Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press daily roundup (August 12, 2025), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

Rising carbon dioxide level disrupts insects’ ability to choose optimal egg-laying sites

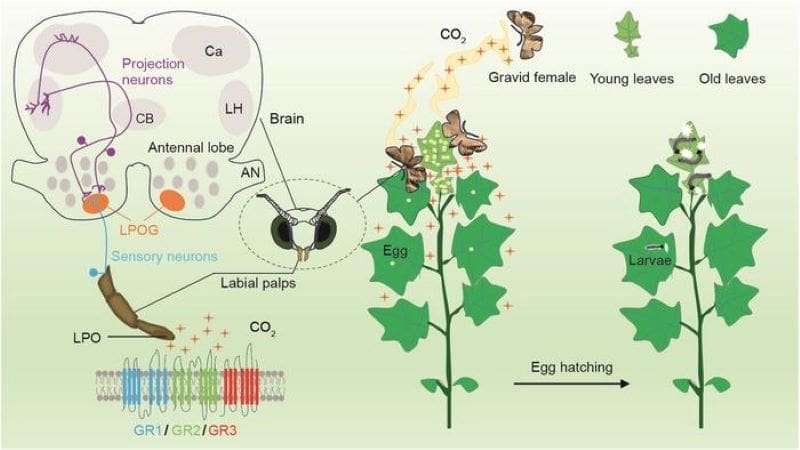

Climate change is rapidly reshaping ecosystems across the globe, and new research has identified a previously unrecognized consequence: disrupted insect reproductive behavior. A recent study published in National Science Review reveals that rising atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO₂) levels are interfering with how agricultural pests choose egg-laying sites – posing significant risks to biodiversity, food security, and pest management strategies.

Insects, despite their adaptability, are especially sensitive to shifts in environmental conditions. As global temperatures rise and atmospheric composition changes, their behavior is changing in ways that ripple through ecosystems. CO₂, the primary greenhouse gas driving global warming, has increased from 278 ppm in 1750 to approximately 420 ppm in 2023. Emerging evidence shows that elevated CO₂ levels – alongside pollutants such as ozone and nitrogen oxides – are disrupting insects’ ability to detect chemical cues essential for reproduction and survival. Until now, the underlying mechanisms remained poorly understood.

Now, an international collaborative study by scientists from the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, and the Max Planck Institute has provided key insights. Focusing on Helicoverpa armigera – the cotton bollworm, a major global crop pest – the team discovered that females normally use plant-emitted CO₂ to locate suitable egg-laying sites, particularly favoring younger leaves that emit higher CO₂ gradients.

These sites are critical for larval survival and development. However, under elevated atmospheric CO₂ concentrations, this behavior is significantly disrupted. The study found that moths’ CO₂-sensing ability is impaired, causing them to lay eggs in less suitable locations. “This disruption is akin to confusing a key olfactory cue from a GPS system,” said Prof. Guirong Wang, lead author of the study. “Without accurate CO₂ signals, the insects struggle to find ideal egg-laying sites, which could affect pest population dynamics and agricultural damage.”

To understand the biological basis for this disruption, the researchers identified three CO₂-detecting gustatory receptors – HarmGR1, HarmGR2, and HarmGR3. When any of these receptors were genetically deleted, the moths’ ability to detect CO₂ impaired, resulting in disoriented egg-laying behavior.

The study’s simulations paint a worrying future: if atmospheric CO₂ reaches 1000 ppm by 2100, moths’ preference for optimal egg-laying sites could drop by up to 75%. This would likely reduce larval survival, destabilize pest populations, and alter biodiversity and ecological balance.

Beyond the alarming ecological implications, these findings point to new opportunities. “By targeting the CO₂ receptors, we can explore novel, eco-friendly pest control strategies,” said Dr. Qiuyan Cheng, first author of the paper. One promising approach is RNA interference (RNAi), a gene-silencing technique already used in mosquito control, which could disrupt pest reproduction without harmful chemicals.

The study adds to growing evidence that climate change is influencing insect behavior in complex and unexpected ways – not only through temperature shifts but also via direct changes to atmospheric chemistry. With global CO₂ levels on track to exceed 1000 ppm by the end of the century, researchers stress the urgent need for both emissions reductions and innovative agricultural adaptation.

Journal Reference:

Qiuyan Chen, Hetan Chang, Baiwei Ma, Mengbo Guo, Song Cao, Bin Li, Xiaoqing Wang, Bente Berg, Xi Chu, Tiantao Zhang, Bill Hansson, Yang Liu, Guirong Wang, ‘Carbon dioxide drives oviposition in Helicoverpa armigera’, National Science Review online, nwaf270 (2025). DOI: 10.1093/nsr/nwaf270

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Science China Press

Why these hairy caterpillars swarm every decade – then vanish without a trace

Western tent caterpillars might not be on your mind every year, but during their peak outbreaks, they’re impossible to ignore – hairy larvae wriggling across roads and swarms of caterpillars climbing houses to form yellow silken cocoons.

They’re certainly on the mind of Dr. Judith Myers, professor emerita in the faculties of science and land and food systems, who has spent five decades studying this native moth species and their boom-and-bust population cycles.

In this Q&A, she discusses her journey and findings from a recently published study, including the caterpillars’ surprising resistance to climate change.

Q: Where are Western tent caterpillars?

A: These hairy, orange-black caterpillars occur across B.C., especially Vancouver Island and the southern Gulf Islands, ranging as far as Manitoba and California. They mostly feed on the leaves of red alder and fruit trees. Eggs hatch in April and the larvae stay together, building a silken ‘tent’ for warmth and shelter, hence their name. In early June, the larvae leave their tents to find vertical surfaces and safer places off the ground to pupate. This can lead to dense clusters on fences, walls, and houses – a sight many people find revolting. After a year or two at high density, population numbers drop and tent caterpillars are temporarily forgotten.

In large numbers, tent caterpillars can defoliate fruit trees. On Salt Spring Island, a severe outbreak in 2012 led to the cancellation of the apple festival. Tourists visiting the Gulf Islands have been known to cut their visit short in response to caterpillar outbreaks. And they’re apparently no good to eat, as they’re thought to have caused severe illness to a horse that accidentally ingested larvae.

What drew you to study these insects for five decades?

I’ve always been interested in what causes animal populations to rise and fall. After I moved to British Columbia in 1972, my interest grew when my husband and I were courting. He worked on Mandarte Island studying song sparrows, and I often joined him on the weekends. While he worked on sparrows, I observed the caterpillars – a fascination from a graduate seminar I gave years earlier. Over time, I became captivated by how their cycles interact with natural controls like viral disease.

What have we learned about these fuzzy critters?

Over the years, myself and other researchers have confirmed that a virus specific to these caterpillars was driving the populations’ cyclicdeclines, something seen in some other moth species as well.

My research partner and SFU professor Dr. Jenny Cory and I observed that outbreaks occur simultaneously across islands and the mainland. We were surprised to find that as populations increase, some female moths must fly tens of kilometres to lay their eggs in areas where populations previously went extinct.

Interestingly, over 50 years, we haven’t seen any effect of global warming on these insect populations. They’re highly adapted to the environment – basking in the sun when it’s cool and sheltering under tents when it’s hot.

Perhaps we humans can learn about our own adaptability from tent caterpillars – are we too defoliating our own “trees” with a booming global population which the Earth can’t support?

When can we expect our hairy overlords to descend again?

The last major outbreak was in 2023 on Galiano and other islands including Westham Island in the lower mainland of BC. This year, we found just one tent in our study area on Galiano. That crash is typical, but tent caterpillars will begin to increase gradually over the next six to eight years to reach another outbreak.

Outbreaks can be predicted, and their damage controlled:

- As numbers begin increasing, we can often forecast an outbreak three years ahead. This is the time to start checking in April for small, hairy larvae and silky tents in fruit trees;

- To protect your backyard, early intervention helps. If you see egg masses in winter or tiny larvae forming tents in spring, you can remove them before they damage trees;

- Commercial fruit growers often use Btk, a safe and effective microbial insecticide. But it works best if applied early, before the caterpillars cause significant damage;

- Remember not to panic: the virus acts as a natural control as the caterpillars become overcrowded.

Journal Reference:

Myers, J. H., & Cory, J. S., ‘Long-term population dynamics of western tent caterpillars: History, trends and causes of cycles’, Journal of Animal Ecology online, 1–13 (2025). DOI: 10.1111/1365-2656.70104

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Ishita Mahajan | University of British Columbia (UBC)

‘Disease detectives’ discover cause of sea star wasting disease that wiped out billions of sea stars

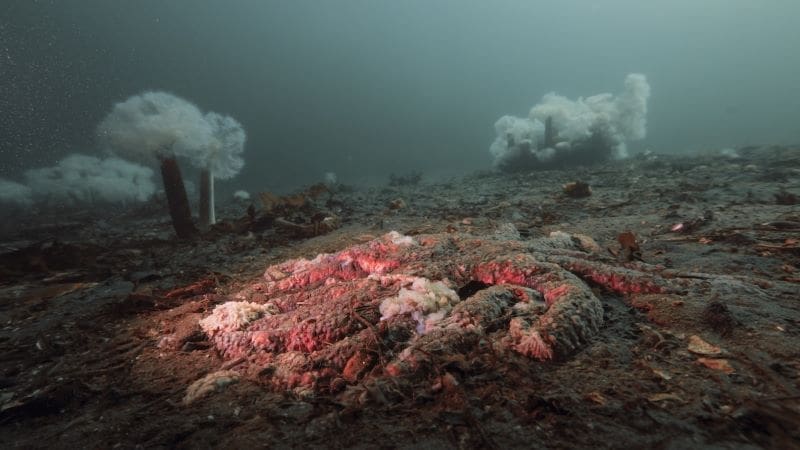

Researchers have identified the cause of the wasting disease that has killed billions of sea stars from Mexico to Alaska since 2013: a strain of the Vibrio pectenicida bacteria.

The strain, named FHCF-3, is detailed in a new paper published in Nature Ecology & Evolution by scientists from University of British Columbia (UBC), the Hakai Institute and the University of Washington.

“Wasting disease is considered the largest ever marine epidemic in the wild, but the definitive cause has remained elusive – until now. Now that we’ve identified the disease-causing agent, we can start looking at how to mitigate the impacts of this epidemic,” said first author Dr. Melanie Prentice, a research associate at UBC’s department of earth, ocean and atmospheric sciences (EOAS) and the Hakai Institute.

The Vibrio genus of bacteria has infected coral and shellfish as well as humans – Vibrio cholerae is the pathogen that causes cholera.

With other Vibrio species known to proliferate in warm water, the race is on to understand the link between the disease and warming ocean temperatures due to climate change, Dr. Prentice added. “We see the disease occurring earlier and more rapidly in warmer waters. Sea stars may already be impacted by climate change, so introducing a pathogen that does well in the same circumstances could be a double whammy for some species.”

The disease begins with lesions and ultimately kills sea stars by “melting” their tissues, a process that takes about two weeks after exposure. Afflicted animals become contorted and lose their arms. But identifying the disease in afflicted sea stars was difficult, as sea stars can respond to other stressors, such as changes in temperature, with similar visual signals of contortion and loss of arms.

Over four years, the international research team investigated sunflower sea stars, which have lost over 90 per cent of their population due to wasting disease. The team compared healthy sea stars with those exposed to the disease through contaminated water, infected tissue or coelomic fluid – sea star “blood.”

“When we looked at the coelomic fluid of exposed and healthy sea stars, there was just one thing different: Vibrio,” said senior author Dr. Alyssa Gehman, an adjunct professor at UBC’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries and a marine disease ecologist at the Hakai Institute. “We all had chills. We thought, ‘That’s it. We have it. That’s what causes wasting.’”

All three methods succeeded in transmitting the disease, with more than 90 per cent of healthy sea stars dying within a week of showing symptoms.

Co-author Amy M. Chan, research scientist at the EOAS marine microbiology and virology laboratory, created pure cultures of V. pectenicida strains including FHCF-3 from the coelomic fluid of sick sea stars. When these FHCF-3 cultures were injected into healthy sea stars, they all died within a few days of showing symptoms, confirming this strain was the cause of the disease.

“Using DNA sequencing, we saw there was a huge signal of a particular bacteria. This was our prime suspect to isolate. When I did, I saw basically only one kind of bacteria growing on the plates and thought, ‘This has got to be it’.”

The loss of billions of sunflower sea stars – a natural predator of sea urchins – has driven widespread, lasting effects on marine ecosystems. “Without sunflower stars, sea urchin populations have increased, devouring the kelp forests that provide habitat for thousands of marine creatures. These forests also contribute millions of dollars through fisheries and tourism, sequester carbon dioxide, protect coastlines and are culturally significant for coastal First Nations,” said Dr. Prentice.

Researchers and project partners hope the discovery will help guide management and recovery efforts for sea stars and impacted ecosystems.

“This finding opens up exciting avenues to expand the network of researchers able to develop solutions for recovery of the species,” said Jono Wilson, the director of ocean science for The Nature Conservancy’s California chapter, which helped support the research. “We are actively pursuing studies looking at genetic associations with disease resistance, captive breeding and experimental introduction of captively-raised stars back into the wild to understand the most effective strategies and locations to reintroduce sunflower sea stars into the wild.”

Journal Reference:

Prentice, M.B., Crandall, G.A., Chan, A.M. et al., ‘Vibrio pectenicida strain FHCF-3 is a causative agent of sea star wasting disease’, Nature Ecology & Evolution (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41559-025-02797-2

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Alex Walls | University of British Columbia (UBC)

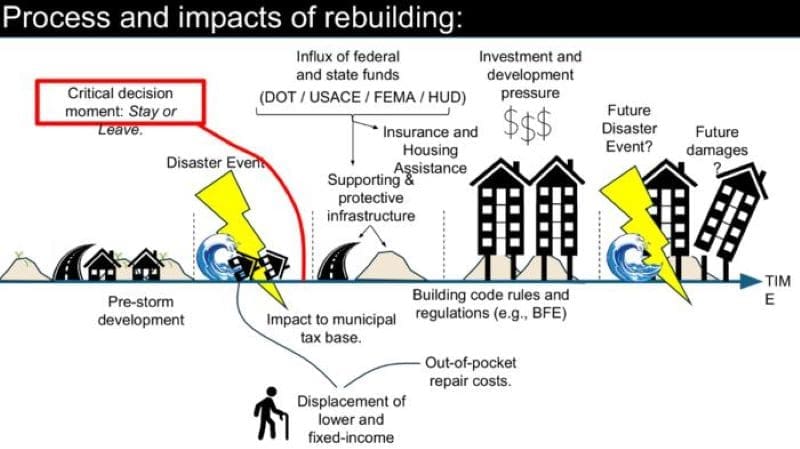

After the storm: to rebuild or relocate?

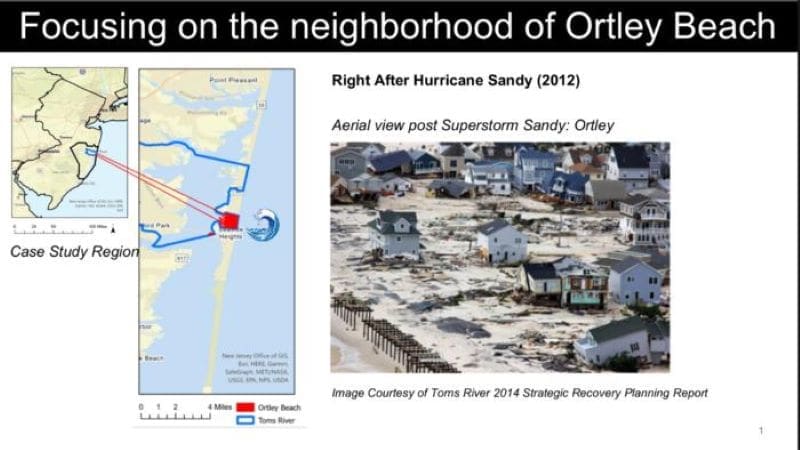

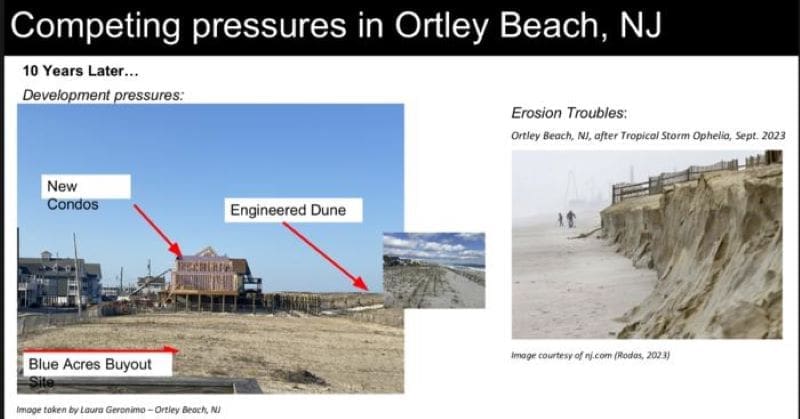

As climate hazards escalate, communities facing repetitive disasters in high-risk areas must weigh the economic and social trade-offs of rebuilding versus relocating. A Risk Analysis study has found that residents and government officials may have different ideas about how public funds should be spent to adapt to extreme weather events brought on by climate change.

What they did:

To examine the process of rebuilding in a coastal community, Rutgers University researchers focused on Ortley Beach, a barrier island neighborhood in Toms River, New Jersey. Ortley Beach was devastated by Superstorm Sandy in 2012, with around 200 homes destroyed. Ten years after the storm (in the summer of 2022), the scientists conducted detailed key-informant interviews with Ortley Beach residents and local, state, and federal officials with the help of the Ortley Beach Voters and Taxpayers Association (OBVTA).

The central question asked was whether public resources should support staying or leaving the island in the wake of severe repetitive flood losses. A questionnaire investigated their values, beliefs and worldviews – to explore how those relate to their preferences for federal spending. Analysis of the results revealed important findings that could apply to “many communities on the frontlines of rising sea level and storm surge – like those in Florida, Texas, and Louisiana,” says lead author Laura Geronimo, a 2024 doctoral graduate of Rutgers Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy Ph.D. and current Knauss Fellow with NOAA.

What they found:

- Despite conflicting values, beliefs, and worldviews, all stakeholders identified the economic impacts of adaptation – like home elevations, beach nourishment, or buyouts – as a top concern, citing strain on household budgets, municipal finances, and challenges in prioritizing limited state and federal funding.

- Residents emphasized the steep costs of post-Sandy rebuilding and home elevation, with some incurring over $100,000 in out-of-pocket expenses. Many also mentioned sharp increases in insurance premiums after Sandy.

- Long-term residents were torn about whether federal and state subsidies should support efforts to stay or leave, citing concerns about how subsidies may create perverse incentives, distort coastal housing markets and catalyze gentrification. Many of these residents expressed support for considering alternatives like voluntary buyouts and nature-based solutions in long-range planning: “If we don’t do something to plan it out, it is just going to be a bunch of homes underwater”.

- State and federal officials also supported considering buyouts in long-range planning, echoing these concerns.

- In contrast, local officials favored rebuilding high-value properties and protecting exposed barrier island communities despite obvious risk, referencing the need to preserve tax revenues from high-value properties.

Local officials tended to hold more individualistic-hierarchical worldviews, weaker beliefs in climate science and favored actions to protect high-value properties to preserve the tax base while externalizing costs. In contrast, some residents and most state and federal officials held more community-egalitarian worldviews, stronger beliefs in climate science and preferences for long-term adaptation strategies to reduce risk, including property buyouts.

The study notes that, in 2022, the local government was Republican and the state and federal government was Democratic, while residents had mixed political ideologies.

“The contrast between local officials and residents reflects a broader cultural tension of whether to prioritize property values or human well-being when justifying protection measures,” says Geronimo.

Why it’s important:

In the U.S., high-risk areas – particularly coastal regions – face dual pressures: escalating flood risk and intensifying development. Federal fiscal arrangements, including disaster aid, insurance and hazard mitigation programs, have historically enabled rebuilding in the same exposed locations. But this approach is under growing scrutiny. Critics argue that – in some areas experiencing severe repetitive losses – public funds may be more effectively used to support community-led relocation through tools like property buyouts and assistance.

While the Biden administration invested heavily in hazard mitigation, the Trump administration has rescinded billions in funds, according to Geronimo. “Communities like those on the Jersey Shore, which rely heavily on federal transfers, may soon face a fiscal cliff,” she says. “Our study reveals that residents and officials across all levels of government are concerned about the financial implications of coastal risk strategies – underscoring the need to clearly demonstrate the long-term economic benefits of alternatives like voluntary relocation and to bolster both household and local fiscal resilience to climate and political shocks.”

Geronimo and her co-authors recommend enhancing individual and local financial resilience through diversified revenue streams, proactive risk-based planning, innovative insurance models, and more transparent accounting of the long-term costs of rebuilding in high-risk areas.

The methods and findings from this research are also valuable for communities experiencing extreme or repetitive losses from other types of hazards, including fire, tornadoes and extreme precipitation – such as the recent tragedy along the Guadalupe River in Texas Hill Country. “The parallel examples of Ortley Beach and Camp Mystic illustrate that when rebuilding is allowed in repetitive loss areas, lives are at stake,” says Geronimo.

Journal Reference:

Geronimo, L., Payne, W.B., Andrews, C.J., Gilmore, E.A. and Kopp, R.E., ‘Cultural and Institutional Factors Driving Severe Repetitive Flood Losses: Insights From the Jersey Shore’, Risk Analysis (2025). DOI: 10.1111/risa.70091

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Society for Risk Analysis (SRA)

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay