Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press daily roundup (June 27, 2025), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

Some of your AI prompts could cause 50 times more CO2 emissions than others

Researchers have now compared 14 models and found that complex answers cause more emissions than simple answers, and that models that provide more accurate answers produce more emissions. Users can, however, to an extent, control the amount of CO2 emissions caused by AI by adjusting their personal use of the technology, the researchers said.

No matter which questions we ask an AI, the model will come up with an answer. To produce this information – regardless of whether than answer is correct or not – the model uses tokens. Tokens are words or parts of words that are converted into a string of numbers that can be processed by the LLM.

This conversion, as well as other computing processes, produce CO2 emissions. Many users, however, are unaware of the substantial carbon footprint associated with these technologies. Now, researchers in Germany measured and compared CO2 emissions of different, already trained, LLMs using a set of standardized questions.

“The environmental impact of questioning trained LLMs is strongly determined by their reasoning approach, with explicit reasoning processes significantly driving up energy consumption and carbon emissions,” said first author Maximilian Dauner, a researcher at Hochschule München University of Applied Sciences and first author of the Frontiers in Communication study. “We found that reasoning-enabled models produced up to 50 times more CO2 emissions than concise response models.”

‘Thinking’ AI causes most emissions

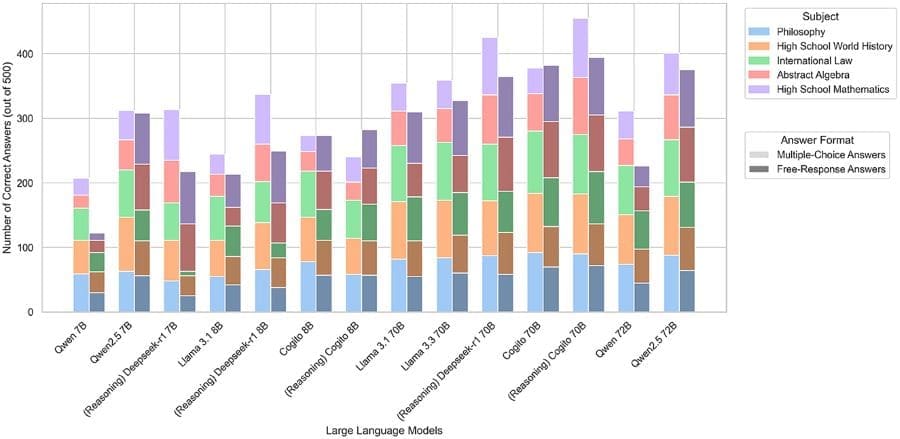

The researchers evaluated 14 LLMs ranging from seven to 72 billion parameters on 1,000 benchmark questions across diverse subjects. Parameters determine how LLMs learn and process information.

Reasoning models, on average, created 543.5 ‘thinking’ tokens per questions, whereas concise models required just 37.7 tokens per question. Thinking tokens are additional tokens that reasoning LLMs generate before producing an answer. A higher token footprint always means higher CO2 emissions. It doesn’t, however, necessarily mean the resulting answers are more correct, as elaborate detail that is not always essential for correctness.

The most accurate model was the reasoning-enabled Cogito model with 70 billion parameters, reaching 84.9% accuracy. The model produced three times more CO2 emissions than similar sized models that generated concise answers. “Currently, we see a clear accuracy-sustainability trade-off inherent in LLM technologies,” said Dauner. “None of the models that kept emissions below 500 grams of CO2 equivalent achieved higher than 80% accuracy on answering the 1,000 questions correctly.” CO2 equivalent is the unit used to measure the climate impact of various greenhouse gases.

Subject matter also resulted in significantly different levels of CO2 emissions. Questions that required lengthy reasoning processes, for example abstract algebra or philosophy, led to up to six times higher emissions than more straightforward subjects, like high school history.

Journal Reference:

Dauner M and Socher G, ‘Energy costs of communicating with AI’, Frontiers in Communication 10, 1572947 (2025). DOI: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1572947

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Frontiers

Research news from the Ecological Society of America’s journals

The Ecological Society of America (ESA) presents a roundup of five research articles recently published across its esteemed journals. Widely recognized for fostering innovation and advancing ecological knowledge, ESA’s journals consistently feature illuminating and impactful studies.

This compilation of papers explores the challenges environmental changes pose to meerkats, a pathway to protected area management alongside Tribal Nations, the effects of marine heatwaves on marine fish, increased methane emissions in drylands, and the inadequacy of current frameworks for predicting animals’ adaptability to climate change.

From Ecological Monographs:

How meerkats take the heat (and drought) | Author contact: Jack Thorley

Environmental changes in their Kalahari Desert homeland are putting meerkats to the ultimate test. In a setting where hot and dry conditions vary from season to season and year to year, literally making the difference between life and death, researchers have tracked a population of meerkats for nearly three decades to understand how these desert specialists handle environmental change.

They found that wetter summer conditions led to a profusion of plants and insects; with so many more bugs, roots and tubers to gorge on, meerkat body size and overall condition improved. On the other hand, heat is a real challenge for these small mammals, and they struggled to find enough food when temperatures climbed above 37°C (98.6°F). Luckily for the meerkats, over the course of the study the hottest days tended to occur when the summer rains left the desert at its greenest peak, giving the meerkats an opportunity to recover as soon as temperatures dipped.

Though safe for the moment, meerkats face significant challenges if expected shifts in climate patterns play out. A better understanding of the impacts that changes in rainfall and temperature will have is needed to ensure a future for this little African mongoose and other desert species.

Read the article: Linking climate variability to demography in cooperatively breeding meerkats

From Earth Stewardship:

A pathway to true co-management with Tribal Nations | Author contact: Lara A. Jacobs

Despite recent progress toward greater inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge, management of U.S. parks and protected areas remains firmly entrenched within Western views of conservation and land use. Building on a model based on studies of power dynamics, the authors of this study first identify the barriers that continue to impede incorporation of traditional knowledge in park management. From there, they construct a framework for shifting oversight of protected areas from conventional approaches to strategies that emerge from more equitable collaboration between Western and Native perspectives, with a gradual shift toward Indigenous-led administration.

Rooting management of the nation’s public natural areas in Indigenous values, knowledge systems and leadership would both enhance conservation efforts and deepen recognition of Tribal Nations sovereignty and self-determination.

Read the article: U.S. parks and protected area power structures: From historic policies to Indigenous futurities

From Ecological Applications:

Failure to launch: Rockfish delay adulthood during marine heatwaves | Author contact: R. Claire Rosemond

Marine fish will grow at a faster rate and mature earlier as ocean temperatures warm — or so goes the prevailing theory. But the results of a recent survey of black rockfish in the coastal waters of the U.S. Pacific Northwest may upend this tidy premise. Measurements of young female rockfish caught during strong marine heatwaves — periods when expanses of ocean water are considerably hotter than normal — revealed that juveniles did indeed grow faster, as was predicted. Contrary to expectations, however, females took longer to mature during heatwaves than under cooler conditions.

This delayed onset of adulthood suggests that current frameworks fail to capture the full complexity of the relationship between water temperature and fish development, muddling efforts to predict how fish will respond to the warmer oceans and more frequent marine heatwaves looming on the horizon.

Read the article: Elevated fish growth yet postponed maturation during intense marine heatwaves

From Ecosphere:

Wetting of drylands increases methane emissions | Author contact: Uthara Vengrai

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, and scientists have long assumed that dryland ecosystems like deserts and arid grasslands and shrublands soak up more methane than they emit. But new research shows that the introduction of irrigation and artificial wetlands for agriculture is altering this equation. Though covering a mere 1% of the landscape, constructed wetlands in Wyoming were found to release more methane into the atmosphere than is removed by surrounding ecosystems (primarily sagebrush), due to changes in soil characteristics, soil microbial communities and a host of other factors.

This large effect of irrigation on methane absorption and release can effectively transform dryland ecosystems into net producers of methane, with considerable implications for future warming and subsequent climate change.

Read the article: Land use change converts temperate dryland landscape into a net methane source

From Ecology:

Animal heat–cold tolerance depends on scale | Author contact: Miguel Tejedo

New evidence suggests that how animals cope with extreme heat and cold depends on the scale of study. Using data extracted from other studies on hundreds of species, the researchers found that across large geographic expanses, the heat tolerance of many amphibians, insects and reptiles remained constant, while their cold tolerance varied much more from place to place — a pattern consistent with the results of previous research. Yet at smaller scales that better reflect where these animals live (an outcrop of rocks, say, or a stand of trees), the opposite was observed, with heat tolerance fluctuating more than the animals’ abilities to cope with cold.

This reversal at local levels is cause for hope, as even a little bit of additional thermal headroom could increase a species’ chance for survival in a rapidly warming world. Moreover, the findings serve as a warning that overreliance on global and regional patterns while ignoring the role of local-scale patterns may lead us to underestimate an animal’s true resilience to changing environmental conditions.

Read the article: High thermal variation in maximum temperatures invert Brett’s heat-invariant rule at fine spatial scales

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Ecological Society of America (ESA)

New homes for endangered native skink aim to improve survival chances

Climate change and habitat loss are affecting animal populations around the world and reptiles such as South Australia’s own endangered pygmy bluetongue are susceptible to higher temperatures and declining long-term rainfall trends.

Flinders University scientists are working on securing a sustainable future for the burrow-dwelling endemic skink (Tiliqua adelaidensis) by assessing their suitability to cooler and slightly greener locations, below their usual range in the state’s drier, hotter northern regions.

While the lizards take time to acclimatise to their new homes, translocation remains one of the more important ways to conserve rare species and mitigate extinction risk to climate and habitat changes.

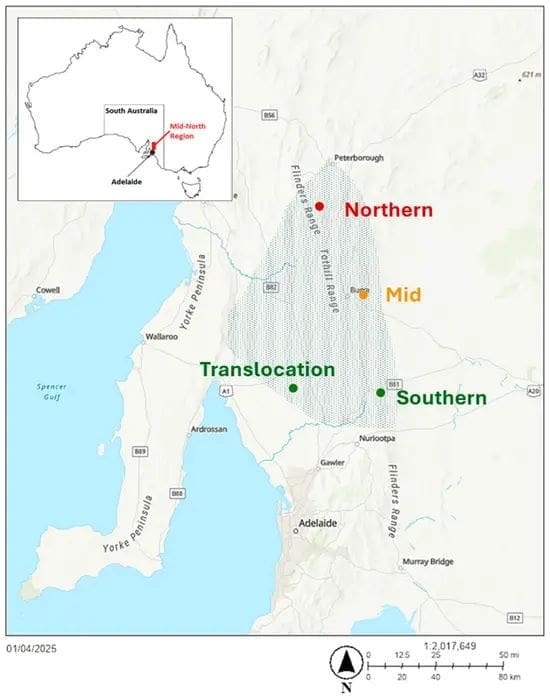

The latest research, outlined in a new article published in Biology, compared the ability of three separate pygmy bluetongue lizard populations to withstand different microclimates in South Australia – between the northern Flinders Ranges near Jamestown, Mid North near Burra, and southern-most translocation sites near Tarlee and Kapunda.

The study, led by PhD candidate Deanne Trewartha from the College of Science and Engineering, says moving wildlife adapted to a hotter, drier location to another microclimate can mean exposure to different temperatures, water availability and humidity and needs extensive assessment.

“We need to understand how this species, which are highly dependent on body temperature, adapt to cooler and often wetter seasons in these new environments,” says Ms Trewartha, from the Flinders University Lab of Evolutionary Genetics and Sociality (LEGS) research group.

Reptiles rely on attaining certain body temperatures for basic bodily function and increasing body temperature raises dehydration risk.

She says the research so far suggests acclimatisation to new sites may take longer than two years for all three populations and may vary with latitude of origin.

“Despite this acclimatisation delay, our results indicate that these lizards may cope with translocation as a mitigation strategy in the longer term. Further monitoring of the three lineages will continue to see any behavioural variations in wet versus dry seasons and the long-term behavioural acclimatisation periods for translocations.”

Australia has the highest reptile diversity in the world, and Flinders University Professor of Biodiversity and Ecology Mike Gardner says translocation may be the only way for the conservation of numerous small burrow-dwelling reptiles, other ectotherms and reptile species in future.

“With high biodiversity loss, translocation to ‘future-suitable’ sites is becoming increasingly urgent for the conservation of numerous reptile species,” says Professor Gardner, who leads an Australian Research Council Linkage project to study various pygmy bluetongue groups at different latitudes in South Australia.

“So far, these three populations are showing various responses to their new locations, but behavioural variations may not be detrimental in the long term and may potentially aid animals in acclimatising to changed environments to optimise their chance their survival.”

A previous study published last year (in Animal Conservation) noted differences between the way the colonies behaved.

From spring 2020 to autumn 2021, monthly monitoring of behaviours found the translocated southern lineage lizards showed significantly less daily activity and were active at lower temperatures and higher humidity than northern lineage lizards.

Southern lineage lizards allowed a human observer to approach closer as base-of-burrow humidity increased, while northern lineage lizards were quicker to retreat into burrows, at both source and translocation sites.

Journal Reference:

Trewartha, D. M., Godfrey, S. S., & Gardner, M. G., ‘Lizards, Lineage and Latitude: Behavioural Responses to Microclimate Vary Latitudinally and Show Limited Acclimatisation to a Common Environment After Two Years’, Biology 14 (6), 622 (2025). DOI: 10.3390/biology14060622

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Flinders University

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay