Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press roundup (December 8, 2025), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

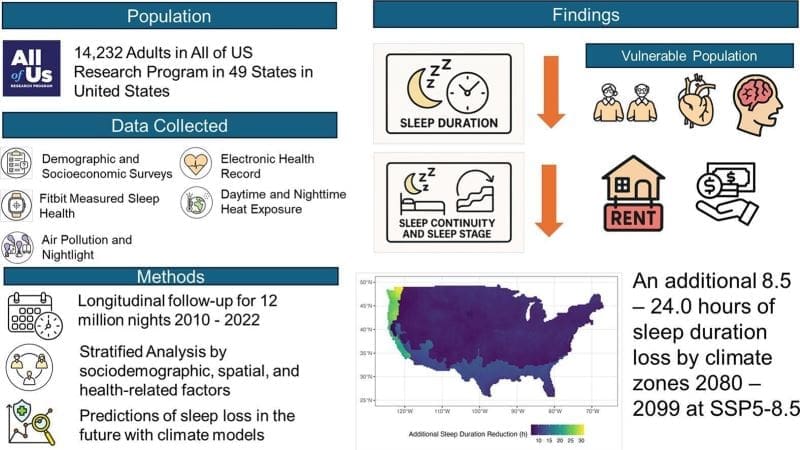

Study links rising temperatures to reduced sleep in US adults

Higher nighttime temperatures are linked to shorter sleep times and lower sleep quality, especially for people with chronic health conditions, lower socioeconomic status, or those living on the West Coast, according to a new USC study. Researchers estimate that by 2099, people could lose up to 24 hours of sleep each year due to heat, highlighting the potential impact of climate change on sleep health.

The findings were just published in the journal Environment International.

Warm weather can disturb sleep in several ways, including by preventing the body from cooling down, triggering a stress response, and reducing time spent in deep sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. Poor sleep can in turn increase risk for a number of health problems, including heart and respiratory issues and mental health concerns.

“We already know that when there are extreme heat events, more people die from cardiovascular disease and pulmonary disease. What will this mean for population health as global temperatures continue to rise?,” said Jiawen Liao, PhD, a postdoctoral research associate in population and public health sciences at the Keck School of Medicine of USC and first author of the study.

Past research has documented the link between rising temperatures and sleep problems, but most studies lacked details on the demographics, socioeconomic, and health information of participants. That prevented researchers from gaining a full understanding of who is most at risk and how best to respond.

The new study, done in collaboration with Harvard Medical School/Brigham and Women’s Hospital and funded in part by the National Institutes of Health, leverages data from 14,232 U.S. adults in the All of Us Research Program to begin filling in those gaps. All of Us is a longitudinal study that includes detailed data from surveys, health records, wearable devices and other sources.

“This work is an important step toward understanding how sleep is affected by environmental stressors like heat, which can increase the risk of disease and even death,” Liao said. “If we can help people sleep better, we may be able to reduce illness and save lives.”

Warmer nights, shorter sleep

The researchers obtained data on U.S. adults enrolled in All of Us that was collected between 2010 and 2022. Along with detailed demographic, socioeconomic and health information, participants also shared their FitBit data, giving the research team a rich picture of sleep patterns.

In total, the researchers analyzed more than 12 million nights of sleep, looking at how long people slept and how easily they fell asleep. They also examined 8 million nights of data on sleep stages and how often sleep was interrupted. Finally, they used location and meteorological data to find out whether sleep patterns were linked to changing temperatures.

They found that a 10-degree Celsius increase in daytime temperature was associated with 2.19 minutes of lost sleep, while a 10-degree nighttime temperature increase was associated with a loss of 2.63 minutes. The effects were greater among females, people of Hispanic ethnicity, people with chronic diseases, and those with a lower socioeconomic status.

“This may seem like a small amount, but when it adds up across millions of people, the total impact is enormous,” Liao said.

The researchers also found that effects differed by season, with more sleep loss occurring from June to September, and geographic region, with people in West Coast areas losing nearly three times as much sleep as people in other regions. Based on the findings, the researchers project that U.S. adults could lose between 8.5 and 24 hours of sleep per year by 2099, depending on their location.

In addition to shorter sleep times, rising temperatures were also associated with more disrupted sleep throughout the night and more time spent awake in bed.

Improving sleep and health

A key takeaway from the study is that some populations face higher risks than others. Targeting interventions and policy changes to those groups may be particularly impactful, Liao said.

For example, policymakers in West Coast regions could promote access to air conditioning, expand green roofs or increase urban green space. Building codes that require better insulation, improved ventilation or heat-resistant design could also be strengthened in these areas to protect population health.

Next, Liao and his colleagues plan to explore whether interventions designed to improve sleep, such as indoor cooling, green roof or sleep hygiene programs, can help reduce the harmful effects of heat exposure. They aim to test whether improving sleep through these interventions can reduce heat-related health problems and lower the risk of disease and death.

Journal Reference:

Jiawen Liao, Rima Habre, Erika Garcia, Sandrah P. Eckel, Joe Kossowsky, Megan M. Herting, Wu Chen, Chenyu Qiu, Zhenchun Yang, Rob McConnell, Frank Gilliland, Susan Redline, Zhanghua Chen, ‘Impact of heat exposure on sleep health and its population vulnerability in the United States’, Environment International 206, 109942 (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.envint.2025.109942

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Zara Abrams | Keck School of Medicine of USC

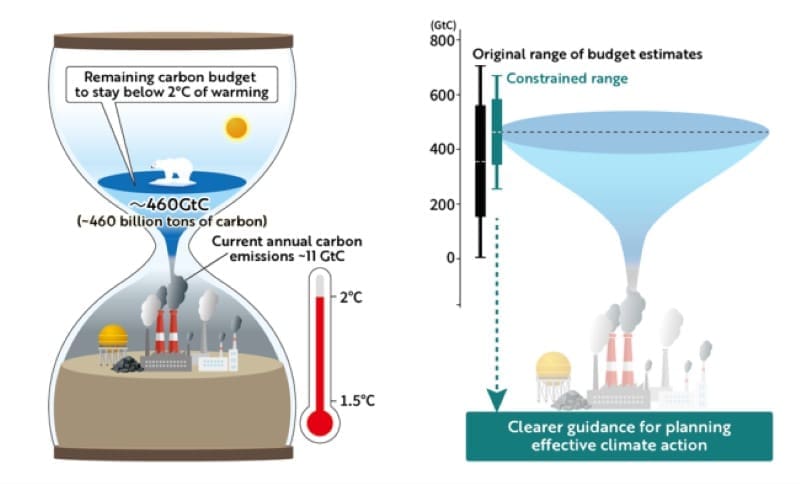

New approach narrows uncertainty in future warming and remaining carbon budget for 2 °C

How much the planet warms with each ton of carbon dioxide remains one of the most important questions in climate science, but there is uncertainty in predicting it. This uncertainty hinders governments, businesses and communities from setting clear emission-reduction targets and preparing for the impacts of climate change. The changes in atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations and surface temperatures are shaped by complex feedback between land, ocean, atmosphere and ecosystems, and this feedback can either amplify or mitigate warming. Reducing this uncertainty is critical to keeping the international goal of limiting warming to 2 °C within reach.

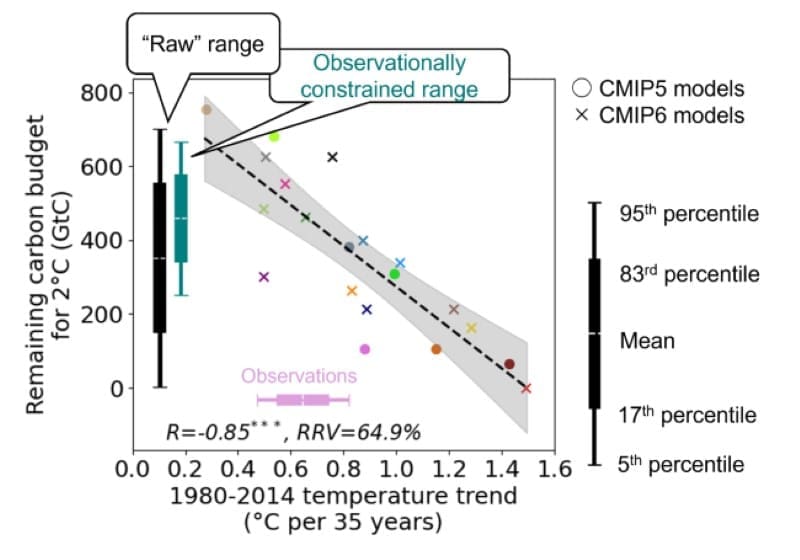

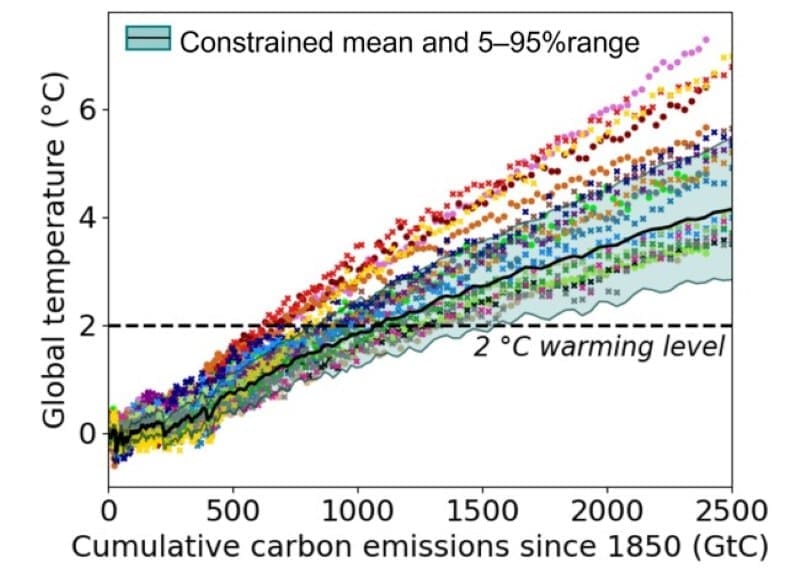

The team of researchers in Japan has developed an innovative approach to improve projection accuracy by combining climate model projections with observational data. The analysis was conducted using the results of numerical experiments on 20 state-of-the-art Earth System Models that participated in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5 and CMIP6), which contributed to the Fifth and Sixth Assessment Reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The team examined not only how climate models respond to rising carbon dioxide concentrations but also how human carbon dioxide emissions affect atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations – a process governed by the Earth’s carbon cycle. This involves how much of the emitted carbon dioxide remains in the atmosphere versus how much is absorbed by forests, soils and oceans.

The analysis revealed that many models overestimate global warming relative to past carbon dioxide emissions. By bringing observations into the picture, the researchers narrowed the uncertainty in projected 21st-century warming and refined estimates of the remaining carbon budget – the total carbon dioxide that can still be emitted while keeping warming level below 2 °C.

Previous studies that did not account for the degree of agreement with observations estimated the remaining carbon budget for limiting warming to 2 °C at about 352 billion tons of carbon, with a wide uncertainty range of 2–702 billion tons. By taking into account the degree of agreement between the Earth system model and observations, the analysis refined this estimate to a mean of 459 billion tons with a narrower uncertainty range of 251–666 billion tons, thereby substantially improving projection accuracy (Figure 1).

Figure 2 illustrates how taking into account the degree of agreement between model results and past observations leads to more accurate projections. In climate research, models that better reproduce the observed global temperature rise (horizontal pink bar) are considered more reliable for future predictions. By giving greater weight to such models, the analysis reduces the spread of estimates for the remaining carbon budget (vertical green bar) compared with the full model range (vertical black bar), thereby improving prediction confidence.

This study sheds light on why estimates of future warming shift when emissions are used instead of concentrations. In the real world, not all of the carbon dioxide we emit stays in the air – much of it is absorbed by forests, soil and oceans. How models represent this “airborne fraction” and the split between land and ocean sinks strongly influences their projections. In many simulations, models warmed the planet too quickly and underestimated how much carbon the land and oceans could take up.

By comparing these processes with observations, the researchers showed that some of the most extreme warming projections are less likely, which tightens the range of outcomes (Figure 3). Previous studies have not been able to improve the accuracy of Earth system models’ predictions of both land and ocean carbon dioxide uptake and temperature change. This study is the first to achieve such improvement using the approach illustrated in Figure 2.

These results strengthen the scientific foundation for climate policy by narrowing the range of future warming and the remaining carbon budget. More reliable projections give governments clearer guidance for setting emission-reduction targets, reinforce the credibility of net-zero pledges, and help communities prepare for climate impacts. Beyond the immediate policy relevance, the new framework also offers a valuable tool for future climate assessments, including the upcoming IPCC AR7, where it can be extended to other components of the Earth system.

Yet the broader message is one of urgency: even with refined estimates and a somewhat larger remaining carbon budget, current emissions of about 11 billion tons of carbon per year would still deplete the budget for limiting warming to 2 °C within just a few decades. Our results demonstrate the imperative to take urgent action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Journal Reference:

Irina Melnikova, Tokuta Yokohata, Hideo Shiogama, ‘Narrowed uncertainty in future global temperature and remaining carbon budget’, One Earth online, 101526 (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.oneear.2025.101526

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by National Institute for Environmental Studies (NIES)

Greenhouse gases to intensify extreme flooding in the Central Himalayas

Geographers at Durham University, UK, simulated the risk of increased flooding on the Karnali River, which spans Nepal and China and has the potential to impact communities in Nepal and India.

They found that extreme floods – those with a 1% chance of happening within a year – could increase in size by 22% and 26% between 2020 and 2059, compared to flooding seen in the region between 1975 and 2014.

This increase is expected to be within 37% and 43% between 2060 and 2099 with medium greenhouse gas emissions. High greenhouse gas emissions could see the size of extreme floods increase by between 73% and 84% in the same period.

The findings, published in the journal Scientific Reports, highlight the scale of the increase in flooding that communities in the Central Himalayas could experience.

The researchers say their study could inform local flood hazard management in the region.

The floodplains of the Central Himalayan foreland are among the most flood-affected areas of the world.

In September 2024, floods caused 236 deaths and displaced 8,400 people, along with damage worth 1% of Nepal’s gross domestic product (GDP). By 2050, flood damages are projected to account for 2.2% of Nepal’s annual GDP.

Flooding in the Himalayan foreland in Nepal also has consequences for food insecurity and the outbreak of epidemics, which would likely be exacerbated by higher greenhouse gas emissions.

Dr Ivo Pink, in the Department of Geography/Institute of Hazard, Risk and Resilience, Durham University, said: “The densely populated Central Himalayan foreland is prone to flooding, and our findings show that the intensity of extreme floods is only going to get worse across the coming century as greenhouse gas emissions increase.

“Floods with a 1% chance of happening within a year could occur once every five to 10 years at the end of the century.

“This shows the urgent need to cut global greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible, because flood hazards will continue to increase for decades after the emission peak.”

The Durham researchers coupled climate projections from different research centres worldwide with hydrological simulations and statistical analysis.

Increased rainfall would be the largest source of floodwater, rather than snow or glacier melt.

The study shows that large sets of climate models are needed to predict changes in extreme floods because they occur infrequently, the researchers add.

Professor Sim Reaney, in the Department of Geography, Durham University, said: “It is often stated that ‘all forecasts are uncertain, especially those about the future’. Our study addresses this problem of the uncertainties in potential future flood hazards in Nepal by combining uncertainties from both climate and river flow simulations.

“We can then see the range of possibilities for the future and make effective decisions to reduce flood hazards and improve the livelihoods of people living on the Central Himalayan foreland.”

The research was funded by a Charles Wilson Doctoral Studentship through the Institute of Hazard, Risk and Resilience. The simulations were carried out on high-performance computers provided by the Advanced Research Computing Unit at Durham University.

Journal Reference:

Pink, I., Reaney, S.M., Hardy, R.J. et al., ‘Increased rainfall-runoff drives flood hazard intensification in Central Himalayan river systems’, Scientific Reports 15, 42277 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-26815-2

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Durham University

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay