Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press roundup (February 19, 2026), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

— Press Release —

Can Europe be climate-neutral by 2050? New monitor tracks the pace of the energy transition

The EU is expected to achieve climate neutrality by 2050. How far along is it? “At its core, we simply don’t know. We have a good picture of the supply side – how quickly wind turbines are being erected, grids expanded, and storage capacity increased. But there are no official figures on how fast industry and firms are retrofitting, replacing their machinery, and electrifying their processes,” says CSH President Stefan Thurner.

Together with his team, he has now developed such a monitor. “By drawing on the energy consumption of nearly all relevant companies in a country – in this case Hungary, where these companies account for 75% of all firms’ gas consumption, 70% of electricity consumption, and 50% of oil consumption – we were able, for the first time, to develop an objective method to measure and monitor the state of the energy transition,” says Thurner.

Energy transition barely taking hold at firm level

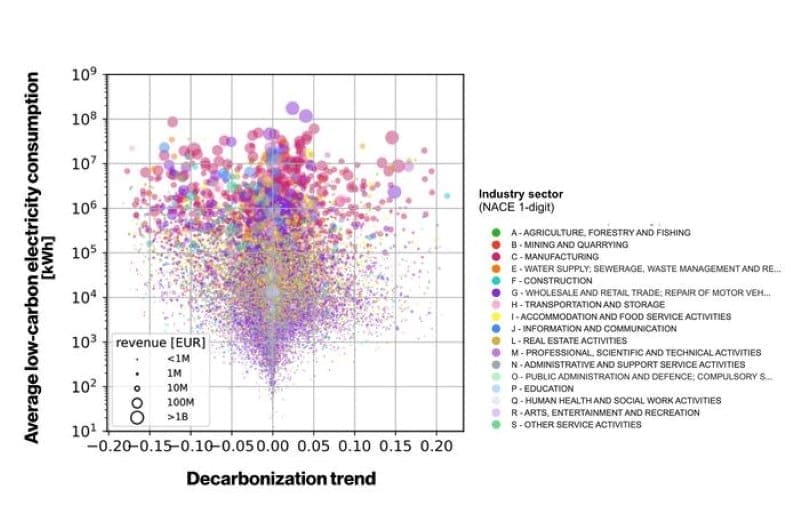

The study, published in Nature Communications, shows that roughly half of the companies increased their share of low-carbon electricity from 2020 to 2024. The other half, however, showed a negative trend and continued to rely on fossil fuels. “It’s not the case that all companies are steadily increasing their share of renewable electricity. We were surprised by how large the share of companies is that are doubling down on gas and oil,” says study author Johannes Stangl of the CSH. “The energy transition is practically not happening in the Hungarian economy,” Thurner emphasizes.

Which companies are switching to electricity?

“What’s striking is that in nearly every subsector, there are companies that consume mostly low-carbon electricity, and others that consume almost none,” says Thurner, which suggests there is no fundamental technical barrier preventing entire industries from making the switch. So why do some companies switch and others do not?

The study found that companies spending a relatively large share of their revenue on fossil fuels are significantly less likely to switch to electricity. Conversely, the higher a company’s electricity costs as a proportion of revenue, the more likely it is to continue investing in electrification.

The researchers point to a possible lock-in effect where companies could find it difficult to move away from their current technologies because switching costs are too high or the investment is too risky. “This finding underscores how important it is to support companies with their initial investments while simultaneously setting a clear climate policy direction. In this way can companies gain the planning certainty needed to be confident that investments in climate-friendly technologies will pay off,” Stangl emphasizes.

Size also plays a role: smaller companies – measured by total energy consumption – are less likely to make the switch, while larger companies, those that consume more energy overall, tend to be more inclined to increase their share of electricity.

Future scenarios

Additionally, the researchers conducted a thought experiment: what if companies with a negative trend (those whose fossil fuel share has remained flat or increased since 2020) were to behave by 2050 the way comparable companies in the same subsector with a positive trend already do? In that scenario, the share of fossil energy could fall to between 30 and 45 percent by 2050; correspondingly, up to 70 percent of energy consumption could come from low-carbon sources.

If, on the other hand, everything stays as it is and companies continue on their current path, the fossil fuel share of companies would still stand at around 80 percent in 2050.

A monitor for as many countries as possible

For their calculations, the researchers reconstructed the energy consumption of over 25,000 Hungarian companies between 2020 and 2024. “It would be enormously important to have this kind of insight in as many countries as possible. That way, one could see how well the energy transition is actually progressing at the firm-level and intervene early where needed, so that the 2050 climate target remains achievable,” says Stangl. So far, however, this is possible primarily in countries where VAT data for every transaction is recorded automatically – such as Hungary, Belgium, Spain, Portugal, and Ecuador, for example.

“While a causal relationship cannot be established with certainty, the statistical associations are so clear and consistent across different sectors that they do point to which factors drive or hinder the switch to electricity in companies,” says Thurner.

“Since electricity from renewable sources is already cheaper today than fossil-based electricity, the power sector will be largely decarbonized within the foreseeable future. What matters, then, is which companies manage to shift their processes to electricity in time, and which continue to cling to fossil fuel technologies,” Stangl states.

“Our findings show that the energy transition in an EU country is currently barely happening – but they also show where potential levers exist,” says Thurner. “If the EU is to meet its 2050 targets, we need a company-level monitor for every EU country, so support can be provided when and where it is needed in a targeted way.”

Journal Reference:

Stangl, J., Borsos, A. & Thurner, S., ‘Using firm-level supply chain networks to measure the speed of the energy transition’, Nature Communications (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-026-69358-4

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Complexity Science Hub (CSH)

— Press Release —

Debilitating virus can spread in cool weather, increasing health risk in Europe

Chikungunya virus, a debilitating tropical disease caused by infected mosquito bites, poses a greater health threat in Europe than previously thought because it can be spread when air temperatures are as low as 13 degrees Celsius.

That is the finding of researchers at the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology who have investigated the ability of the Asian tiger mosquito to spread the virus, which is rarely fatal but can cause long-term chronic joint pain.

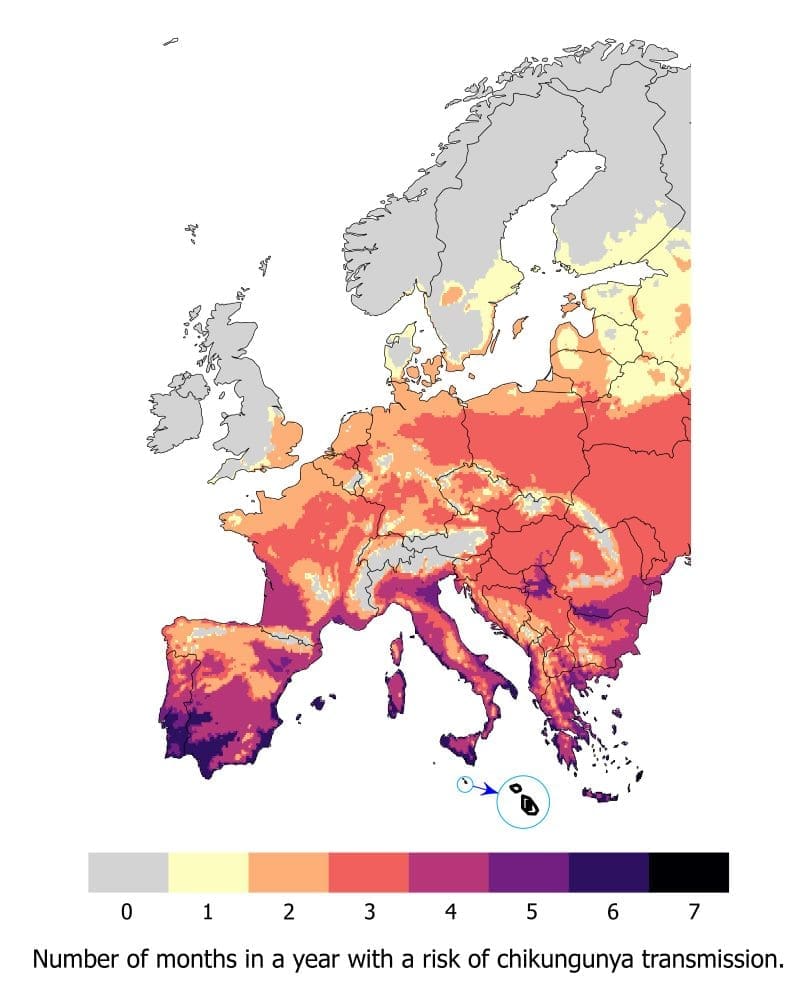

They have drawn up a map showing the extent of the risk of chikungunya for 10km square areas across Europe including the UK. The risk map shows the threat of virus transmission may last several months of the year in warmer parts of the continent where the tiger mosquito is already established.

There were record numbers of local outbreaks of chikungunya in France and Italy in 2025, and the tiger mosquito has also been responsible for increasing numbers of cases of dengue fever in these countries in recent years. This mosquito species is only occasionally detected in south-east England and is not yet established so the current risk of local transmission in the UK remains very low.

Longer period of risk

But the researchers warn that warming temperatures could result in the tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) becoming established in the UK in coming years, posing a disease risk, particularly in south-east England.

Their new study found that the virus can be spread in temperatures of just 13-14 degrees Celsius, while previous research indicated a minimum of 16-18 degrees Celsius. This means there is a risk of local outbreaks of chikungunya in more areas and for longer periods than previously thought.

Sandeep Tegar, an epidemiological modeller at UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (UKCEH), led the study which has been published in the Journal of Royal Society Interface. He said: “Europe is warming rapidly, and the tiger mosquito is gradually expanding northwards through the continent. The lower temperature threshold that we have identified will therefore result in more areas – and more months of the year – becoming potentially suitable for transmission.

“Identifying specific locations and the months of possible transmission will enable local authorities to decide when and where to take action to reduce the risk, or scale, of outbreaks. Our research could also help predict how climate change could influence the future spread of the chikungunya virus.”

Climate change impacts

Global transport results in the increased spread of non-native species to new regions while warmer temperatures create more suitable conditions for populations to thrive in new areas. Warmer weather also increases the rate at which viruses replicate in an insect’s body, thereby increasing the risk of transmission.

Tiger mosquitoes that are resident in Europe have bitten returning travellers who have been infected by the virus while abroad and then transmitted it to other people in the area, starting a local outbreak.

The UKCEH risk map shows the possibility of transmission lasts two-three months in summer across much of the continent and four-six months in southern and eastern Spain and Portugal, with a high risk in Malta from March-November.

Long-term threat to UK

For the UK, the map shows that there is currently a low risk in East Anglia and the south-eastern corner of England during July and August, and for one of these months in pockets elsewhere in the south. There have not yet been any local transmissions of chikungunya in the UK but there were a record 73 travel-related cases – i.e. among people who contracted the virus abroad – between January and June 2025, compared to 27 cases in the same period in 2024.

However, looking ahead, the study authors warn that rising temperatures will increase the odds of the tiger mosquito establishing in the UK, as has happened elsewhere in Europe. The risk of chikungunya could therefore increase beyond July and August, and to other areas of the country.

“Existing maps do not highlight these UK risk zones,” said study senior author Dr Steven White of UKCEH.

“It is important that there is continued action to try to prevent the tiger mosquito from establishing in this country because this highly invasive species is capable of transmitting several infections that can cause serious health conditions including chikungunya, dengue and Zika viruses.”

Continued vigilance

The UK Health Security Agency coordinates a national surveillance programme including the use of traps to detect any incursions of the tiger mosquito into the UK, focusing on airports, ferry terminals, distribution centres and service stations.

Measures to reduce the risk of outbreaks and cases where virus-carrying mosquitoes are present in an area include:

- Carrying out surveillance of potential mosquito breeding areas, such as stagnant water, or removing these possible habitats.

- Fumigation of these areas as well as open spaces and the homes of infected people.

- Targeting health resources to high-risk areas such as issuing vaccines.

- Issuing advice to the public on preventing being bitten.

UKCEH also recently produced a Europe-wide risk map for dengue fever, predicting hotspots, and is planning similar exercises for Zika and West Nile viruses.

Journal Reference:

Sandeep Tegar, Dominic P. Brass, Bethan V. Purse, Christina A. Cobbold, Steven M. White, ‘Temperature-sensitive incubation, transmissibility and risk of Aedes albopictus-borne chikungunya virus in Europe’, Journal of The Royal Society Interface 23 (235): 20250707 (2026). DOI: 10.1098/rsif.2025.0707

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (UKCEH)

— Press Release —

What freezing plants in blocks of ice can tell us about the future of Svalbard’s plant communities

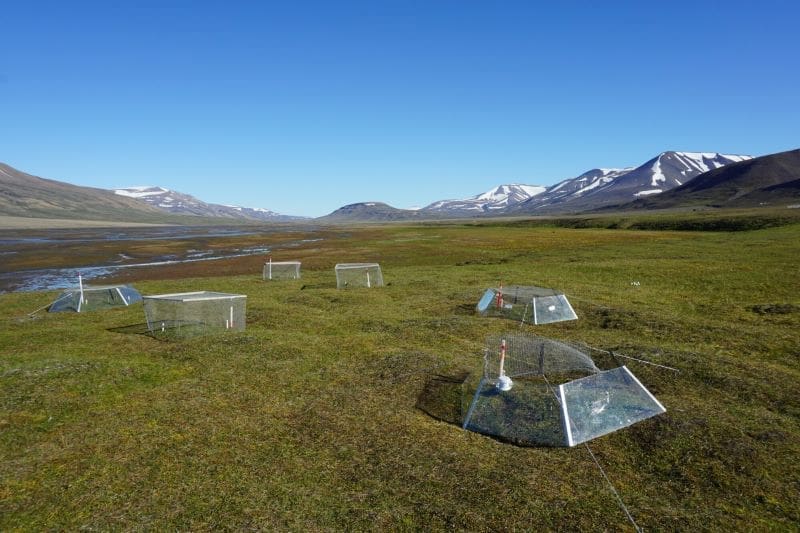

For five Januarys starting in 2016, researchers and students from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) travelled to a small valley outside of Svalbard’s main city with big jugs of liquid water and an unusual goal: To encase selected plant plots in a thick cover of ice.

Their focus was a plant community dominated by the polar willow, a critical year-round food for Svalbard’s reindeer population.

They wanted to see what happens to these plant communities during winter weather extremes, where prolonged rain instead of snow can freeze the ground solid and encase plants in a thick icy cap – right until spring melt.

But to make the experiment truly reflect what will happen as the Arctic warms, some plant plots during the summer were encased in little open-top plexiglass greenhouses.

The greenhouses made the plots warmer than the environment around them, simulating the higher temperatures that are expected on Svalbard as the Arctic continues to warm.

You might think that being frozen in a block of ice followed by being warmed in the little greenhouses might mean the end for these plants.

But much to their surprise, the researchers found quite the opposite effect.

Summer warming counteracts effects of winter icing

“If you sum up what happened throughout the entire growing season, you actually had more above-ground production (in the frozen and then warmed plants) than plants in the control situation,” said Mathilde Le Moullec, a researcher at the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources and at NTNU.

She was the first author of a paper about their findings, just published in the Journal of Ecology.

So what does that actually mean?

Biologists here use the word production to describe everything a plant produces above-ground during the summer growing season, from leaves and branches, to flowers and seeds.

More production generally means that the plant is stronger, can make more reserves to survive another winter, expand the amount of ground it covers and produce offspring.

In this case, the plants that got encased in a thick covering of ice, along with extra warming in the summer – were the winners.

“More above-ground production also means more forage for reindeer in summer and fall, allowing them in turn to build up reserves to survive the winter. This also matters because winter ice can possibly encase these plants, which can make them inaccessible to reindeer,” said Brage Bremset Hansen, a professor at NTNU’s Gjærevoll Centre and a senior researcher at Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA).

Timing important, too

But what about timing – when plants produced their leaves, flowers and seeds?

Timing matters because Arctic summers are so short, flowers and seeds that are produced too late in the summer will not help the plant reproduce. Here, the findings were mixed.

The polar willows that had only been encased in ice were delayed in opening their leaves, because it took longer to thaw the soil. But they eventually sped up their development. Nevertheless, they had smaller and thinner leaves than the control plants.

The plants that had only been frozen also didn’t make as many flowers and were late with making seeds.

But the plants that had been frozen and then warmed – they were supercharged. Their production exceeded and was earlier than the controls. Their seed dispersal was also advanced, even more than the plants that weren’t subjected to freezing and were only warmed in the little greenhouses.

The main drawback, it seemed, for all the plants other than the controls was that they produced fewer flowers.

However, Arctic plants mainly reproduce asexually, through cloning or expanding rhizomes, so less flower production may not be that critical, as long as a few seeds survive and are dispersed at the right time, Le Moullec said.

Five years of consistent freezing

Researchers try to design experiments out in the field that mimic as closely as they can the environmental changes they’re trying to understand.

In this case, Le Moullec and her colleagues had to think carefully about the 50 x 50 cm plots that they planned to freeze. They had to hold the water in place as it froze somehow. In the end, they decided to surround the plots with 60 x 60 cm frames.

In real life, however, the layer of ice might be much more extensive than that and cover an entire valley. And the researchers knew that sometimes the ice could be much thicker than the 13 cm thickness they used.

That matters because plants do actually “breathe” – not like humans, of course, but they take in CO₂ and release oxygen in the process of photosynthesis. In winter when there is no light and they’re not photosynthesizing, they need oxygen to maintain their cells in a healthy state. So if they’re frozen in an extensive layer of ice, they might be at risk of anoxia – suffocating.

Nevertheless, after five years of consistent freezing, they didn’t encounter this problem.

“Over the five years, we don’t see any accumulated effect, which means that the community is actually very resilient to icing,” Le Moullec said. “And when you see what we do to them, that’s a surprise.”

More to learn about a surprisingly resilient system

This is now the 11th year where researchers have visited Adventdalen in the winter with big jugs of water to simulate the effects of winter rain and frozen soil on Svalbard plants. Hansen says the plan is to continue to return to the plots and redo the measurements. The goal is to better understand potential long-term effects of a warmer Arctic on these plant communities.

Even as the Arctic warms, it remains an unforgiving environment for plants and animals alike.

“Arctic vegetation communities are exposed to a huge amount of variability, with lots of changes in when the spring onset is, and with winter conditions,” Le Moullec said.

The polar willow community, however, “ is a surprisingly resilient system,” she said.

Journal Reference:

Le Moullec, M., Hendel, A.-L., Petit Bon, M., Jónsdóttir, I. S., Varpe, Ø., van der Wal, R., Beumer, L. T., Layton-Matthews, K., Isaksen, K., & Hansen, B. B., ‘Towards rainy high Arctic winters: How experimental icing and summer warming affect tundra plant phenology, productivity and reproduction’, Journal of Ecology 114, (1): e70234 (2026). DOI: 10.1111/1365-2745.70234

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Nancy Bazilchuk | Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU)

Featured image credit: Freepik (AI Gen.)