Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press roundup (February 8, 2026), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

— Press Release —

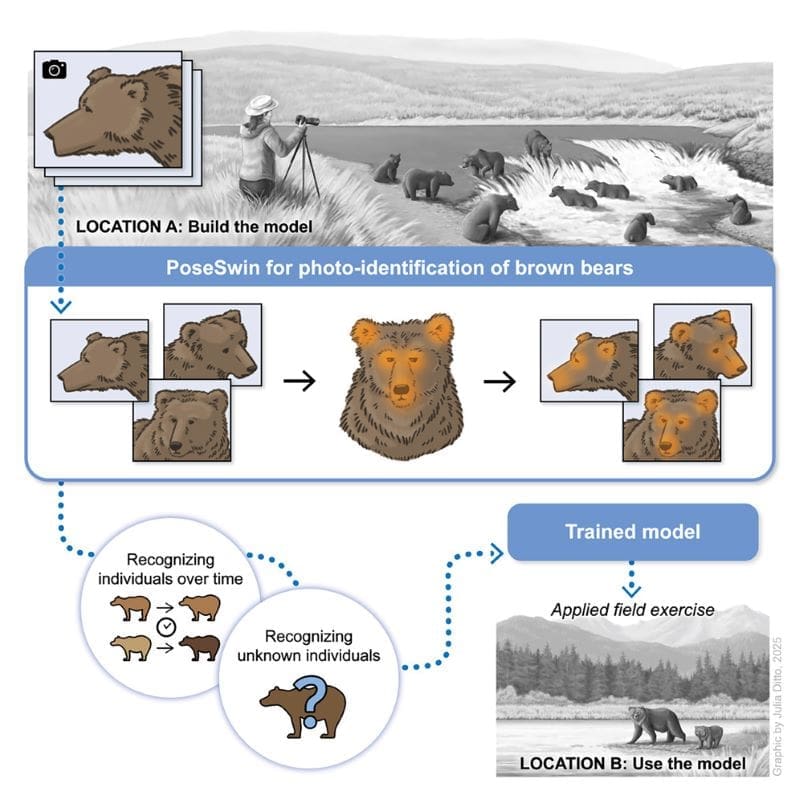

AI enables a Who’s Who of brown bears in Alaska

Being able to distinguish individual animals – including their unique history, movement patterns and habits – can help scientists better understand how their species function, and therefore better manage habitats and study population dynamics.

Today, most computer vision systems for tracking animals are effective on species with patterns and markings, such as zebras, leopards and giraffes. The task is much more complicated for unmarked species where individual differences are harder to spot. Distinguishing a particular brown bear from its peers in a non-invasive way requires an incredible eye for detail and years of viewing the same bears over time.

What’s more, these bears emerge from hibernation in the spring with shaggy fur and having lost quite a bit of weight and then substantially increase their body weight feasting on salmon, as well as fully shedding their winter coat – that’s enough to throw off experts as well as AI algorithms.

A team of scientists from EPFL and Alaska Pacific University has developed an AI program that can recognize individual brown bears over time in photos, despite changes in the bears’ appearance and the difficulties associated with image capture for these elusive and far-ranging animals.

Machine learning based on head and posture

The McNeil River State Game Sanctuary in Alaska is home to the world’s largest seasonal population of brown bears (Ursus arctos). Every summer, nearly 150 of these animals move through this area undisturbed over 500 km² of pristine land. They gather on high-protein sedge meadows, and at large, low-grade waterfalls to catch salmon, providing an opportunity for the few humans allowed in the sanctuary to observe them.

“The latter are strictly supervised; this is bear territory!” smiles Alexander Mathis, a professor at EPFL’s Brain Mind Institute and Neuro-X Institute. This remote area is also home to Beth Rosenberg, a researcher at the Fisheries, Aquatic Science, and Technology Laboratory at Alaska Pacific University, for four months of the year. She has built up an extraordinary database of brown-bear images: between 2017 and 2022, she took over 72,000 photos of 109 different brown bears under all sorts of conditions – in the rain, in varying times of day, and with bears in every available behavior and posture (or angle) – in order to fully depict the bears in their natural habitat.

To develop their AI program, called PoseSwin, the scientists drew on their biological expertise to focus on four characteristics of bears that change surprisingly little over time: the shape of the muzzle (which has minimal fatty tissue), the brow bone angle, and the placement of the ears. Crucially, they incorporated pose information – analyzing photos of bears from various angles including frontal, profile, and tilted views.

“This pose-aware approach enabled us to use as many pictures as possible, even those that do not clearly show the bear’s face perfectly,” says Mathis. “Our biological intuition was that head features combined with pose would be more reliable than body shape alone, which changes dramatically with weight gain. The data proved us right – PoseSwin significantly outperformed models that used body images or ignored pose information.”

Capturing a bear’s true identity

The architecture behind the scientists’ program is based on transformers – the same fundamental technology that powers large language models like ChatGPT – but adapted specifically for image analysis. “We used a technique called metric learning to train a transformer to understand the relationships between different parts of the images,” says Mathis. That means the algorithm learned not only to recognize individual bears based on the characteristics mentioned earlier, but also to compare two images of bears. The team exposed the algorithm to groups of three photos: two of the same bear taken at different times and one of another bear.

The algorithm projected the images onto a multidimensional mathematical space, placing the photos of the same bear near each other and pushing those of the other bears further away. “It is a real game of attraction and repulsion, a digital tug-of-war where images shuffle around until they form coherent groups,” says Mathis. “Each bear ended up being represented as a unique constellation of points, which suggests the AI program was able to capture something fundamental – not just a bear’s appearance but something closer to its identity.”

PoseSwin can also flag bears that it has never seen before, which is a major advantage for studies in unenclosed areas where new individuals can appear regularly.

The next step was to apply the program in a new environment. For that, the scientists turned to citizen science: they collected photos taken by visitors to Katmai National Park and Preserve, located just over 60 km from McNeil River, and fed them into the PoseSwin algorithm. The program clearly recognized several of the bears, indicating specifically where the animals move seasonally in search of food.

“This is a concrete example of the PoseSwin model’s potential,” says Rosenberg. “The technology could eventually be used to analyze the thousands of pictures that visitors take every year and help to build a map of how brown bears use this expansive area. This helps us to understand what they need, how their population dynamics work, and many other important ecological questions.”

“A bear is a complicated version of a mouse”

Thanks to photos of the bears and some virtual measurements of their morphology, scientists are now able to track Sloth, Rocky, That Bear and around 100 of their peers without interfering with them physically. “The better we can distinguish individual bears, the better we can understand them and their behaviors at the species level,” says Rosenberg. “Bears are at the top of the food chain and ensure the proper functioning of their ecosystem. They are critical to maintaining healthy systems.”

PoseSwin will make field work more broadly applicable for the scientists involved in the study, as well as for other scientists working in other contexts. It also achieved excellent accuracy on benchmark datasets of macaques, suggesting its broad applicability beyond bears.

“Bears are perhaps the hardest species to recognize individually,” says Mathis. “We focused on them first with the idea that our program could be adapted to other species from mice to chimps, which seem to exhibit much less visual variation.” The team has provided open-source access to their algorithm and the data used to develop it so that other researchers can use and adapt it as needed.

The scientists plan to continue developing PoseSwin for Alaskan brown bears. Because the program is scalable, they are already able to add data collected in other seasons and from other locations. Their goal is to automate much of the system so that it can help monitor wild animal populations over the long term.

Journal Reference:

Beth Rosenberg, Mu Zhou, Nathan Wolf, Mackenzie Weygandt Mathis, Bradley P. Harris, Alexander Mathis, ‘Individual identification of brown bears using pose-aware metric learning’, Cell Current Biology 36, 3, pp. 645 – 659.e14 (2026). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.12.022

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Cécilia Carron | EPFL

— Press Release —

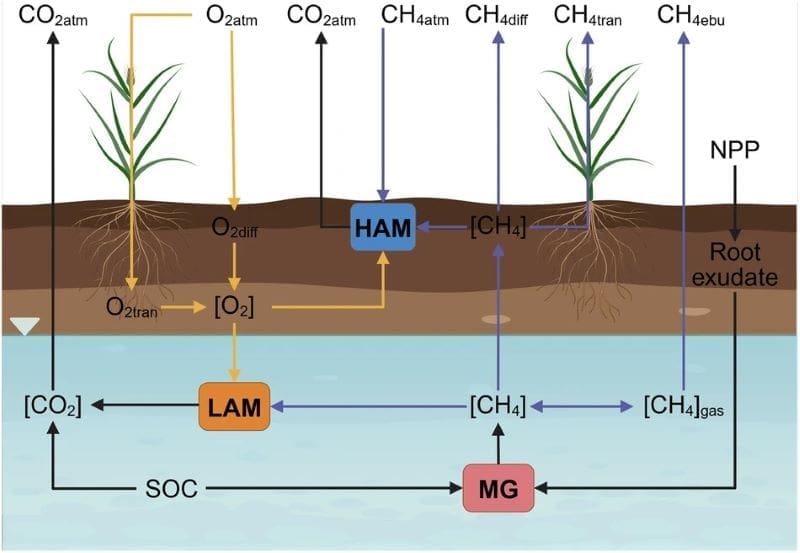

Wetlands do not need to be flooded to provide the greatest climate benefit

Wetlands make up only about six percent of the land area but contain about 30 percent of the terrestrial organic carbon pool. Therefore, CO₂ emissions from wetlands are central to the global climate balance. In Denmark, the plan is to flood 140,000 hectares of low-lying land such as bogs and meadows as part of the Green Tripartite Agreement.

Flooding such areas will slow down the decomposition of organic material in the soil and keep the CO₂ in the soil rather than allowing it to be released to the atmosphere and contribute to the greenhouse effect. At least, that has been the rationale until now.

However, a new study from the University of Copenhagen, published in Communications Earth & Environment, shows that this is not the best solution for the climate. By completely flooding low-lying areas, the optimal conditions are created for the formation of methane – a greenhouse gas that is up to 30 times more harmful to the climate than CO₂.

“Most people currently expect that converted Danish low-lying soils will be flooded on a large scale. But our research shows that this is not a good idea. By keeping the water level slightly below ground level, methane produced can be partly converted to the less harmful greenhouse gas CO₂ before it is released, thereby limiting methane emissions,” says Professor Bo Elberling from the Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, who led the study.

Microorganisms in the soil are an overlooked game changer

Other Danish researchers have mapped microbial life in Danish soils and found a total of 140,000 different species. Some of these microorganisms, which live in the upper soil layers, are the reason why flooding low-lying soils is not a good idea.

Here, methane-oxidizing microbes can convert methane produced deeper down in the very wet soil by other microorganisms, which otherwise would be released to the atmosphere. However, the conversion of methane only takes place if there is oxygen present in the soil. If the upper soil layers are flooded, they quickly become oxygen-free, and the conversion of methane stops.

The new knowledge is based on measurements and modeling in Maglemosen, a wetland located 20 kilometers north of Copenhagen, which has been undisturbed for more than 100 years and in many ways represents a typical Danish wetland with peat soils.

Here, Bo Elberling and his colleagues have measured CO₂ and methane emissions from the soil continuously for several years and have now modelled a 16-year period from 2007 to 2023. The researchers also monitored the water level, plant life and soil and air temperatures. This large database was then used in a model to simulate observations and to investigate the most optimal water level in relation to the emission of both CO₂ and methane.

“Based on our data from 2007 to 2023, we can see that the most climate-friendly water level in Maglemosen is around 10 centimeters below ground level. This is the level that overall provides the best balance between methane and CO₂ emissions,” says Elberling.

The researchers emphasize that the precise recommendation of the depth of the water level will vary from wetland to wetland and will probably be somewhere between 5 and 20 centimeters below ground level. But the main point is clear:

“A stable water level below ground level will almost always provide the greatest climate benefit,” says Elberling.

Engineering task and Dutch experiences

The results thus point to a specific and stable water level in order to hit the climatic “sweet spot” between methane and CO₂. According to the professor, this requires closer monitoring of the water level and some engineering work in order to both drain and supply the necessary water.

“It is clearly a challenge to ensure a stable water level in the new Danish wetlands. Optimum conditions require quite wet conditions but not water to the surface. So, what do you do, for example, in the dry summer months or in the autumn with heavy rain events?” says Elberling.

However, according to the professor, the management of wetlands is far from an unknown problem, and there is some experience to be gained in both Denmark and other countries. He highlights the Netherlands, which is considered the world champion in keeping a constant water level. And, of course, the management of wetlands would ideally rely on green energy.

“The Netherlands would be under water if they did not constantly maintain a fairly stable water table. That is why we should look in that direction. We cannot just flood low-lying areas and then leave the water table to fluctuate freely. It will be a matter of using green energy, such as solar energy, to power pumps that can keep the water level stable,” explains Bo Elberling.

Plant communities and nitrous oxide are also important factors

Changes in plant communities in new lowland areas are also important to consider. Some plants are good at transporting oxygen down into the soil and methane out into the atmosphere via their roots. This is included in the modelling work carried out in Maglemosen, where Canary grass dominates. Like rice plants, Canary grass is known for its ability to transport oxygen and methane within the plant itself.

“In Maglemosen, around 80 percent of the methane is released via the plants, and in particular Canary grass is expected to become more dominant in converted lowland areas in the future. Therefore, this plant species is likely to increase the transport of methane from the soil to the atmosphere, meaning that a smaller proportion of methane will be converted before being released,” says Elberling.

A stable water level is also crucial for keeping emissions low for another important and very potent greenhouse gas, namely nitrous oxide, which is about 300 times more powerful than CO₂ over a 100-year period.

“If the water level in flooded lowlands in the future is allowed to fluctuate at the whim of the weather gods, nitrous oxide emissions could significantly reduce the climate benefits,” concludes Elberling.

The researchers behind the study are Bingqian Zhao, Wenxin Zhang, Peiyan Wang, Adrian Gustafson, Christian J. Jørgensen and Bo Elberling. The researchers are affiliated with the University of Copenhagen, Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, Lund University, Department of Physical Geography and Ecosystem Science, and Aarhus University, Department of Ecoscience.

Journal Reference:

Zhao, B., Zhang, W., Wang, P. et al., ‘Optimized wetland rewetting strategies can control methane, carbon dioxide, and oxygen responses to water table fluctuations’, Communications Earth & Environment 7, 109 (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-025-03163-7

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Copenhagen (KU)

— Press Release —

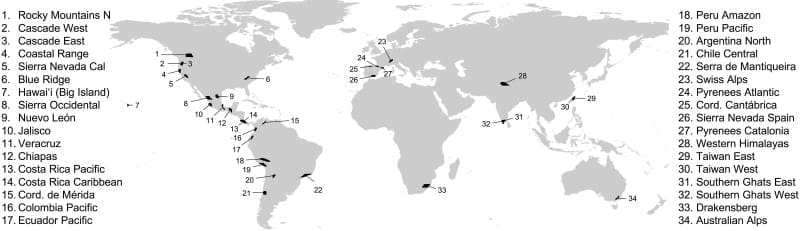

‘Energy efficiency’ key to mountain birds adapting to changing environmental conditions

Scientists know that species diversity changes as you go up a mountain, but it is not clearly understood why this is the case.

One theory is that it is mostly because of long-term evolution, and the climate niches species have adapted to over millions of years. Another – the ‘energy efficiency’ hypothesis – suggests it is about how species today manage their energy budgets and compete for available resources that vary in space and time.

To test this, researchers looked at seasonal changes in the elevational distributions of birds – how high in the mountain birds go at different times of year – for nearly 11,000 avian populations across 34 mountain regions worldwide.

Publishing their findings in the journal Science Advances, they found that many birds do not strictly follow the temperatures they are supposedly adapted to.

Instead, their movements match what would be expected if they were trying to use and acquire energy in the most efficient way based on today’s environments, with computer models simulating what birds should do to save energy corresponding with what they do in real life.

Lead author Dr Marius Somveille, of UEA’s School of Environmental Sciences, said: “A lot of mountain birds perform altitudinal migration – moving up and down the mountain with the seasons. This behaviour is common but not well-studied, and it has long been debated whether environmental conditions and biodiversity change with elevation in the same way they do with increasing latitude.

“We found that energy efficiency appears to drive both the seasonal distribution of birds across latitudes and along mountain slopes. This suggests that elevational gradients in avian distributions might be a condensed version of corresponding latitudinal gradients, and that altitudinal migration serves the same ecological purpose as long-distance migration, like flying towards the tropics for winter, saving energy and surviving in changing conditions.

“Understanding this is important as it helps us better predict how mountain birds will cope with global change.”

Dr Somveille added: “Human activity is affecting where energy and resources are available in mountain environments. Lower elevations are losing habitat due to human activity, while higher elevations stay more protected because they’re harder to reach. These shifts are likely to significantly change where birds can live and how they spread out across mountains.”

The team used publicly available participatory science data for 10,998 populations, belonging to 2684 species, to provide the most extensive quantification of seasonal distribution patterns of mountain birds to date.

Focusing on elevational gradients as natural replicates across mountain regions worldwide, and using seasonality as a natural experiment, the observed seasonal distribution of mountain birds was compared with computer model predictions based on energy efficiency.

The researchers found more than 30 per cent of the avian populations studied that live year-round on the mountain slopes are altitudinal migrants – defined as having average seasonal altitudes separated by more than 200 metres – confirming altitudinal migration to be a “notable phenomenon globally”.

Among these, only a few populations radically shift their distribution along the elevational gradient, for example by more than 1000 metres on average, mirroring the pattern observed for latitudinal migration, where few avian species migrate very long distances.

Altitudinal migration was found to be widespread – in 339 of 1852 populations – within the equatorial tropics despite minimal seasonal temperature changes in these regions.

However, the proportion of altitudinal migrants in a mountain region nonetheless increases with latitude, for example the further north of the equator that populations are, with the tropical Southern Ghats of India having approximately 20 per cent of bird species as altitudinal migrants, while the temperate Swiss Alps have about 57 per cent.

Located in subtropical mid-latitude, eastern Taiwan has approximately 43 per cent of bird species that are altitudinal migrants, such as the Taiwan Yuhina. Overall, this latitudinal pattern supports the idea that altitudinal migration is an adaptation to seasonality.

“Overall, our results suggest that the seasonal distribution of birds in mountains is largely shaped by a complex interplay between species minimising energy costs while maximizing energy acquisition and considering what competitors are doing,” said Dr Somveille.

“Also, that altitudinal migration is a behavioural mechanism allowing birds to optimise their energy budgets in the face of seasonality and competition. This explains the many populations that appear to engage in upslope migration during the colder season, as a distributional strategy that is energetically efficient for some species given the dynamics of competition for access to food.”

Dr Somveille, who started the research while at University College London, collaborated with scientists from the Georgia Institute of Technology and Yale University in the US, and Academia Sinica in Taiwan. It was supported by funding from the Wolfson Foundation and Royal Society.

Journal Reference:

Marius Somveille, Benjamin G. Freeman, Frank A. La Sorte, and Mao-Ning Tuanmu, ‘Climate, ecological dynamics, and the seasonal distribution of birds in mountains’, Science Advances 12, (6): eadz5547 (2026). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adz5547

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of East Anglia (UEA)

Featured image credit: Freepik (AI Gen.)