Summary:

Seals feeding near glacier fronts in Greenland have fuller stomachs than those caught farther away, according to a new study in Communications Earth & Environment. The research provides direct evidence that tidewater glacier fronts act as key feeding grounds for Arctic marine predators, a view that has been widely discussed but rarely tested with field data.

Led by Project Assistant Professor Monica Ogawa of the National Institute of Polar Research in Japan, the team worked with Inuit hunters in Inglefield Bredning – also known as Kangerlussuaq – in northwest Greenland. By comparing the exact capture locations of hunted ringed seals with analyses of their stomach contents, the researchers were able to link recent feeding activity to specific areas. Because seals digest prey quickly, stomach contents reflect meals eaten only hours earlier, allowing the team to examine fine-scale spatial patterns.

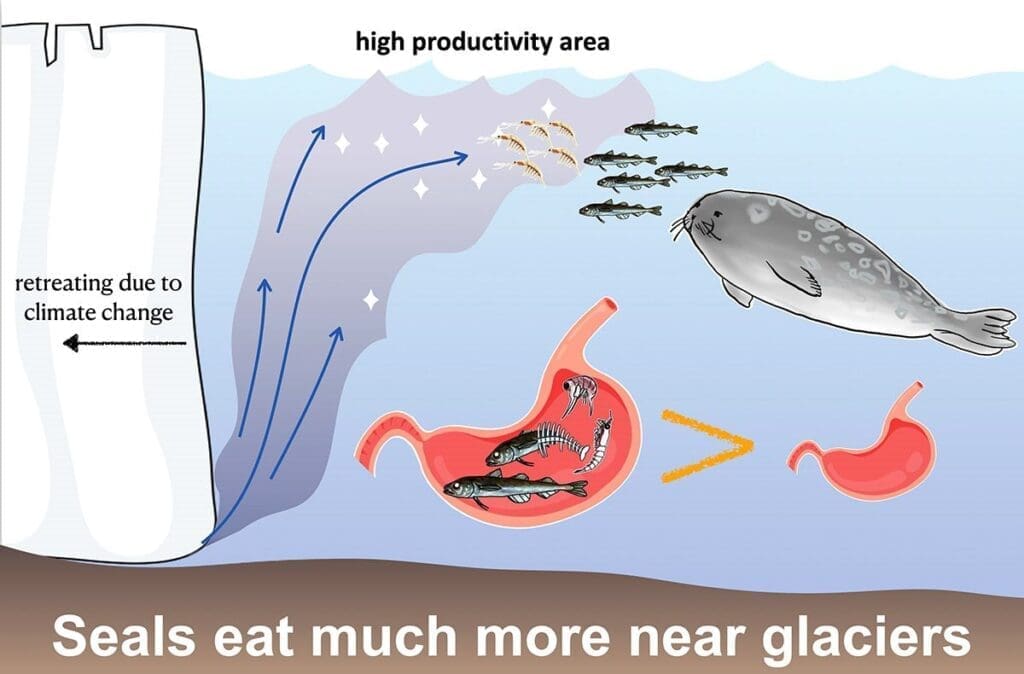

The results showed that seals taken close to glacier fronts had consumed more prey, particularly polar cod, than those harvested farther away. Diet also varied by location, suggesting that seals adjust their foraging strategies to local prey availability. As Arctic glaciers retreat and many tidewater glaciers pull back onto land, the loss of these productive fronts could alter seal diet, distribution and body condition, with wider consequences for Arctic ecosystems and communities that depend on them.

— Press Release —

Glacial feast: Seals caught closer to glaciers had fuller stomachs

Studying foraging behavior in marine mammals is especially difficult. Unlike terrestrial animals, which can often be directly observed, marine mammals feed underwater and across vast, remote areas, making it challenging to determine where and what they eat. Most diet studies rely on stomach contents of stranded animals, making it impossible to know where or when feeding occurred.

In the Arctic, however, where Inuit communities hunt marine mammals as part of a subsistence lifestyle, this limitation can be overcome. By comparing hunted locations with the stomach contents of harvested animals, researchers can determine where and what marine mammals had been feeding.

In a recent study led by Project Assistant Professor Monica Ogawa from the National Institute of Polar Research, Japan, researchers collaborated with Inuit hunters around Inglefield Bredning (Kangerlussuaq), Greenland, to investigate spatial differences in the diet of ringed seals in relation to capture locations. The findings were published in Communications Earth & Environment journal on February 18, 2026.

“Stomach content analysis is one of the most classical methods for studying animal diets. However, because stomach contents reflect only very recent feeding – within just a few hours for seals – this approach has often been seen as a limitation. We turned this limitation into an advantage by comparing what seals had eaten with where they were captured, allowing us to investigate recent feeding activity in specific locations. This approach offers a new way to understand the feeding behavior of marine mammals,” says Dr. Ogawa.

The findings revealed not only the importance of glacier fronts as feeding grounds for seals, but also that diet varies with distance from the glacier, indicating that the loss of these habitats could have wider consequences for Arctic marine ecosystems. As Arctic glaciers continue to retreat, many tidewater glaciers are shrinking back onto land, eliminating the upwelling processes that create these feeding hotspots.

The researchers warn that the disappearance of glacier-front foraging grounds could force seals to change their diet, distribution, and body condition, which in turn would affect their predators, both animals, such as polar bears, and Inuit communities that rely on seals.

“This study was made possible through the cooperation of many Inuit hunters. By working together with Inuit communities, we could obtain data – both in quality and quantity – that scientists alone could never achieve. And above all, this collaboration made the research truly enjoyable,” says Dr. Ogawa.

***

About Project Assistant Professor Monica Ogawa from National Institute of Polar Research, Japan

Dr. Monica Ogawa is a project Assistant Professor at the National Institute of Polar Research, Japan. Her research focuses on the ecology of marine mammals, with a particular emphasis on collaborative research with Inuit communities in the Arctic. She has been felicitated with the Young Researcher Excellence Award, ArCS II, and multiple Best Presentation awards. Her work has been featured in prominent media programs, including NHK Frontiers (Scientists and Indigenous People: The Truth About the Arctic) and NHK Science ZERO (Exploring the Frontline of Climate Change in the Arctic with Indigenous Peoples).

Journal Reference:

Ogawa, M., Jansen, T., Rosing-Asvid, A. et al., ‘Tidewater glacier fronts are an important foraging ground for an Arctic marine predator’, Communications Earth & Environment 7, 167 (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-025-03174-4

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Research Organization of Information and Systems (ROIS)

Featured image: Tidewater glacier in Inglefield Bredning. Credit: Monica Ogawa | NIPR