Summary:

Melting glaciers may release hidden antibiotic resistance into some of the world’s most important freshwater systems, according to a new review published in Biocontaminant. As climate change accelerates glacier loss, scientists are examining how long-preserved antibiotic resistance genes, or ARGs, stored in ice are being mobilised into rivers and lakes downstream.

The review explains that glaciers function as natural archives, preserving microbial communities and genetic material for thousands to hundreds of thousands of years. While antibiotic resistance is often associated with modern medicine, many resistance genes are ancient and naturally occurring. Once released through meltwater, these genes can enter glacier-fed rivers and lakes that provide drinking water and support ecosystems in polar and high-altitude regions.

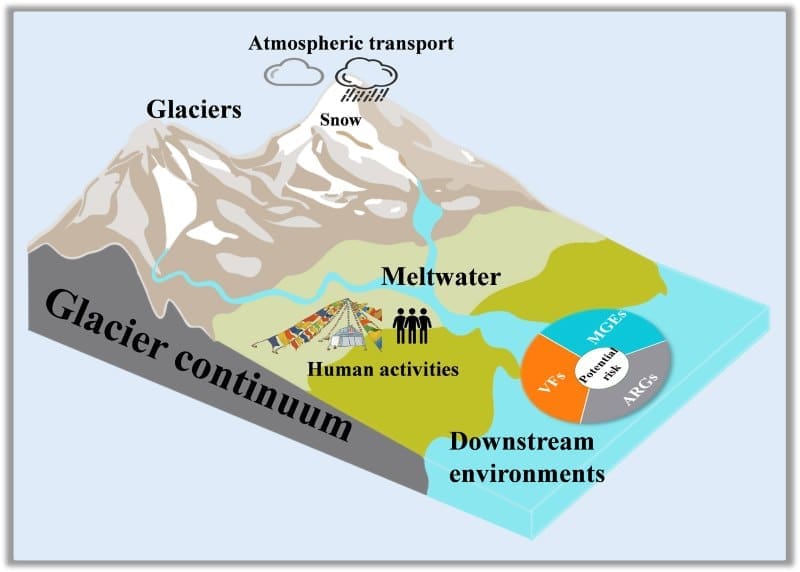

Drawing on studies from Antarctica, the Arctic, and the Tibetan Plateau, the authors show that glaciers generally contain lower resistance levels than polluted environments but still harbour a wide range of ARGs, including those linked to clinically important antibiotics. The review introduces the concept of a “glacier continuum,” emphasising that glaciers, streams, and downstream lakes operate as a connected system where resistance genes can be transported, transformed, and potentially amplified. The authors argue that understanding this continuum is essential for assessing ecological and public health risks in a warming climate.

Melting glaciers may release hidden antibiotic resistance into vital water sources

In a new review in Biocontaminant, researchers report that glaciers act as long-term reservoirs of antibiotic resistance genes, or ARGs, genetic elements that allow bacteria to survive exposure to antibiotics. Once released by glacier melt, these genes can enter rivers, lakes, and ecosystems that supply drinking water and support wildlife in polar and high-altitude regions.

“Glaciers have long been viewed as pristine and isolated environments,” said corresponding author Guannan Mao of Lanzhou University. “Our review shows that they are also genetic archives that store antibiotic resistance, and climate-driven melting is turning these archives into active sources.”

Antibiotic resistance is one of the most pressing global public health challenges. While resistance is often linked to modern antibiotic use, many resistance genes are ancient and naturally occurring. Glaciers preserve microorganisms and their DNA under cold, low-nutrient conditions, sometimes for hundreds of thousands of years. As temperatures rise, these preserved microbes and genes are being released into downstream freshwater systems.

The authors synthesized findings from studies across Antarctica, the Arctic, the Tibetan Plateau, and other glacier regions. Although resistance levels in glaciers are generally lower than in heavily polluted environments, the review shows that a wide variety of resistance genes have been detected, including those linked to clinically important antibiotics.

“Glacier-fed rivers and lakes are essential water sources for millions of people,” Mao said. “Once resistance genes enter these connected systems, they can interact with modern bacteria, increasing the risk of spread through microbial communities.”

A key contribution of the study is the introduction of the “glacier continuum” concept. Rather than treating glaciers, rivers, and lakes as separate environments, the researchers argue they should be understood as a connected system through which resistance genes are transported, transformed, and potentially amplified.

As meltwater flows downstream, environmental conditions become more favorable for microbial growth and gene exchange. Rivers can act as mixing zones where resistance genes move between bacteria, while lakes may accumulate these genes and pass them through food webs, including into fish and other aquatic organisms.

“Most previous studies have looked at individual habitats in isolation,” said Mao. “That approach misses how resistance genes actually move through real landscapes. The glacier continuum allows us to understand where risks may increase and where intervention or monitoring is most needed.”

The review also highlights growing evidence that resistance genes can coexist with virulence factors, genetic traits that enable bacteria to cause disease. This combination raises concerns that glacier melt could contribute to the emergence of bacteria that are both drug resistant and potentially harmful.

Human activities further complicate the picture. Airborne pollutants, migratory birds, tourism, and scientific stations can introduce modern resistance genes into remote glacier environments. In some regions, such as the Arctic, resistance levels are significantly higher than in Antarctica, reflecting stronger human influence.

To address these risks, the authors call for coordinated monitoring programs using advanced genetic tools, such as metagenomic sequencing, to track resistance genes along the glacier continuum. They also emphasize the need for early-warning frameworks that assess ecological and health risks before resistance spreads widely.

“Climate change is reshaping microbial risks in ways we are only beginning to understand,” Mao said. “Recognizing glaciers as part of the global antibiotic resistance landscape is an important step toward protecting both environmental and human health.”

The findings underscore the importance of viewing antibiotic resistance through a One Health lens that connects environmental change, ecosystem integrity, and public health in a warming world.

Journal Reference:

Ying H, Zhang Y, Hu W, Wu W, Mao G., ‘Glaciers as reservoirs of antibiotic resistance genes: hidden risks to human and ecosystem health in a warming world’, Biocontaminant 1: e021 (2025). DOI: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0022

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Biochar Editorial Office | Shenyang Agricultural University

Featured image credit: Tobias Waibl | Pexels