincided with heavy traffic. The worst-case scenario was hot temperatures combined with heavy traffic. When it’s hot, slow traffic speeds cause trucks to spend more time at damaging temperatures.

“If you have this magic scenario where temperatures are cool but there is traffic, you actually have the lowest losses,” Whitnall said. “This is because faster speeds cause vibrations that can increase damage in fresh produce.”

Comparing best- and worst-case scenarios, the share of soft, split or squished tomatoes doubles from about 1% to 2%. This equates to modest losses, the researchers also found.

The findings show that California’s processing tomato industry is highly efficient and could be a model for others, said senior author Tim Beatty, who is chair of the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics at UC Davis.

“Most supply chains aren’t nearly as efficient as the California supply chain, so what this says is if you’re a very efficient supply chain, you can mitigate the losses associated with climate change,” Beatty said. “It says that adaptation is possible to really reduce loss past the farm gate.”

Industry relationships made research possible

Eighty-four cents of every farm dollar is generated after the product leaves a farm, but most climate change research has focused on how growing is affected. This research looks at that second stage and was possible because of comprehensive public data and detailed transport, tonnage and quality data supplied by industry, Beatty said.

“We know very little about the effects of climate change once product leaves the farm gate,” he said. “I think this paper is one of the very first to actually tackle that.”

***

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agriculture and Food Research Initiative supported this research.

Journal Reference:

Whitnall, Sarah C., and Timothy K. M. Beatty, ‘Postharvest Losses from Temperature during Transit: Evidence from a Million Truckloads’, American Journal of Agricultural Economics online 1–24 (2025). DOI: 10.1111/ajae.70019

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Emily C. Dooley | University of California – Davis (UC Davis)

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay