Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press roundup (December 15, 2025), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

MIT researchers find a new approach to carbon capture could slash costs

Capturing carbon dioxide from industrial plants is an important strategy in the efforts to reduce the impact of global climate change. It’s used in many industries, including the production of petrochemicals, cement, and fertilizers.

MIT chemical engineers have now discovered a simple way to make carbon capture more efficient and affordable, by adding a common chemical compound to capture solutions. The innovation could cut costs significantly and enable the technology to run on waste heat or even sunlight, instead of energy-intensive heating.

Their new approach uses a chemical called tris – short for tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane – to stabilize the pH of the solution used to capture CO₂, allowing the system to absorb more of the gas at relatively low temperature. The system can release CO₂ at just 60 degrees Celsius (140 degrees Fahrenheit) – a dramatic improvement over conventional methods, which require temperatures exceeding 120 °C to release captured carbon.

“It’s something that could be implemented almost immediately in fairly standard types of equipment,” says T. Alan Hatton, the Ralph Landau Professor of Chemical Engineering Practice at MIT and the senior author of the study.

Youhong (Nancy) Guo, a recent MIT postdoc who is now an assistant professor of applied physical sciences at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, is the lead author of the paper, which appears in Nature Chemical Engineering.

More efficient capture

Using current technologies, around 0.1 percent of global carbon emissions is captured and either stored underground or converted into other products.

The most widely used carbon-capture method involves running waste gases through a solution that contains chemical compounds called amines. These solutions have a high pH, which allows them to absorb CO₂, an acidic gas. In addition to traditional amines, basic compounds called carbonates, which are inexpensive and readily available, can also capture acidic CO₂ gas. However, as CO₂ is absorbed, the pH of the solution drops quickly, limiting the CO₂ uptake capacity.

The most energy-intensive step comes once the CO₂ is absorbed, because both amine and carbonate solutions must be heated to above 120 °C to release the captured carbon. This regeneration step consumes enormous amounts of energy.

To make carbon capture by carbonates more efficient, the MIT team added tris into a potassium carbonate solution. This chemical, commonly used in lab experiments and found in some cosmetics and the Covid-19 mRNA vaccines, acts as a pH buffer – a solution that helps prevent the pH from changing.

When added to a carbonate solution, positively charged tris balances the negative charge of the bicarbonate ions formed when CO₂ is absorbed. This stabilizes the pH, allowing the solution to absorb triple the amount of CO₂.

As another advantage, tris is highly sensitive to temperature changes. When the solution full of CO₂ is heated just slightly, to about 60 °C, tris quickly releases protons, causing the pH to drop and the captured CO2 to bubble out.

“At room temperature, the solution can absorb more CO₂, and with mild heating it can release the CO₂. There is an instant pH change when we heat up the solution a little bit,” Guo says.

A simple swap

To demonstrate their approach, the researchers built a continuous-flow reactor for carbon capture. First, gases containing CO₂ are bubbled through a reservoir containing carbonate and tris, which absorbs the CO₂. That solution then is pumped into a CO₂ regeneration module, which is heated to about 60 °C to release a pure stream of CO₂.

Once the CO₂ is released, the carbonate solution is cooled and returned to the reservoir for another round of CO₂ absorption and regeneration.

Because the system can operate at relatively low temperatures, there is more flexibility in where the energy could come from, such as solar panels, electricity, or waste heat already generated by industrial plants.

Swapping in carbonate-tris solutions to replace conventional amines should be straightforward for industrial facilities, the researchers say. “One of the nice things about this is its simplicity, in terms of overall design. It’s a drop-in approach that allows you to readily change over from one kind of solution to another,” Hatton says.

When carbon is captured from industrial plants, some of it can be diverted into the manufacture of other useful products, but most of it will likely end up being stored in underground geological formations, Hatton says.

“You can only use a small fraction of the captured CO₂ for producing chemicals before you saturate the market,” he says.

Guo is now exploring whether other additives could make the carbon capture process even more efficient by speeding up CO₂ absorption rates.

Journal Reference:

Guo, Y., Hatton, T.A., ‘Enhancing continuous-flow CO₂ capture and release from aqueous carbonates via thermal pH regulation’, Nature Chemical Engineering (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s44286-025-00313-8

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Anne Trafton | Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

Polar bears may be adapting to survive warmer climates, says study

The study by scientists at the University of East Anglia (UEA) discovered that some genes related to heat-stress, aging and metabolism are behaving differently in polar bears living in southeastern Greenland, suggesting they might be adjusting to their warmer conditions.

The finding suggests that these genes play a key role in how different polar bear populations are adapting or evolving in response to their changing local climates and diets.

The authors say understanding these genetic changes is important for guiding future conservation efforts and analysis, enabling us to see how polar bears might survive in a warming world and which populations are most at risk.

It comes as over two-thirds of polar bears are predicted to be extinct by 2050, with total extinction expected by the end of this century. The Arctic Ocean is also at its warmest with temperatures continuing to rise, reducing vital sea ice platforms that the bears use to hunt seals, leading to isolation and food scarcity.

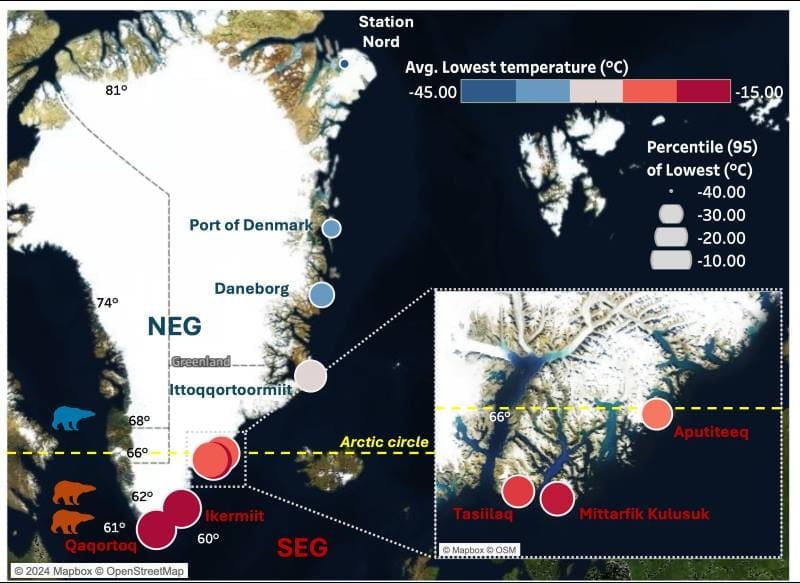

The study, published in the journal Mobile DNA, analysed blood samples taken from polar bears in northeastern and southeastern Greenland to compare the activity of so-called ‘jumping genes’ - small, mobile pieces of the genome that can influence how other genes work – their relationship with temperatures in the two regions and associated changes in gene expression.

The scientists found that temperatures in northeastern Greenland were colder and less variable, while in the south-east they fluctuated and it was a significantly warmer, less-icy environment, creating many challenges and changes to the habitat there, and one similar to future conditions predicted for the species.

Lead researcher Dr Alice Godden, from UEA’s School of Biological Sciences, cautioned that while the finding offers some “hope” for the polar bears, efforts to limit global temperature increases must continue.

“DNA is the instruction book inside every cell, guiding how an organism grows and develops,” she said. “By comparing these bears’ active genes to local climate data, we found that rising temperatures appear to be driving a dramatic increase in the activity of jumping genes within the southeastern Greenland bears’ DNA.

“Essentially this means that different groups of bears are having different sections of their DNA changed at different rates, and this activity seems linked to their specific environment and climate.

“This finding is important because it shows, for the first time, that a unique group of polar bears in the warmest part of Greenland are using ‘jumping genes’ to rapidly rewrite their own DNA, which might be a desperate survival mechanism against melting sea ice.”

Dr Godden added: “As the rest of the species faces extinction, these specific bears provide a genetic blueprint for how polar bears might be able to adapt quickly to climate change, making their unique genetic code a vital focus for conservation efforts.

“However, we cannot be complacent, this offers some hope but does not mean that polar bears are at any less risk of extinction. We still need to be doing everything we can to reduce global carbon emissions and slow temperature increases.”

Over time our DNA sequence can change and evolve, but environmental stress, such as warmer climates, can accelerate this process. This study is thought to be the first time a statistically significant link has been found between rising temperatures and changing DNA in a wild mammal species.

Changes were also found in gene expression areas of DNA linked to fat processing, which is important when food is scarce and could mean the southeastern bears are slowly adapting to the rougher plant-based diets that can be found in the warmer regions, compared to the mainly fatty, seal-based diets of the northern populations.

“We identified several genetic hotspots where these jumping genes were highly active, with some located in the protein-coding regions of the genome, suggesting that the bears are undergoing rapid, fundamental genetic changes as they adapt to their disappearing sea ice habitat,” said Dr Godden.

The work builds on a previous study by the University of Washington, which discovered the southeastern population of Greenland polar bears was genetically different to the northeastern group, after becoming separated about 200 years ago.

Dr Godden and her colleagues analysed genetic activity data collected for that study from 17 adult polar bears – 12 from northeastern and five from southeastern Greenland.

They used a technique called RNA sequencing to look at RNA expression, the molecules that act like messengers, showing which genes are active. This gave them a detailed picture of gene activity, including the behaviour of jumping genes.

Dr Godden said the next step would be to look at other polar bear populations – there are some 20 sub-populations around the world – adding: “I also hope this work will highlight the urgent need to analyse the genomes of this precious and enigmatic species before it is too late.”

Journal Reference:

Godden, A.M., Rix, B.T. & Immler, S., ‘Diverging transposon activity among polar bear sub-populations inhabiting different climate zones’, Mobile DNA 16, 47 (2025). DOI: 10.1186/s13100-025-00387-4

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of East Anglia (UEA)

Canadian wildfire smoke worsened pediatric asthma in US Northeast: UVM study

New research from the University of Vermont reveals exposure to smoke from Canadian wildfires in the summer of 2023 led to worsening asthma symptoms in children in Vermont and upstate New York.

The study, published in the journal Environmental Health, is the first to examine the relationship between wildfire smoke and asthma in the Northeast – which in recent years has seen a marked increase in poor air quality days due to wildfires.

“In 2023 when we couldn’t see New York across the lake, a lot of Vermonters began to worry about wildfire smoke,” says Anna Maassel, a Ph.D. candidate at the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources, graduate fellow at the Gund Institute for Environment, and lead author of the paper. “A lot of people think of Vermont as a relatively safe place to live when it comes to climate change, but we found that smoke coming from hundreds of miles away affected children here.”

Wildfire smoke contains tiny particles known as PM₂.₅, along with other toxic pollutants that can damage the lungs and worsen respiratory conditions such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Nationwide, 6.5% of children and 8% of adults have asthma. Vermont’s rates are higher with 7% of children and 11% of adults diagnosed with the disease.

To assess if wildfire smoke from 2023 affected children in the area, the researchers accessed electronic health records for about 900 youth, ages 3-21, who were receiving treatment for asthma in Vermont and upstate New York through University of Vermont Health.

The team analyzed three different clinical measures that assess how well-controlled a patient’s asthma is for the summers of 2022-2024. Then, they overlaid air quality data onto the region and estimated smoke exposure within each zip code.

Compared with the relatively smoke-free summer of 2022, children’s asthma was significantly less controlled during the smoke-heavy summer of 2023, when plumes from Quebec blanketed the region.

“In the summer of 2023, my pediatric pulmonology team received a high volume of phone calls from concerned parents saying, ‘My child is having trouble with asthma symptoms,” says Dr. Keith Robinson, a pediatric lung doctor at Golisano Children’s Hospital at UVM and co-author of the paper.

The researchers didn’t find the same signal when they compared 2023 with 2024, which was surprising, and the team hopes future research could shed light on why. Still, Robinson says it’s clear that wildfire smoke is affecting Vermont’s youth.

“I think our findings suggest that there is potential for wildfire smoke, even hundreds of miles away, to impact a child’s health,” he says.

Across the country, pollution from wildfire smoke is increasing. A study published earlier this year estimated climate change is projected to exacerbate the problem, leading to roughly 70,000 premature deaths each year by 2050. Without action, wildfire smoke could become one of the country’s worst climate disasters, the authors write.

Robinson says there are steps clinicians can take to help families reduce exposure to wildfire smoke, including closing windows, avoiding outdoor activities and using air purifiers when air quality is poor.

“Clinicians need to make sure that parents and patients understand how to check for air quality, especially when there are wildfires in the area,” he says. “We also need to make sure that patients and families who do not have the means to mitigate the effects of wildfire smoke have support from public health agencies.”

The study was funded by UVM’s Planetary Health Initiative and brought researchers together from across UVM, the Robert Larner M.D. College of Medicine and UVM Health.

“When you’re able to work with researchers that have a different area of expertise, it brings the impact to another level. Personally, I learned a lot from my teammates about climate change and environmental health. This project demonstrates the impact of collaboration across UVM departments,” Robinson said.

The research also reflects the university’s commitment to Vermont.

“This study is another example of how UVM researchers can engage with our state and our region to connect the dots between climate change and human health,” said Taylor Ricketts, director of UVM’s Gund Institute for Environment and co-author of the paper. “Understanding emerging threats to children’s health is a first step toward anticipating and reducing them.”

The research team also included: Paige Brochu, a research assistant professor in the Rubenstein School, director of UVM’s Spatial Analysis Laboratory and a Gund Institute affiliate; Valerie Harder, with the Vermont Child Health Improvement Program and a professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the Larner College of Medicine; and Dr. Stephen Teach, a pediatric emergency medicine physician at University of Vermont Health and the Larner College of Medicine.

Journal Reference:

Maassel, A.K., Brochu, P., Harder, V.S. et al., ‘Wildfire smoke and pediatric asthma control in the Northeastern United States: a cross-sectional study’, Environmental Health 24, 91 (2025). DOI: 10.1186/s12940-025-01245-9

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Brittany Patterson | University of Vermont (UVM)

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay