Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press roundup (December 28, 2025), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

Japanese eels, climate change, and river temperature

The distribution of Japanese eels (Anguilla japonica) at the northern edge of the species’ range appears to be shaped by river water temperature, which is influenced by watershed geology and land use. Osamu Kishida and colleagues conducted electrofishing surveys in 105 rivers across southern Hokkaido, Japan, capturing 222 Japanese eels from 52 rivers.

The authors used structural equation modeling that incorporated catch per unit effort, environmental variables, and estimates of glass eel recruitment – the number of juvenile eels that enter rivers from the sea, where they are born – based on an ocean circulation model. The analysis showed that eels were more abundant in rivers with higher summer water temperatures.

Rivers with watersheds dominated by farmland and urban areas tended to have warmer summer temperatures, while rivers in watersheds with volcanic geology, particularly younger volcanic formations, had cooler summer temperatures. The volcanic geology’s high permeability allows rapid infiltration of precipitation, resulting in spring-fed rivers that remain cooler in summer.

According to the authors, global warming combined with urbanization may facilitate northward expansion of Japanese eel populations, though expansion in this region may be constrained by past volcanic activity that shapes the thermal environment of rivers.

Journal Reference:

Kanta Muramatsu, Mari Kuroki, Yu-Lin K Chang, Kentaro Morita, Osamu Kishida, ‘Thermal constraints on the distribution of Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica) at its northern limit: Links to land use and geology’, PNAS Nexus 4, 12: pgaf384 (2025). DOI: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgaf384

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by PNAS Nexus

Construction secrets of honeybees: Study reveals how bees build hives in tricky spots

On a hot summer day in Colorado, European honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) buzz around a cluster of hives near Boulder Creek. Worker bees taking off in search of water, nectar and pollen mingle with bees that have just returned from the field. Inside the hives, walls of hexagons are beginning to take shape as the bees build their nests.

“Building a hive is a beautiful example of honeybees solving a problem collectively,” said Orit Peleg, associate professor in CU Boulder’s Department of Computer Science. “Each bee has a little bit of wax, and each bee knows where to deposit it, but we know very little about how they make these decisions.”

In an August 2025 study in PLOS Biology, Peleg’s research group collaborated with Francisco López Jiménez, associate professor in CU’s Ann and H.J. Smead Department of Aerospace Engineering Sciences, and his group to offer new insight into how bees work their hive-making magic – even in the most challenging of building sites.

The new findings could spark ideas for new bio-inspired structures or even new ways to approach 3D printing.

How and why bees build honeycomb

Honeybees can build nests in any number of places, whether it’s a manmade box, a hole in a tree trunk or an empty space inside someone’s attic. When a bee colony finds somewhere new to call home, the bees build their hive out of honeycomb – a waxy structure filled with hexagonal cells – on whatever surfaces are around.

Building a beehive is hard work, and it consumes a lot of resources. It all starts with honey, the nutrient-dense superfood that helps bee colonies survive the winter.

To make honey, bees spend the warmest months gathering nectar from flowers. The nectar mixes with enzymes in the bees’ saliva, and the bees store it in honeycomb cells until it dries and thickens.

It takes roughly 2 million visits to flowers for bees to gather enough nectar to make a pound of honey. Then, each worker bee must eat about 8 ounces of honey to produce a single ounce of the wax they need to build more honeycomb.

If the surface of their building site is irregular, the bees have to expend even more resources building it, and the resulting comb can be harder to use. So efficiency is key.

In an ideal world, bees try to build honeycomb with nearly perfect hexagonal cells that they use for storing food and raising young larvae into adults. Mathematically, the hexagonal shape is ideal for using as little wax as possible to create as much storage space as possible in each cell.

The honeycomb cells are usually a consistent size, but when bees are forced to build comb on odd surfaces, they start making irregular cells that take more wax to build and aren’t as optimal for storage or brood rearing.

Irregular surfaces: A puzzle for bees to solve

Golnar Gharooni Fard, the lead author of the new study and a former CU graduate student, said her main goal in the study was to understand how bees work together to solve the structural problems they might run into.

“We wanted to find the rules of decision-making in a distributed colony,” Fard said.

The researchers 3D printed panels, or foundations, for bees to build comb on. The team imprinted the foundations with shallow hexagonal patterns with differing cell sizes – some larger, some smaller, and some closer to an average cell size – and added the foundations to hives for the bees to use.

Next, the researchers used X-ray microscopy to analyze patterns in the comb the bees built on each type of foundation. Depending on which foundation they were given, the bees used strategies like merging cells together, tilting the cells at an angle or layering them on top of one another to build usable honeycomb.

Giving bees these different surfaces to work with was like giving them puzzles they had to solve, said López Jiménez.

“All those things happen in nature. If they’re building honeycomb on a tree, and at some point they get to the end of the branch, the branch might not be super flat, and they need to figure that out,” he said.

It’s still not clear why bees use the strategies they use in all situations. That’s a question the researchers hope to continue exploring.

Meanwhile, the team sees numerous possible applications for their findings. For example, honeycomb could inspire designs for efficient, lightweight structures such as those used in aerospace engineering.

López Jiménez also likened the honeycomb building process to 3D printing, where each bee gradually adds tiny bits of wax to the larger structure.

“The bees take turns, and they organize themselves, and we don’t know how that happens,” he said. “Can we learn from how the bees organize labor or how they distribute themselves?”

***

CU graduate student Chethan Kavaraganahalli Prasanna was also part of the research team.

Journal Reference:

Gharooni-Fard G, Kavaraganahalli Prasanna C, Peleg O, López Jiménez F, ‘Honeybees adapt to a range of comb cell sizes by merging, tilting, and layering their construction’, PLoS Biology 23 (8): e3003253 (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3003253

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Amber Carlson, Nicholas Goda | University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder)

On an iconic Colorado 14er, climate change is shifting the timing between flowers and pollinators

Warming temperatures and earlier snowmelt are disrupting the long-running relationship between wildflowers and their pollinators on Colorado’s Pikes Peak.

In a new study published in The American Naturalist, researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder found many of the region’s plants and pollinators are now emerging earlier in the spring than they did a century ago. But some species are falling out of sync, potentially adding challenges for pollinators already under threat.

“Pollinators are so important to our ecosystem, supporting everything from wildflowers to the food we eat,” said Julian Resasco, the paper’s senior author and associate professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. “Having data from 100 years ago gave us a unique opportunity to take a glimpse of these long-term trends under a changing climate.”

Starting in 1910, ecologist Frederic Clements and his student Frances Long began documenting the interactions between local plants and their pollinators at the now-closed Carnegie Institution’s Alpine Laboratory on the slope of the 14,115-foot Pikes Peak near Colorado Springs.

Over the past century, Colorado has warmed by an average of 2.9 °F (1.61 °C), with the average winter temperature rising even faster, by 3.3 °F (1.83 °C). Climate change has also decreased the amount of snow accumulating on top of the mountains, or snowpack, in the western United States, reducing the amount of water available for mountain species in spring and summer.

Warming temperature and snowmelt are vital environmental cues for plants and insects to emerge from their winter inactive state.

As the climate warms and snow melts earlier, plants may begin flowering sooner and pollinators may start flying earlier. But not all species respond to it in the same way or at the same pace, said Leana Zoller, the paper’s first author and a former postdoctoral associate at CU Boulder.

Resasco, Zoller and their team returned to Clements and Long’s study area to see if the interactions between plants and pollinators have shifted over the past century. Because Pikes Peak is a protected wilderness area, its environment has remained largely undisturbed. This allowed the team to study the impact of climate change without other influences such as land use change.

Between 2019 and 2022, the research team analyzed 25 wild pollinator species, including bumblebees, wasps and flies, as well as 11 flowering plants the insects interact with, forming 149 pairs of interactions.

Of the species that could be compared between the historical and contemporary datasets, they found that wildflowers were blooming about 17 days sooner than a century ago, and pollinators started to fly 11 days earlier.

Out of the 149 pairs of plant-pollinator comparable interactions, nearly 80% have more overlap in their active periods than before. While this trend appears beneficial for pollinators now, the advantage may be short-lived.

Historically, pollinators were active earlier than plants started flowering. “In our study system plants have advanced more rapidly than pollinators. If the trends continue, we may see plants flower before pollinators become active in the future,” said Zoller, who is currently a postdoctoral associate at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

“Mismatches may occur among these currently overlapping pairs as plants and pollinators continue to respond differently to changing conditions,” she added.

Some species are already slipping out of sync.

The western bumblebee, for example, is emerging 12 days later than a century ago, which could leave it struggling to find enough food. Once common and widespread in the western United States and Canada, this species has sharply declined by at least 57% since 1998 due to a mix of disease, habitat loss and pesticides.

“This mismatch in the schedules of western bumblebees and the plants they historically fed on could add another stressor on top of everything else this species is facing,” Resasco said.

Pollinators, including domestic honeybees and wild species, contribute to the reproduction of 75% of the world’s flowering plants and about 35% of the world’s food crops. Their decline could have far-reaching effects on both natural landscapes and agriculture.

“Wild pollinators help maintain the biodiversity of plants in our ecosystems. We have a responsibility to make sure they don’t disappear,” Resasco said.

Journal Reference:

Leana Zoller, Diego P. Vázquez, and Julian Resasco, ‘Phenological Shifts in Plants and Pollinators over a Century Disrupt Interaction Persistence’, The American Naturalist 207, 1 (2026). DOI: 10.1086/738351

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder)

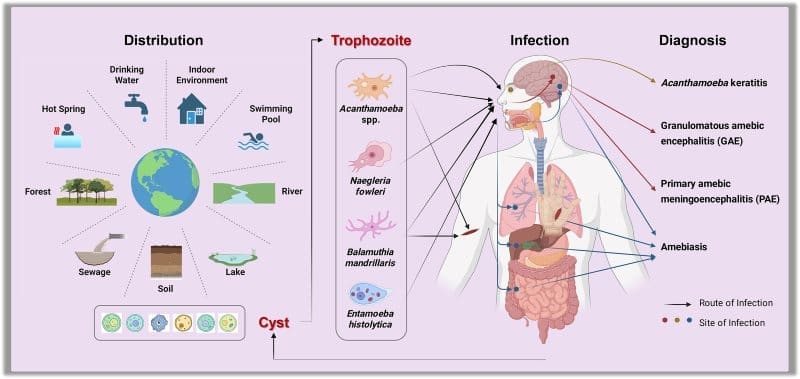

Invisible but deadly: Scientists warn of a growing global threat from amoebae in water and the environment

A group of environmental and public health scientists is sounding the alarm on a largely overlooked but increasingly dangerous group of pathogens: free living amoebae. In a new Perspective article published in Biocontaminant, the researchers highlight how these microscopic organisms are becoming a growing global public health threat, fueled by climate change, aging water infrastructure, and gaps in monitoring and detection.

Amoebae are single celled organisms commonly found in soil and water. While most are harmless, some species can cause devastating infections. Among the most notorious is Naegleria fowleri, often referred to as the brain eating amoeba, which can trigger a rare but almost always fatal brain infection after contaminated water enters the nose during activities such as swimming.

“What makes these organisms particularly dangerous is their ability to survive conditions that kill many other microbes,” said corresponding author Longfei Shu of Sun Yat sen University. “They can tolerate high temperatures, strong disinfectants like chlorine, and even live inside water distribution systems that people assume are safe.”

The authors also emphasize that amoebae act as hidden carriers for other harmful microbes. By sheltering bacteria and viruses inside their cells, amoebae can protect these pathogens from disinfection and help them persist and spread in drinking water systems. This so called Trojan horse effect may also contribute to the spread of antibiotic resistance.

Climate warming is expected to worsen the problem by expanding the geographic range of heat loving amoebae into regions where they were previously rare. Recent outbreaks linked to recreational water use have already raised public concern in several countries.

The researchers call for a coordinated One Health approach that connects human health, environmental science, and water management. They urge stronger surveillance, improved diagnostic tools, and the adoption of advanced water treatment technologies to reduce risks before infections occur.

“Amoebae are not just a medical issue or an environmental issue,” Shu said. “They sit at the intersection of both, and addressing them requires integrated solutions that protect public health at its source.”

Journal Reference:

Zheng J, Hu R, Shi Y, He Z, Shu L., ‘The rising threat of amoebae: a global public health challenge’, Biocontaminant 1: e015 (2025). DOI: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0019

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Biochar Editorial Office | Shenyang Agricultural University

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay