Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press roundup (January 15, 2026), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

— Press Release —

What most corporate carbon reports get wrong, and how to fix them

A new Stanford-led analysis of corporate carbon disclosures finds companies undercount emissions from their supply chains by billions of tons.

The shortfall arises from use of a popular statistical model that assumes all suppliers are located in the United States. “Supply chains are global, though, so a model that assumes everything is made domestically is going to give us a wrong answer,” said Steve Davis, a professor of Earth system science in the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability and lead author of a new study in Nature Communications.

Davis and co-authors set out to find out how far off estimates are under the common approach compared to results from an alternative model that considers emissions data from the regions where suppliers actually operate. They found widely used single-region U.S. models, such as one maintained until recently by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, miss about 2 billion tons, or 10% of emissions tied to more than 400 companies’ supply chains in 2023. That’s roughly equivalent to the annual emissions of Russia or India.

The additional 2023 emissions included approximately 973 million tons of emissions attributed to suppliers in China, which relies heavily on coal. The biggest gaps emerged in energy-intensive manufacturing sectors such as steel and concrete, construction machinery, fabricated metals used for cars and infrastructure, and electronic components.

Companies relying on estimates from single-region U.S. models may overlook the emissions impact of importing energy-intensive manufactured goods from China and Russia, according to the study. They may also miss opportunities to reduce emissions and associated costs by sourcing those goods from countries with cleaner grids, such as the U.S., France, and Brazil.

At the start of 2026, as an expanded carbon border tariff takes effect in Europe, the cost of upstream emissions is increasing for EU importers of manufactured goods, including steel, aluminum, and cement. “A company that’s interested in reducing the emissions in their supply chain needs to know not just how big the number is, but also where these emissions are coming from,” Davis said.

Expanding access to better data

Together with collaborators including lab member Wesley Ingwersen, who created the U.S. EPA model and led work on it until the agency shuttered it in August 2025, Davis is now working to make a global model freely available and easy to use through an effort called Cornerstone. “The reason companies haven’t been using the global models is they’re not as easy to come by. They are a lot more involved to build, and there hasn’t been an easy, open-source version,” said Davis.

The group is integrating the former government database with the multi-region model analyzed in the study, which was developed by a private company called Watershed, where Davis chairs the science advisory board and previously served as head of climate science.

“When available tools neglect international sources of emissions, companies’ sustainability decisions suffer,” said study co-author Michael Steffen, Watershed’s head of climate analytics.

The team aims to release the merged model in late 2026, with ambitions to account for emissions from land-use changes and deforestation in later research and iterations. “If you’re getting soybeans from Iowa, it has a very different footprint than if you’ve cut down some of the Amazon to grow those soybeans,” Davis said.

Scientists from the World Wildlife Fund and CDP, formerly known as the Carbon Disclosure Project, co-authored the paper. “These are NGOs that are really interested in minimizing greenwashing and making sure that corporate climate actions are as beneficial as possible,” Davis said.

Some critics question whether models based on sector-wide averages and spending like those analyzed in the study are the right approach to estimate upstream emissions at all – regardless of whether global or single-region models are used.

“I think we could all agree that if you had perfect data about exactly what was going on in your supply chain, you could make even more accurate estimates and leapfrog all of these models,” Davis said. “The reality is, though, that it’s still really difficult to get a lot of that data, and there’s little prospect of getting it without much more stringent regulations than are even on the table.” As a result, he said, there’s value in improving the modeling approach even if the long-term strategy is to get better data.

Corporations seeking to track and reduce emissions in their supply chains have the potential to make a meaningful difference in global carbon pollution, Davis said. “They are making sizable investments. If those dollars are directed to the right places, it could meaningfully reduce global emissions,” he said.

Journal Reference:

Davis, S.J., Dumit, A., Li, M. et al., ‘The importance of multiregional accounting for corporate carbon emissions’, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-67759-5

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Josie Garthwaite | Stanford University

— Press Release —

The hidden warming challenge in climate action

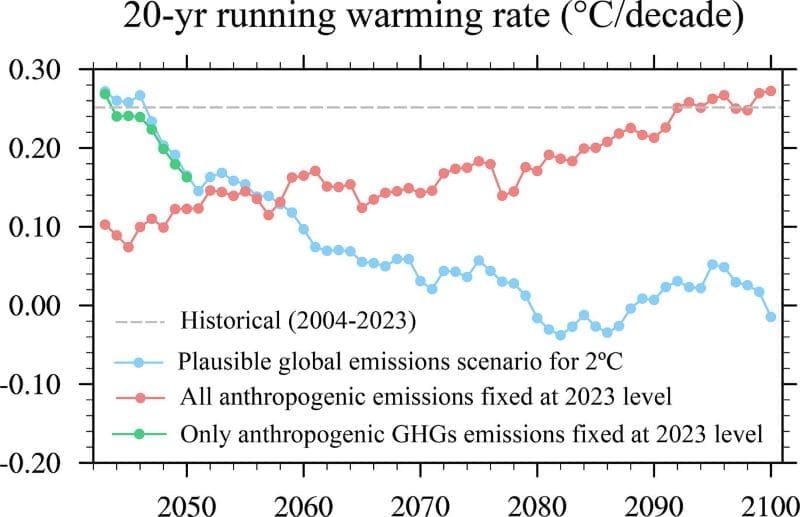

Over the past two decades, global warming has continued to accelerate. In response to the climate crisis, the 2015 Paris Agreement established a global consensus to limit global temperature rise to well below 2 °C by the end of the century. Compared to the initial Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), most parties have submitted updated second-round NDCs since 2020. Against this backdrop, a critical scientific question has emerged: will the accelerating trend of global warming be effectively curbed by current climate actions?

This study, based on a global emissions scenario consistent with China’s net-zero pathway and the 2 °C target, employed the widely used Community Earth System Model version 2 (CESM2) to conduct more policy-relevant climate change projections. The results indicate that even if all parties fully implement the decarbonization targets outlined in the second-round NDCs, the current acceleration of global warming may still not be effectively curbed over the next two decades. The primary reason is the significant decline in atmospheric aerosol burdens co-emitted with greenhouse gases.

Aerosols exert a cooling effect by reflecting solar radiation. A reduction in their emissions weakens this “umbrella” effect, thereby allowing the warming effect of accumulated greenhouse gases – previously partially masked – to become increasingly apparent. The warming acceleration induced by aerosol reduction is particularly pronounced in the Arctic and Eurasia during the Northern Hemisphere winter.

Climate action is crucial for achieving long-term sustainable development: reducing greenhouse gases emissions not only mitigates global warming but also decreases the frequency and intensity of extreme climate events, thereby reducing associated economic losses. Simultaneously, aerosol reduction helps improve air quality and has positive impacts on public health.

However, in the process of advancing the net-zero transition, it is essential to consider the additional climate effect owing to co-reduced aerosols and the resulting risks. The study recommends integrating this factor into comprehensive climate policy assessments to more fully capture the long-term benefits and overall climate effectiveness of emission reduction actions.

Journal Reference:

Yadong Lei, Zhili Wang, Junting Zhong, Xiaochao Yu, Huizheng Che, Xiaoye Zhang, ‘Aerosol reductions boost near-term warming rate in a plausible net-zero transition’, Science Bulletin 70, 24 (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.scib.2025.09.024

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Science China Press

— Press Release —

Recovering tropical forests grow back nearly twice as fast with nitrogen

Young tropical forests play a crucial role in slowing climate change. Growing trees absorb carbon dioxide from the air, using photosynthesis to build it into their roots, trunks, and branches, where they can store carbon for decades or even centuries. But, according to a new study, this CO₂ absorption may be slowed down by the lack of a crucial element that trees need to grow: nitrogen.

Published in Nature Communications and co-authored by Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies ecologist Sarah Batterman, the study estimates that if recovering tropical forests had enough nitrogen in their soils, they might absorb up to an additional 820 million metric tons of carbon dioxide each year for a decade.

“Nitrogen is limiting how quickly young forests can regrow,” said Batterman, senior author on the paper. “When we added nitrogen to the soil, forests grew back almost twice as fast in the first 10 years. Faster growth rates mean faster absorption of carbon dioxide, which can help to give us a few more years to reduce our carbon emissions.”

Rather than fertilizing young forests, the scientists recommend planting nitrogen-fixing trees in regenerating forests and, when possible, prioritizing forest restoration on lands that receive nitrogen pollution from farms and factories.

A giant study

About 50% of tropical forests are recovering from disruptions such as logging, wildfire, and agriculture – all processes that can cause nitrogen to leak out of the soil. Phosphorus is also thought to be a limiting nutrient in tropical forests.

Scientists, led by Wenguang Tang for his graduate research at the University of Leeds, wanted to test how adding nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers would affect the growth rates (and therefore carbon absorption rates) of tree trunks and branches in recovering tropical forests.

The experiment encompassed 76 hockey-rink-sized plots in Panama, each covering 1600 square meters. The plots ranged in maturity at the start of the experiment, including newly regenerating forests, middle-aged forests that had been regenerating for 10 and 30 years, and mature forests with limited human disturbance for hundreds of years. The plots received additional nitrogen, phosphorus, both, or none. Some of the sites have been monitored since 1997.

“Our work represents the world’s largest and longest nitrogen and phosphorus addition experiment of its kind,” said Tang, now at the University of Glasgow. “Each of our 76 plots has been censused at least five times, and in each census, data were collected from more than 20,000 trees. Maintaining high-quality, consistent census data over such a long period and across so many individuals was extremely challenging.”

The nitrogen effect

The team found that adding nitrogen caused the forest to regrow a whopping 95% faster in recently abandoned agricultural fields, and 48% faster in forests that had been recovering for 10 years.

“It was pretty amazing to see,” said Batterman. “The plots with added nitrogen looked so much bigger than the ones where we didn’t add nitrogen – the trees were just huge. We were surprised how quickly the forest grew back and how strong the effect of nitrogen was.”

For the forests 30 years and older, adding nitrogen had no effect, likely because nitrogen had built up in the soil over time, thanks to nitrogen-fixing trees. These trees cooperate with bacteria to pull nitrogen gas out of the atmosphere, converting it into a form of nitrogen that plants can use.

A phosphorus puzzle

Contrary to scientific expectations, adding phosphorus to the soil made no difference to forest growth rates at any age – a striking result, said lead author Tang. “This result challenges the long-standing theory that tropical forest carbon sinks are fundamentally constrained by phosphorus availability.”

It is possible that phosphorus addition did result in changes to the trees’ roots or fruits, which were not measured in this study. Another explanation is that trees in these forests have evolved creative ways to overcome phosphorus limitations. The scientists hope to investigate this thread further, to better understand what strategies trees use to maintain high productivity despite low phosphorus in the soil.

“Future work should also examine how consistent these patterns are in other tropical forests, including in Africa and Asia,” said Tang. “However, we expect nitrogen limitation in young tropical forests may be quite common. It’s likely becoming increasingly important, too, as forest disturbances increase and carbon dioxide levels rise in the atmosphere.”

Putting the research into practice

If nitrogen limitation is indeed widespread, the team estimates it may prevent recovering tropical forests from absorbing an additional 470 to 840 million metric tons of carbon dioxide per year. That’s roughly equivalent to taking 142 million gasoline-powered cars off the road each year.

To achieve those gains, the team does not advocate for adding fertilizer to overcome nutrient limitations. Nitrogen fertilizer is expensive and energy intensive to produce; it can also pollute waterways and lead to emissions of nitrous oxide, a powerful greenhouse gas. Instead, the team recommends being more strategic about where to focus on forest regeneration and which tree species should be planted at these sites.

“Ideally, forest stewards could make sure that some of the trees in a regrowing forest are nitrogen-fixers,” said Batterman.

Another strategy recommended by the team is to prioritize reforestation in areas where there is high nitrogen pollution from agriculture, factories, and transportation. This way, the trees can clean up the nitrogen pollution before it clogs waterways or turns into greenhouse gases, and the forests will grow back faster.

“These practices could increase how quickly these recovering forests take in carbon dioxide,” said Batterman. “In the long-term, the forests are not going to sequester extra carbon, but in that first 10 years, they can do the job faster, and 10 years is what we really need right now. We need to make big changes to reduce our fossil fuel emissions, such as shifting to clean energy and swapping out our gas guzzlers for electric vehicles, and unfortunately, that switch is taking longer than we need it to. Reforestation is one tool that can buy us more time to decarbonize and delay the worst effects of climate change.”

Journal Reference:

Tang, W., Hall, J.S., Phillips, O.L. et al., ‘Tropical forest carbon sequestration accelerated by nitrogen’, Nature Communications 17, 55 (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-66825-2

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies

Featured image credit: Freepik (AI Gen.)